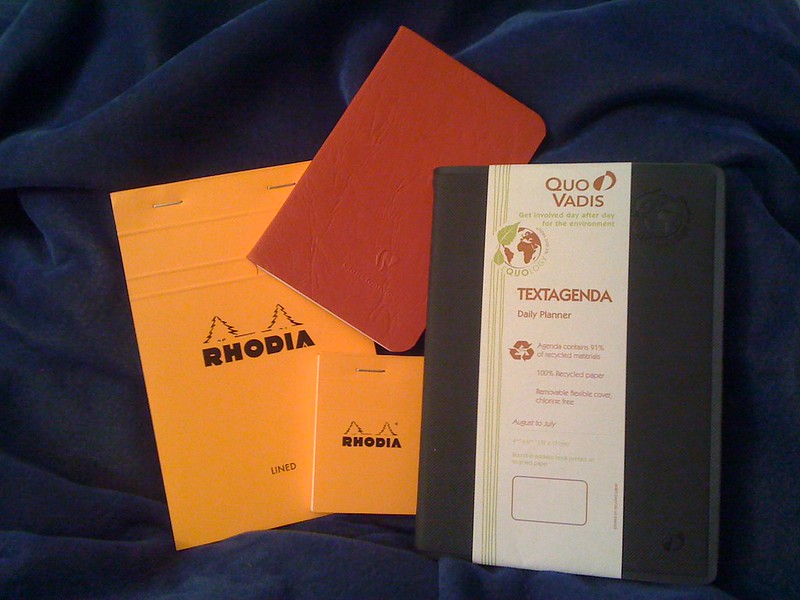

I found a Quo Vadis Textagenda daily planner, a Rhodia No. 14 pad, a teeny Rhodia No. 10 pad (I’d heard of it, but assumed it was a myth), and a gorgeous Clairefontaine notebook with a textured red cover, all courtesy of Exaclair, Inc. Vice President of Marketing Karen Doherty. Although I’m not an expert, and I’m also terrible at keeping a schedule, I’m going to break the Textagenda in at work over the next couple of weeks and write a review. Stay tuned.

Monthly Archives: September 2009

Life at street level

Saturday, September 19, I invited J. over for an end-of-summer dip in the pool. It’s been a cool, cloudy September, and with the neighborhood urchins back in school only a few hardy residents have been coming out to do a few laps. The sun, sinking toward the south, now hides behind the building most of the day, so there’s nothing for sunbathers to bask in. The pool, once crowded and noisy, is empty and quiet now.

The pool’s water is warm, but the breeze can be nippy on wet skin. J. finds it hard to get into the water, so he lowers himself slowly, while I start to shiver and my teeth to chatter when I get out and the air hits me. I noticed that a young woman who jumped in for a few laps scurried inside after a brief rub with a towel. There’s no drying off naturally at sunset when the 65-degree Fahrenheit air is blowing.

Dried off and warmed up, we decided to eat before J. continued on to work. He mentioned Western Avenue, which seemed too far to me under what felt like time and energy constraints. We settled on Calypso Café — not his idea of new and adventurous, but at least we hadn’t been there in a while, and the menu is pretty varied.

This trip also gave me a chance to see what was left of Dixie Kitchen and Bait Shop — which is nothing, just a very clean excavation, with no sign of construction that I could tell. Ostensibly, a clean site presents a better picture to potential investors than a doomed building, although I wonder who’s buying or lending right now. As I told J., it looks to me like the University of Chicago wanted to flex its muscle and show the neighborhood it means business.

To me, this raises the question of what business the university is in, exactly. Given the number of times they contact me by phone, e-mail, and mail to plead for funding, I would think they’re focusing on their core mission, which I think would be education, research, and medicine. On the side, however, they can’t seem to resist the real estate business — owning and managing the local shopping center, buying property and providing vague explanations, and now buying and redeveloping the old Harper Court.

