Sign at a Chicago South Side Catholic school:

JESUS LIVES!

REPORT CARD PICKUP

(The unwritten next line must be, “SAY YOUR PRAYERS.”)

Sign at a Chicago South Side Catholic school:

JESUS LIVES!

REPORT CARD PICKUP

(The unwritten next line must be, “SAY YOUR PRAYERS.”)

Toujours Provence by Peter Mayle. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991. 260 pages.

Having survived French bureaucracy, endless home improvement, goat races, hunters, Massot’s dogs, summer visitors, and other hazards during A Year in Provence, Peter Mayle brings us more of the same in Toujours Provence.

This time Mayle takes a more illustrative approach. Beginning with a pharmaceuticals marketing brochure that depicts a snail whose “horns drooped” and whose “eye was lackluster,” Mayle educates us about health concerns and approaches in Provence — including house calls. Anecdotes relate Mayle’s love of picnicking Provence style (with chef, wait staff, and linens); his quest for singing toads, truffles, and napoléons (the coins); his pursuit of Pavarotti and pastis; and, of course, his passion for the region’s fresh foods and fine vintages.

With a few exceptions, such as the history of pastis and the more sobering story of summer drought and forest fires, much of Toujours Provence will seem familiar territory to readers of the first book. For the most part, Mayle is in fine form, writing that Bennett, “looking like the reconnaissance scout from a Long Range Desert Group . . . had crossed enemy lines on the main N100 road, successfully invaded Ménerbes, and was now ready for the final push into the mountains.” Some anecdotes, like “No Spitting in the Châteauneuf-du-Pape,” end brilliantly, while others, such as “Napoléons at the Bottom of the Garden,” fall a little flat.

Judith Clancy’s delightful artwork is back, but what is missing from Toujours Provence are the quirky characters we came to love or at least wonder about. Most are mentioned or make a brief appearance, but mainly they are relegated to the background. Even Mayle’s neighbor Massot (“. . . it would be difficult to imagine a more untrustworthy old rogue this side of the bars of Marseille prison”), to whom half a chapter is devoted, is here more caricature than character. We know no more about him, or Faustin and Henriette or Monsieur Menicucci, than we did at the end of the first book. By now, Mayle’s circle has expanded , but no one he meets, from the toad choir director to the flic, is nearly as interesting as his neighbors or his builders from the first book.

Like an adequate movie sequel, Toujours Provence carries on in the same vein as its predecessor, with a slightly different or reduced cast and a little less originality and wit. Perhaps more appropriately, I should say it’s like a wine slightly past its peak — still worth drinking, but somehow not quite as enjoyable.

28 April 2008

Copyright © Diane L. Schirf

Cousin Phillis by Elizabeth Gaskell. London: Hesperus Press, 2007. 144 pages.

Like Cranford and Wives and Daughters, Cousin Phillis is a variation on the themes that seemed to have preoccupied Elizabeth Gaskell: the changes wrought by mechanization and the different spheres in which men and women live and operate.

When the narrator, then 19, meets Phillis, her physical world is small, contained, and regular, predictably following the seasons as agricultural life does. Her intellectual life, however, is vast. She is comfortable with Latin and the principles of mechanics; she attempts to read Dante in Italian. As Jenny Uglow notes in the foreword, “. . . she does not crave ‘independence,’ but connection . . . She yearns to use her mind and give her heart.” She wants to be a woman.

By contrast, the men around her are reshaping the world with their thought, their inventions, their ambition, and their work. Even the narrator, who admittedly lacks his father’s inventive genius and Holdsworth’s drive, is doing more than Phillis ever could simply by serving as Holdsworth’s assistant.

With her flourishing intellectual curiosity and her growing sexual awareness, it’s natural for Phillis to discard the pinafore that represents the restrictions placed on the Victorian woman-child and to desire a man whose tastes, abilities, and drive seem to parallel her own. The result is not surprising. As a woman, her opportunities are limited, while those of the man stretch across two continents and grow greater with each rail laid. It’s clear who is destined to be disappointed.

As with the other novels, Gaskell captures a world within her own memory that in many ways had already ceased to exist. The narrator, older and married now, recalls in vivid detail an experience colored by the passage of time and by the changes that have transpired. The bogs, “all over with myrtle and soft moss,” could not fail to be altered irrevocably by the railway line, nor could the Hope Farm, with its cozy “house place” and “the clock on the house-stairs perpetually clicking out the passage of the moments.” Phillis’s father learns that she cannot be kept in a pinafore and all that it represents, and the narrator “feared that she would never be what she had been before.” No one is.

