Illinois & Michigan Canal (two-minute video)

Sunset on the Illinois & Michigan Canal as seen from the Texas deck of the canal boat The Volunteer in LaSalle, Illinois. Sorry for the zooms. I have to remember not to do that.

dreamer

dreamer  thinker

thinker  aspirant

aspirant

Sunset on the Illinois & Michigan Canal as seen from the Texas deck of the canal boat The Volunteer in LaSalle, Illinois. Sorry for the zooms. I have to remember not to do that.

I was reading an episode in Anne of Avonlea in which a terrifying black cloud emerges on a sunny May day, bringing wind and dropping hail, leaving devastation behind, when I left to meet J in Homewood. It was windy enough that my Fitbit Blaze was fooled into recording that I had climbed 12 floors (in reality, a few steps).

After lunch at Redbird Cafe, I noticed the buildup of impressive clouds. The day I thought would be sunny and comfortable was turning into crazy weather day, with “snow” making a brief appearance in the AccuWeather Minute by MinuteTM forecast before changing to “rain.”

While at the Three Rivers rest stop on I80, I saw I’d gotten a call from the I&M Canal Boat folks—the mule-pulled canal boat ride I’d booked had been canceled due to wind. We decided to head to the Starved Rock area anyway, possibly to go on one of the next day’s rides if the weather were better.

While it’d been windy at the rest stop, it hadn’t seemed extraordinary. Now, however, we noticed dried corn husk debris from the fields whipping around us, and leafy twigs were starting to litter the interstate. J. even ran into a small fallen branch—no time to stop or swerve. I half expected to see a skinny-legged witch fall out of the sky or Conrad Veidt to appear, saying, “Wind! Wind! Wind! WIND!”

After a stop at Jeremiah Joe, we checked out the river, which had been calm as a mirror at the end of July. The wind, about 25 mph with 50 mph gusts, was rippling the water toward the southern shore. I thought about the mules and wondered if they could get blown off the towpath. On E. 875th Rd., a government truck blocked our lane because a tree had fallen down the hillside—presumably torn up by the wind.

Given the wind and the corresponding chill, hiking didn’t appeal to me, so we went to Starved Rock Lodge for dinner. By the time we left the lodge around 6 p.m., the wind had died down, leaving behind torn branches and twigs and a strangely calm evening.

Overnight, I saw the temperature dip to 23ºF. Brrr. And it was 90ºF only a couple of weeks ago.

Sunday dawned sunny and brisk, so there was an excuse to go to Jeremiah Joe after breakfast and a soak in the spa.

The next detour was Lone Point Shelter at the eastern end of Starved Rock State Park. I walked out on the floating dock, where two pre-teen boys, one with a little white dog, did their best to make me seasick. One boy said something about falling in, so I told them the carp would eat them. One of them looked skeptical. “Carp don’t have teeth,” he said without confidence. I resisted pointing out they wouldn’t need teeth at a certain point of decay. Meanwhile, a big boat chugged between the opposite shore and an island. The size surprised me until I realized the river accommodates massive barges, of course.

We stopped at Nonie’s Bakery and Cafe in Utica to pick up sandwiches to go for dinner on the road since we were going to get a late start back. Nonie’s is a quaint place in a house that looks like a house, inside and out.