J. asked me if other big universities carry so much weight in their neighborhoods. To his surprise, I laughed. The University of Chicago is a flea compared to, say, the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

I like Ann Arbor. From the bed and breakfast where I stay, I can walk to countless local boutiques and shops, like Peaceable Kingdom and the People’s Food Co-op and Café Verde. For those students who require their suburban comforts, Borders and Starbucks are right off the main campus. But my favorite, even now that many of the brick streets have been paved over, is Kerrytown, a quaint and quirky shopping center where you can find so much variety at the shops or the frequent farmers’ market. At Kerrytown, I feel like I’m in a small village artisans’ market — something that the “college town” of Hyde Park sorely lacks. So much here is spread out and is purely utilitarian; many of the limited storefronts are dedicated to salons, dry cleaners, locksmiths, optometrists, dentists, and the like. A great boutique like Parker’s Pets (akin to Kerrytown’s Dogma and Catmantoo) is isolated on a boulevard, away from other shops in an area that has little to draw pedestrians. Open Produce and The Fair Trader are also wonderful additions to the area, but they’re far from the heart of the university, and students and staff would have to go out of the way to shop there — with little else nearby to browse except a dollar store.

Now imagine Parker’s Pets, Freehling Pot and Pan Company, Bonjour Bakery and Café, Toys Etcetera, The Fair Trader, Istria Café, and Open Produce all on one or two blocks. Throw in a movie theater and even a small venue for folk and world music nearby, and you’ve pictured downtown Ann Arbor. If the university is going to micromanage Hyde Park, can’t they come up with a master strategy and vision that’s as conducive to community and participation as Ann Arbor? Even the 55th Street side of the Hyde Park Shopping Center, with its landscaped courtyard and arts, garden, and book fairs, is a step in the right direction.

My understanding is that a mixed-use high-rise is planned to dominate Harper Court. Perhaps density is ecologically “green” and the best use of urban space. I’ve noticed, though, that high-rises don’t foster community in the way that clustered storefronts and courtyards do. Imposing and bulky, often with little open space, high-rises seem distanced from their surroundings. They don’t entice the neighborhood to gather. Much of urban social life happens at street level, spilling out from restaurants, pubs, taverns, cafés, shops, and three flats, not from high-rise hulks.

Nowhere in Chicago is this more evident than in Lincoln Park, where the main streets like Lincoln and Clark, Armitage and Diversey, are filled with people shopping, eating, drinking, and hanging out in front of the most popular places.

By contrast, the primary commercial street near the University of Chicago is 53rd Street, where many of the most interesting shops (including those that were once in Harper Court) have disappeared, including, for example, the Chalet (replaced by a chain) and the import store (owner retired and moved). Because of the proximity of Kenwood Academy and for other reasons, the police discourage loitering, so what makes Lincoln Park sociable, popular, and successful is considered a threat in Hyde Park. Even men playing chess are dangerous, at least according to those who had the chess tables at Harper Court removed years ago, driving the rowdy players over to Borders and Harold Washington Park, where they continue to disturb the peace with their intent stares at chess pieces.

I’d be happy to be wrong, but unless the street level of a high-rise complex is engaging in design and offers something for many, the university’s plans don’t seem to add all that much to the development of community except a modern face. Unless there’s something really compelling at that level, I suspect most of us will still be at the park watching the chess players, at Promontory Point soaking up rays, or indulging in a croissant at Bonjour, and still wishing there were some place to go and some place to hang out in Hyde Park.

Dream: This is no place like home

I was at a party given by my parents, but the trailer was nothing like it used to be. The rooms were dark and different, as though they had been rebuilt within a different shell. The main room now sported an impossible cathedral ceiling that made it feel oppressive instead of open and airy. My closet, although full of scattered boxes, was much bigger than my bedroom and was covered with black paper. Despite its crammed space, it had become the focal point of the party.

I saw my dad from behind, staggering as though he were drunk. As he never drank, I suspected he was gravely ill and tried to catch up to him to help him, but he somehow kept eluding me like an illusion.

Something was terribly wrong with my world, and I was frightened.