The narrator leaves us with enticing mysteries. What has prompted him to write about Phillis? What has happened? What does he want to accomplish by telling her story now? What is he trying to recapture? What happened to Phillis? What happened to the Hope Farm and its way of life that he so beautifully recalls and the tenor of which is so effectually altered by events?

Cousin Phillis is a tiny treasure — always evocative, never overwrought. We see Phillis and her natural evolution from child to woman with the narrator’s wisdom of maturity and the clarifying, yet softening filters of time. The narrator — and Gaskell — leave Phillis trapped in time, changed, newly aware of the broadness of her desires and of the obstacles she faces, and determined to “go back to the peace of the old days” — a hope that is nearly impossible to achieve. There is no going back, as Phillis must surely know.

27 April 2008

Copyright © Diane L. Schirf

Warning: Women’s matters mentioned.

For at least 14 days I’ve had symptoms of PMS. My period was due to start about April 24 (which meant that I had to cancel my first appointment with a different gynecologist for the 25th). At around 11 p.m., there were signs that it was starting. Those signs continued for almost 60 hours in combination with the PMS, making me doubly miserable. At last, it looks like it means business.

This happened last month, when my period dropped hints that it was on its way and then arrived unapologetically late. I don’t like to contemplate this, but even I can’t deny that this is probably the beginning of the end — perimenopause. I don’t feel like a crone, and I’m not ready to be one.

Billions of women have undergone this rite of passage, but what I’m starting to understand is that it’s going to be unpleasant — not because of the discomfort, which can be considerable, or the changes, which can be dramatic, but because my body is doing these things behind my back and without my permission.

Perimenopause and menopause are inevitable for women who live long enough, but I don’t see how you can prepare for it, any more than you could for puberty. If the one marks the beginning of the entry into adulthood, the other marks the beginning of the end. As an animal, my useful (reproductive) life is over. Logic can’t always overcome the underlying finality and sadness of that simple truth.

Yesterday J. decided to stop by on his way to work to take a walk with me (part of his determination to be more active), but while driving he talked himself out of working. I was waiting for him with tea in an insulated cup so we could combine activity with something comforting.

In spite of the darkness (the lights were off), we walked around Promontory Point and to the 57th Street underpass. Along the way we spotted four parties with fires blazing in the stone circles. The fires worried me because they were large, and the wind was floating sparks from them everywhere. I half expected to see the Point in ashes this morning. At each fire, J. stopped to contemplate the beauty of the flames and then pointedly reassured me each time that he is not a pyromaniac.

Because he had decided not to go to work, I made him watch Buster Keaton’s The General. It’s a brilliant movie — comedy with a touch of adventure, and chase scenes that have never been equaled. Every obstacle is an example of Keaton’s inventive genius, and every exquisitely timed stunt a testament to his physical prowess. His character’s love interest is played by Marion Mack, who is more than the obligatory eye candy. She turns in a delightful performance that ranges from expressive (when she thinks that her man wasn’t even in the line to enlist) to as stone-faced as Keaton himself as she grimly feeds the General’s boiler with delicate sticks of wood. When Keaton strangles her in frustration, then kisses her violently mid-pursuit, it’s more than a comic bit; it’s an erotic moment that should be remembered as one of cinema’s great kisses — anger turned to passion.

The General is not just a gag-filled chase; through visuals and only a handful of captions, it tells a satisfying story. To me, it’s one of the most nearly perfect movies ever made.

This morning a nightmare woke me up. When I did, I could feel the earth trembling and wondered if there was more shaking going on along the New Madrid fault.

Then I realized the trembling was a sensation caused by the pounding of my terrified heart.

Why do I keep going back to college? What is missing in my intellectual life that makes my sleeping brain feel deprived? Or is it a social life for which I yearn?

I returned to an unfamiliar dormitory and found a long line of people on the stairs leading to the basement, waiting to get into a concert. I looked up; a dry-erase board announced: ZEUS — 1, perhaps with some other cryptic notes. I knew this notation meant that he was alone (no other band members) and performing for one night only. I also knew “Zeus” was Sting from The Police, although at the moment I couldn’t think of the name “Sting.”

I spotted two men in the building who looked familiar. One was unmistakable; he towered over everyone, and his hair was curly. In the dream the other man was familiar, but I could not think of who he might be.