Book review: Mary Barton: A Tale of Manchester Life

Mary Barton: A Tale of Manchester Life by Elizabeth Gaskell. Edited with an introduction and notes by Shirley Foster. New York: Oxford University Press. 2006. 480 pages.

A tale of Manchester working life set in the 1830s, Mary Barton begins as bucolically as any gritty urban novel can. The Bartons, who are expecting an addition to the family, meet the Wilsons, who are carrying their infant twins, at Green Heys Fields. The charm of these low, flat, treeless tracts lies in their rural contrast to “the busy, bustling manufacturing town [he] left but half an hour ago.” The couples adjourn to the Barton home for tea, where Gaskell lovingly describes every modest luxury such working folk can manage — the bright green japanned tea tray with its scarlet lovers, the cupboard of crockery and glass of which Mrs. Barton is so proud, and the hodgepodge of furniture (“sure sign of good times among the mills”). In honor of their guests, the Bartons send young Mary out for fresh eggs (“one a-piece, that will be five pence”), milk, bread, and Cumberland ham.

Thus Mary Barton commences with a self-conscious air of cautious prosperity, but underneath the pleasure of the occasion are hints of despair to come — Mrs. Barton’s distress over the disappearance of her sister, and the Wilsons’ “little, feeble twins, inheriting the frail appearance of their mother.” In chapters I and II, Gaskell sets up the end of abundance and joy for the Bartons and the beginning of misery for their entire class in the mill city of Manchester.

Mary Barton is a novel of contrasts. While the Bartons take homely pride in their furniture and wares, the Carsons live in a “good house . . . furnished with disregard to expense . . . [with] much taste shown, and many articles chosen for their beauty and elegance.” As Carson’s former employee, Ben Davenport, lies dying in a filthy basement in the company of his wife and children, who are “too young to work, but not too young to be cold and hungry,” Carson’s youngest daughter Amy tells her brother and father that she “can’t live without flowers and scents” and that “life was not worth having without flowers.” They can’t live without food and shelter, and she thinks she can’t live without luxuries. Perhaps the most terrible contrast is between the “listless, sleepy” Carson sisters and the tragedy that interrupts their idle chatter.

The contrast and conflict between the rich and the poor, the men and the masters, is not conventionally based on envy or even class; Carson was once no better and no richer than anyone else. The men don’t aspire to wealth, at least for now. They want to feed their families and perhaps to enjoy the simple comforts the Bartons once shared with the Wilsons. What keeps masters and men apart is not class or money, but a more fundamental unwillingness to acknowledge the other’s humanity. Mr. Carson can’t be bothered to recall who Ben Davenport is, other than one of the many faceless men who worked for him for many years, or to give Wilson more than a useless outpatient order. Instead of approaching the masters, the men, who are powerless as individuals, join groups and send delegates like John Barton to London and Glasgow to try to gain government support for their cause. On their own, they fail.

Neither side is willing to break the communication barrier. Ignoring one of their number who wisely notes, “I don’t see how our interests can be separated,” the masters choose to hide the conundrum they face from the men, who are described as “cruel brutes . . . more like wild beasts than human beings.” Even as the omniscient narrator shows the just causes for both groups’ anger toward one another and tries to avoid demonstrating a preference, she can’t resist retorting parenthetically, “Well, who might have made them [the men] different?” It takes a murder and a near miscarriage of justice merely to open the door to redemption for the man in each side’s leading role.

Mary becomes the fulcrum of the characters and plot, connecting the Bartons to the Carsons, the unforgiving John to the repentant Esther, the worldly men and the more spiritually minded women. Through positive and negative models like Alice, Job, Margaret, Esther, Mrs. Wilson, and Sally, and through her true and patient if frustrated lover, Mary avoids Esther’s fate and is transformed from a heedless young girl into a courageous woman who is able to withstand the pull of her divided loyalties.

Confronted with the undeniable humanity of John Barton and the relentlessness of his unfamiliar poverty, Mr. Carson finally recognizes the need for change. As guardian of the old institutions, however, he struggles with his ambivalence toward taking action. Meanwhile, Mary Barton simply leaves the dead and the past behind to embrace an entirely different kind of future in a new country.