“Are you Gabe?” I said to the tall man, noting that he had not aged at all and wondering if I were in a time warp. He admitted that he was, and I asked him, not at all hopefully, if he recognized me. He didn’t. I was not surprised. I explained how I remembered him and about my repeated attempts to return to college, even after graduating. I asked him if he were attending classes. “No,” he said. “I’m here for a secret project that I can’t tell you about.” Instead of thinking he was there as a scientist, I concluded he must be a psychology researcher working in a dormitory and speculated why this would be secret. I also realized that there was a secret message in “I’ll Be Watching You” that had nothing to do with stalking, but I knew I could not articulate it. I may have tried.

By now I wanted dinner, but the café workers had pulled a chair halfway across the entrance. I did not understand this obvious hint, so a testy middle-aged woman came over to tell me the café was closed and to pull the chair more firmly across the entrance. I thought, Already I am paying for meals I don’t eat. I am irresponsible.

I thought of going somewhere else — the bookstore? another dorm? — but realized now that I was nude. No one earlier had noticed, or maybe I had become suddenly nude. I wanted to leave but to go outside across streets and lawns and through buildings without wearing a top seemed risky.

I started to think about why I was there and the classes I still struggled with. I might never pass or perform to my satisfaction; I might never escape.

Here we have two countries, far apart geographically and culturally — China and the United States.

It’s been reported that, with every wave of Tibetan rebelliousness, the Chinese people grow more impatient with the Tibetans. They were ignorant savages until we gave them civilization! Without China, without us, they’d still be in a technological and cultural dark age. Who are they to question Chinese authority? How dare they? Why can’t they be more like us?

Meanwhile, the rebellious Tibetans think, “Without China, we’d be free.”

Americans in the Boston, Philadelphia, and Chicago of the 1800s who read about the Indian wars in the west undoubtedly had a similar reaction. Those savages! Complaining about the desecration of their hunting grounds and their sacred this and that. Why can’t they live on farms and in towns? Why can’t they be more like us?

I suppose this is natural — we tend to be most comfortable with people just like ourselves. This explains Chinatowns, Little Italies, exclusive country clubs, high school cliques, and team pride. We like who we are, and we secretly wonder why others don’t aspire to be just like us — even when, like the Tibetans and the Indians, they clearly like who they are, too.

That’s why the public’s reaction to the government intervention at the FLDS ranch in Eldorado, Texas, is interesting. Given the unproven allegations of child sexual abuse and the group’s theological beliefs (including polygamy), I didn’t expect much sympathy from the public. Almost everything about FLDS is different — their religion; their dress and manner; and their work, community, and family lives. I expected many Americans to dismiss them as a dangerous cult, a threat to the normal order. Yet many people who are posting online seem sympathetic to them without worrying why they can’t be “more like us.”

Whether we admit it or not, I think part of that is because they have a certain resemblance to the middle class. Their dress may be old-fashioned, but it’s not exotic or foreign. They believe in God, although their theology is unorthodox. They practice polygamy, but so have others before them. Without the sexual abuse charges, they seem more eccentric than menacing.

Of course, it’s also easy to take their side because, unlike the Tibetans and Indians, they aren’t a different ethnic group that happens to have land and resources that the rest of us want. This makes it much easier for the man and woman on the street to feel for them.

I would like to think that part of it, too, is post-911 privacy and rights usurpation backlash. For years the U.S. government has taken advantage of our fears to insinuate itself into our lives and to ferret out our information — even data on the books we read and buy. At last there may be a sense that the government has gone too far, that George Orwell was only a couple of decades and a few details off. If hundreds of children can be taken from their mothers based on one unproven allegation made by phone by someone who can’t be found, what could happen to you or me and our families?

Like the Tibetans, like the Indians, we are not Borg. We will not be assimilated. Resistance is not futile in the land of the free and the home of the brave.