Mary Barton lacks some of the psychological depth and nuances that make Gaskell’s Wives and Daughters more interesting and engaging; here, the characters behave consistently and predictably. Despite the ease of its characterizations and assumptions, though, Mary Barton is a surprisingly stark, unvarnished look at the poorer, seamier side of urban industrial life. Gaskell accomplishes what the masters and men have failed to do — she recognizes the humanity in each of them and hints at its potential if only it is discovered and embraced.

16 September 2009

Copyright © Diane L. Schirf

Planet Saver Sack

A lot of the people at Blick Art and Argo Tea have complimented me on this “Planet Saver Sack,” a gift from J. They probably wonder how such a frumpy old woman got hold of such a cool bag. I wasn’t sure about it at first, but now that I’ve seen the series I’m thinking I should buy at least one more.

Dream: Weird physics

I was in a strange house with my brother and other people. Nothing was right, within or without. The flows of time and space felt wrong, and the end seemed to be drawing near.

When I saw a vase perched at a right angle to the floor of the fireplace, I had an epiphany — the answer lay in physics. I became even more downcast, however — I know nothing of physics.

I thought of a child named Liu, who I knew could help. But how to find him in this strange house, immersed in fluid and darkness?

Please Mr. Postman (the blue U.S. mailbox)

At times separated by an ocean or by hundreds of miles, John and Abigail Adams wrote thousands of letters to each other, covering personal matters such as their farm, family, health, and hopes, as well as their views of freedom, the American Revolution and government, and its participants. Despite the distance, quite possibly their correspondence benefited from postal efficiencies introduced by fellow revolutionary and occasional nemesis Benjamin Franklin, who was appointed Joint Postmaster General of the colonies for the Crown in 1753 and Postmaster for the United Colonies in 1775.

Adams wrote prodigious numbers of letters throughout his adult life, to Abigail, children and grandchildren, and friends on both sides of the Atlantic. Through letters, he and Thomas Jefferson, past their primes and their ambitions, rekindled their friendship and their dialogue about the rights of man and the role of government. Adams finally quit writing in extreme old age, when his eyes were nearly sightless and his hands shook too much to manage a pen. Only physical infirmity deterred him.

As revolutionaries, then as president and president’s wife, John and Abigail had a great deal to say. Like Benjamin Franklin, they were keenly aware that what they wrote would become part of U.S. history.

I happened to be reading John Adams by David McCullough when I saw the Washington Post story about vanishing blue U.S. mailboxes that had become a fixture on city street corners and in the downtown area of many a burg. With e-mail, texting, social media like Facebook and Twitter, 24/7 mobile phone access, and other instant, on-the-go ways to communicate, who today takes the time and effort to write letters? Many seem to be able to communicate what we have to say in Twitter’s 140 characters (even John Quincy Adams), except when we’re texting cryptic messages back and forth: “whr ru?” “*bcks.” “b thr sn.” If you feel you need to communicate at greater length, you might start a blog, which, without a theme of general interest to the world or of particular interest to a special niche, will probably quickly fizzle out from lack of participation on both ends, readers’ and writer’s. Of course, you might not want to say to the world what you would to family, or to family what you would say to friends.

Although she did not have much to say, my mother wrote letters to sisters and brothers spread out across the country — Pennsylvania, Arizona, California. She didn’t like writing letters. I don’t think any of them did, because letters she wrote and received invariably began with an apology that the writer had not written sooner, followed by numerous apologies for having nothing to say, descriptions of the local weather, a bit of news if there were any, e.g., “Diane starts school in two weeks, Where did summer go?” Why write when there was so little to say and it was such a disliked chore? The answer — long distance was relatively expensive and reserved for truly important and immediate news, like deaths. Usually only one aunt, more affluent and urbanized than the others, called once in a while just to chat — and possibly to avoid writing a letter.