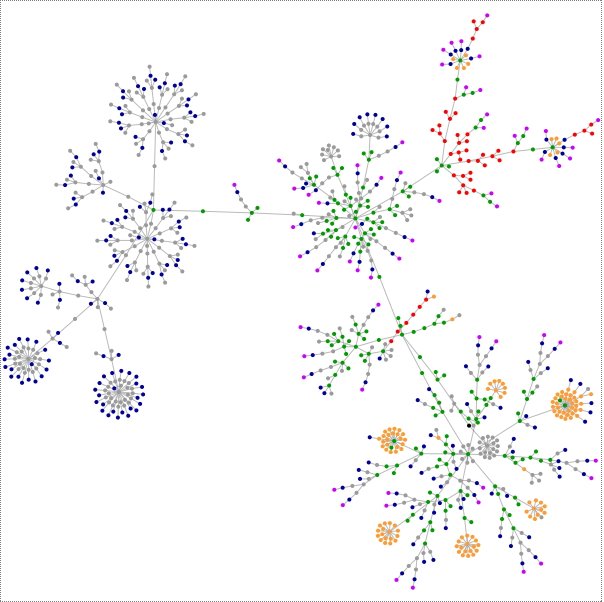

Here’s my journal as a graph courtesy of the defunct Web sites as graphs.

What do the colors mean?

blue: for links (the A tag)

red: for tables (TABLE, TR and TD tags)

green: for the DIV tag

violet: for images (the IMG tag)

yellow: for forms (FORM, INPUT, TEXTAREA, SELECT and OPTION tags)

orange: for linebreaks and blockquotes (BR, P, and BLOCKQUOTE tags)

black: the HTML tag, the root node

gray: all other tags

People here seem to feel it’s been a long, cold, lonely winter. I’m tired mostly of bundling up, the constraint of heavy clothes and a coat, and still feeling cold when walking about at night. Until this week, a few moments that felt like spring yielded to more winter wind and cold.

Inevitable every year, spring is being persistent, manifesting itself through manmade and natural signs.

Pregnant women. Years ago someone pointed out to me that, in spring, the world is full of pregnant women. Until then, I had not thought much about this, but, judging by the number of protruding bellies I’ve seen in the past few weeks the long, cold, lonely winter was not all that lonely for many.

Garden kitsch. In the seasonal products aisle of Walgreens, a frog chirped as I walked by. After every fourth chirp (two sets of two chirps apiece), his mutant pink tongue rolled out enticingly (or threateningly). As mankind displaces wildlife like frogs, the unspoken answer seems to be to replace the live creatures with mechanical plastic replicas.

Little brown jobs. While walking through The Flamingo garden, I startled what birders know as a little brown job (LBJ). Just as I realized that it was not one of the ubiquitous European house sparrows but one of the many interesting migrants of the Central Flyway, it flew off. Nuts.

Love is in the air. In J.’s neighbor’s back yard, a male grackle fanned his tail seductively and performed a rudimentary dance that clearly said, “Look at me! Look at me! Aren’t I handsome?” The female must have been duly impressed because an activity ensued that was definitely not suitable for children or more sensitive viewers. I don’t know about bees, but this pair explained why birds were singled out as an example.

The Flamingo pool. The cover has been removed, the winter meltwater drained, and the muck mopped out. Painting should be next. The pink-and-white deck chairs are piled up and waiting.

Come sail away. A few hardy sailors took their boats out Sunday, undoubtedly determined to pretend that it was a warm spring day, despite the chill and wind.

Garden goods. J. called me from a nursery; he is feeling the call of the perennials.

Puppet Bike. My favorite Chicago attraction is back on the street.

Insects and spiders. An insect parked itself on my window the other day for several hours, perhaps thinking it was a pickup joint. The spider brigade that uses my windows as a full-service hotel (with restaurant) has not reappeared, but Hodge and I do find individual members of the advance guard checking out the indoor comforts.

Increased workload. In the winter, when I dread bundling up and facing the cold and could put in extra time, my workload is lighter. The moment it’s warm and light enough in the evenings to enjoy the outdoors, suddenly pent-up projects are found to keep me busy after hours.

That’s all I can think of for now. I can’t wait for the sighting of the first butterfly.

J. called me unexpectedly Saturday with an idea. Last year we’d talked about being more active on our outings, and he’d found something outdoors that interested him — he’d seen an announcement that the toboggan run at Swallow Cliff Woods is to be torn down. Although he never used it, he remembers the run from his childhood and wanted to see it again.

The tearing down of many old buildings in his area upsets J. I understand why, although I point out to him that people are free to do what they like with their property, and nostalgic is not equivalent to historic. Unless a Civil War sniper used the run’s tower as a base to influence a battle outcome, or Abraham Lincoln slept there, it’s just a toboggan run. Even the town in which Swallow Cliff Woods is located can’t save it. I’m sure much of what I loved best about Western New York of the 1960s is gone. I take some comfort in knowing that nothing but time, age, or disease can rob me of my memories.