My mother also kept a diary, one of those old-fashioned small books with psychedelic covers popular in the 1960s. Five years of entries for, say, April 8, fit on a page, with perhaps three to five lines on which you could summarize the day for posterity. “A.M. Sunny but snowed in P.M. Insurance man called.” Writing didn’t come naturally to my mother, and she seemed painfully aware of it. She told us that, when she died. she wanted her diaries burned — clearly not for their lurid content or insights into her thoughts, but, I suspect, because she didn’t want anyone to see how mundane they were. I complied, although of course now I wish I hadn’t. I did keep my own two equally dull diaries from my childhood, although I rarely look into them — there is that little of interest in my colorful childish scrawls.

As someone who is paid to write, I’ve found that most people, even those with advanced degrees, are not comfortable expressing themselves in writing. Ostensibly, they worry about such things as grammar, flow, and polish. Could I make them sound better, more intelligent, more interesting, please?

I don’t think people are afraid of their technical shortcomings as writers, whether of professional communications, day-to-day diaries, or letters to family and friends. I suspect there’s a deep-seated fear of revealing our thoughts and how we think to those who know us personally. Unlike John and Abigail, my mother didn’t have congressional congresses, wars, courts, diplomacy, or politics to write about from a firsthand viewpoint. That left her feeling like most people, who think they have nothing worthwhile to say or are afraid to say anything worthwhile from fear of offending or causing an argument or a break (something that troubled Adams less than Jefferson). So they talk about TV shows and tweet about the weather, what they’re listening to or watching, where they’re eating, perhaps what they’re reading. We’re afraid to write, or are unable to write, paralyzed by our lack of material or the unwillingness to be ourselves. We’re afraid to be judged by what we say and how we say it.

I write letters — lots of letters. For all I know, they bore the recipients. But I love the sensory experience of writing, the glide of pen across paper and the appearance of writing, which is almost magical. I may start out on one mundane topic, which leads to another, and another, and, on occasion, sometimes a broader topic of more general interest. A comment about a Victorian novel may lead to a different perspective about some aspect of contemporary life. Writing — not typing — helps me to think questions through and to remember details. Knowing that I am going to write letters keeps me on the lookout for things to write about — the lack of fireflies this summer, neighborhood news, overheard conversations, interesting perspectives on the news and the world, quirks of human behavior, including my own. Sometimes a seemingly ingenuous observation launches me into what I hope is a worthwhile digression, making me perceive a topic or problem differently. Letters allow me to think out loud in a way that a journal, with its audience of one, can’t. Even without a dialogue, I can imagine my audience’s reaction, just as perhaps John, Abigail, and the other assorted family members thought of each other centuries ago as they sat at their desks, dipped their quills, and looked out over the bleak fields of winter and the ripening fields of summer.

Communication doesn’t have to be instantaneous or uninterrupted for the emotional connection to remain strong. To remember this, read some of the most poignant letters from any war — or the letters of John and Abigail Adams. When Abigail reminded John that he was sixty years old, he replied, “If I were near I would soon convince you that I am not above forty.” Could John Adams have conveyed his feelings and the implicit compliment to Abigail so eloquently in a text message? One can only imagine how Abigail’s heart rose as she held the paper and read of his love and lust for her in John’s own handwriting.

My heart still rises in the same way when I receive a handwritten letter, no matter who it is from or what it proves to be about. It’s an old habit that dies hard — and I’m not the one to fight it. Long live the blue U.S. mailboxes.

"Enjoy it while you can"

A young man passing by said to me, “Enjoy it while you can. Only two days left!” At first I thought he meant the pool, which may remain open as long as the weather holds out. Then I thought he meant summer, which, according to some calendars, ends with Labor Day. If he had excellent eyesight (better than mine, corrected), he may have been referring to Bristol Renaissance Faire, which is mentioned on my t shirt and which concludes tomorrow. I’m leaning toward the latter because of the oddness of the comment, shot at a stranger on the other side of a fence, and the way he was looking back at me when I glanced up, as though he were checking to see if I’d gotten the joke.

It does remind me that not everyone shares my view that summer is over only with the autumnal equinox.