During the drive, I was reminded of why the south suburbs have grown on me — they are not yet overdeveloped. That this will happen is inevitable, and the signs are there, like a bulldozed field and a developer’s sign across the road from a farmhouse and barn. On the other hand, the Forest Preserve District of Cook County Web site claims that it owns 67,800 acres, or 11 percent of the land in Cook County. Much of that space, like Swallow Cliff Woods, are in the south and southwest suburbs.

It had rained earlier, the sky was overcast, and there was very little spring green in evidence, but for me it’s lovely to be in the woods at any season.

Of course, to get to the woods you must climb the stairs up the hill to the top of the toboggan run. My left knee hated it, my lower back agreed with my knee, and my cardiovascular system let me know that it hadn’t been prepared properly. I took several breathers even as older people passed me. J. beat me to the top and documented my labors in photographs. He wondered about the haul down later; I told him that the descent would be easy.

At the top we spoke to a couple who are about our age. The man recalled using the run as a child in the 1960s, and the quickness and terror of the initial drop. Still panting, I thought about how thousands of children must have climbed the steps effortlessly, over and over.

The man said the reason given for the destruction is cost, although he seemed skeptical. His wife, more practical, pointed out that the Forest Preserve District probably pays expensive insurance premiums. This observation didn’t mollify the men, but they didn’t dispute it. We also discussed the unpredictability of employment, as snow is very irregular in this area.

As we talked, a number of people walked up the steps; a few made repeat trips. We had noticed piles of pebbles and rocks on the stone ledges; the man explained that regulars use the stairs for exercise and track the cumulative number of trips with these rocks. He said that he and his wife are among these regulars, sometimes making five round trips, sometimes three. Often they bring their dog, who is “more interested in the woods than in the stairs. Can’t imagine why.” Later, as we were descending, we observed a determined man with nearly white hair make two round trips without showing any signs of tiring or quitting.

We had some time before sunset, so we walked one-quarter to one-half mile down a wide trail in the woods — wide enough for the horses whose droppings we stepped around. At one point, I heard a dense chorus of chirps that didn’t sound quite like birds or insects; it may have come from frogs, although I don’t know. Alas, I’ve never had much opportunity to develop my woodcraft skills.

During the return, the woods seemed quieter except for the regular roar of jets on their final descent into Midway Airport. In the relative silence, we heard the very loud drilling of a somewhat distant woodpecker. It’s a sound that never fails to thrill me.

J. spotted a tree next to the trail that had two thin trunks of a different bark growing around it. These trunks, which seemed to have clumps of “hair,” looked parasitic to my uneducated eye. I had a strangely emotional reaction to them, a primitive one of horror, as though I were seeing more than a woody plant (or parasite) embracing (or strangling) a tree. I shuddered inwardly while J. took photos for reference in case I wanted to figure out what it is.

In the car while we were debating where to eat, I spotted a sign about a “Lake Katherine Nature Center and Botanic Gardens.” J. backtracked a bit. We walked around this area in the dusk light, observing mallards and a lone swan, probably a trumpeter.

From the neatness of its shores, I judged Lake Katherine to be manmade. The lake, fed by miniature waterfalls, and the surrounding nature preserve consists of 125 acres that began with open space reclaimed by Palos Heights in 1985.

Near the waterfalls, J. noted a sign warning against going onto the little island midstream, which is inhabited by northern watersnakes. While these snakes are not venomous, according to the sign their bite can cause significant bleeding. As if that were not enough to deter the more macho and determined adventurers, the sign writer added that disturbed watersnakes will poop and vomit. J. knew that the triple threat of blood loss and snake poop and vomit was not enough to stop me, but the growing darkness and the unsure footing on small, slippery rocks in the water were. I leaned forward for a while and peered into the misty dimness, willing northern watersnakes to appear. They didn’t.

A peaceful place, Lake Katherine and its grounds are marred only by the electric towers that loom against the southern sky. In the fading light, with mist rising thickly from the water’s surface, I could try to imagine the towers and all that they represent away.

We undid any benefits conferred by the exercise by eating at an Italian family restaurant, beginning with onion rings (my strange craving) and a combination plate of mushrooms and mozzarella and zucchini sticks, a Blue Moon Belgian White and fetuccine alfredo for me, and a soft drink and tortellini for J.

Stuffed (and carrying lots of leftovers), we came here, drank coffee infused with blueberries, and pretended not to ache.