When does your summer end?

Lincoln Park Zoo docent program slated for extinction

Mary Schmich left a voicemail to interview me for an August 30 Chicago Tribune article, but I didn’t get the message in time to meet her deadline. I sent the following letter to the Chicago Tribune and to Schmich. As soon as I get some post-surgery energy, I’ll be writing more here.

To the editor:

As a former Lincoln Park Zoo docent during the 1990s (I was 29 when I joined the program), I read “Zoo docents fading from landscape” by Mary Schmich (August 30, 2009) with interest. During my docent service, I received laudatory letters from donors, ovations after animal presentations, and kudos for tours; helped develop a popular “Escape to the Tropics” weekend during the winter; talked to families who delighted in both the interaction and the information; participated in numerous revenue-generating programs such as family workshops; and delivered in countless other ways on what was one of the four prongs of the zoo’s mission: Education. And I was one of more than 200 people of various ages and professional backgrounds, including not only retirees, but working teachers, college instructors, lawyers, nurses, dietitians, executives, Ph.D.s, and so on, doing the same — all on a volunteer basis. To paraphrase the Peace Corps slogan, “It was the best job I ever loved.” I left it with regret for personal reasons.

According to a zoo document quoted by Schmich, “the antiquated volunteer utilization model . . . does not enhance the zoo’s strategic initiatives and often does not set up volunteers for success.” Neither “strategic initiatives” nor “success” is defined. I admit I felt successful when, for example, families paying to attend workshops requested me as their tour guide and when I could persuade children — and their parents — to overcome their fear of snakes to touch one and find out that reptiles are animals, just like us. It’s hard to believe that the docent program, and docent-guest interactions like these, didn’t benefit millions of zoo visitors during the docent program’s nearly 40-year history. Surely the education mission and the visitor experience remain important to Lincoln Park Zoo.

To find out how to enhance its strategic initiatives, Lincoln Park Zoo might consider redesigning the docent program with help from its sister institutions. For example, Prospect Park Zoo (Brooklyn, New York) “is welcoming applications for its Docent Program . . . Docents lead group tours, interpret exhibits, present biofacts and other touchables at Discovery Stations, assist in our interactive Discovery Center, work at zoo special events, and teach visitors how to interact with alpacas and sheep at our barn area. Docents who successfully complete Live Animal Handling Training are also eligible to present short Live Animal Encounters to the public, teaching children and families about animals from the Zoo’s collection of education animals.” According to the Saint Louis Zoo, “Our docents are volunteer Zoo educators who are dedicated to teaching schoolchildren and the general public about wildlife, ecosystems and conservation. In sharing their knowledge and enthusiasm about our Zoo animals, they help increase our visitors’ caring attitude toward nature. Docents are critical to the successful operation of the Zoo’s Education Department and the greater zoological community.” Closer to home, “Brookfield Zoo docents will host the next National Association of Zoo & Aquarium Docents (AZAD) Conference September 7–12, 2010.” (The 1993 national AZAD conference was hosted by Lincoln Park Zoo docents.) These, and many other zoos and aquariums with thriving, successful docent programs, can provide the kind of guidance that Lincoln Park Zoo isn’t able to obtain from a consultant focused purely on business.

Renowned primatologist and herpetologist Russell A. Mittermeier Ph.D., the president of Conservation International and the only working field biologist to head a major international environmental organization, says, “The dedication and efforts of docents are a major contribution to the education of society. Their volunteer services are exerting a real impact, particularly on this country’s young people who show a growing interest in natural history and conservation.” This fits in perfectly with the Obama administration’s nationwide service initiative.

During this severe economic downtown, when Lincoln Park Zoo has had to slash budget and staff, it seems counterintuitive to squeeze volunteers and downsize volunteer programs. And it would be deeply regrettable if Lincoln Park Zoo were to dismiss as an “antiquated model” one that so many zoos and aquariums, and environmental leaders such as Mittermeier, have embraced as essential to conservation education and human appreciation for our fellow earth travelers.

Sincerely,

Diane Schirf