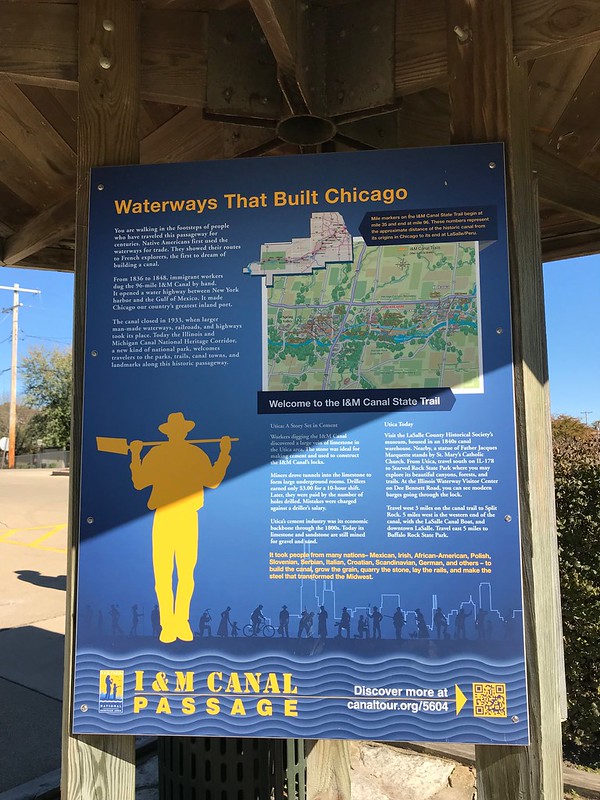

After Nonie’s we stopped at a different pedestrian bridge over the Illinois and Michigan Canal in Utica. I wonder what will happen to bridge and detailed signs once the canal is filled in, as I read is planned in the not-too-distant future.

Now we set out for our main objective—Lock 16 Café and Gift Shop in LaSalle. The kitchen closes at 3, but we made it there in plenty of time for a late lunch and to look over the goods. Who can resist a “Moe and Joe” mule t-shirt? Not I.

The ride, complete with ghost stories, was to start at 5, so we wandered around the lock (Lock 14, not 16), where a number of men and boys were fishing for trout—one fellow had four on a line in the water. I wondered how far the canal goes.

I didn’t see any sign of mules or tack. I knew Joe had died last summer. After boarding we found out Moe, age 45, had died of Cushing’s disease a couple of weeks earlier. The remaining mule, Larry, had hurt himself where the belly band would go. Smart mule. One passenger said, “What? No Shemp?” Our guide told a credulous boy that the canal ride to Chicago would have taken 24 hours compared to a week for a carriage.

Our host told us amusing tales about the mules competing with each other (pulling the boat out of the canal when in tandem, or completing the hour-long trip in 40 minutes when one was in front of the other). If one pulled, the one left alone would have panic attacks, so a nanny goat was procured to keep him company—until the two teamed up to pick on her. Even gone, Moe and Joe were stars.

Our ghost storyteller was paranormal writer Sylvia Shults, who started off with a tale from Seneca, Illinois, about spontaneous combustion. Reflect on that the next time you want to say, “I’m so mad at her! She burns me up!”

On my previous mule-pulled canal ride, on the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Canal starting in Georgetown in Washington, D.C., the boat had passed through a lock first thing. I remember the boat lowering and seeing the slimy green-covered wall appear (or I think I do—I may be confusing it with a boat ride in Chicago).

There are no locks on the short I&M ride, and Lock 14 (immediately behind where the boat is docked) looks like it hasn’t been used in years. In this case, the boat, dubbed The Volunteer, passes under a bridge at Joliet Street. As it falls under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Coast Guard, passengers are required to remain seated as there could be a jolt if the boat bumps near the bridge. It did, and there was. If I’d been standing, I’d have keeled over. Wooomff.

As soon as I could I walked up the steps to the Texas deck, while J. alternated between above and below. Naturally, just after he went below a great blue heron flapped its ponderous way toward us. “What is THAT?” a woman asked me. I was tempted to reply, “A pterodactyl.” It’s a rare moment when I’m the resident bird expert.

I watched from the bow as The Volunteer approached a trestle, beyond which is the Little Vermilion River Aqueduct. I could see that we would have to start to make our way back—the canal narrows and appears to be shallow. I learned later the canal had been restored in this location specifically for the canal boat ride. Someday we’ll have to see more by walking the I&M Canal trail. On our return trip, a woman on the boat called out to a woman on the trail: “How far does that path go?” They had to yell back and forth several times, but I think the walker said Ottawa. I’ll be lucky if I can make it past the trestle.

In Google Maps’ satellite imagery, the canal is a frightening neon yellow-green, although it looked okay as far as I could tell (and the men and boys fishing clearly the intended to eat their catch!).

This ride was timed just right to head back toward the golden glow of the setting sun, which wasn’t blindingly bright. Despite the distant pounding from Illinois Cement to the east, the trip was calming, and I wished the glow could last a bit longer.

Not surprisingly, Ms. Shults was selling and signing her books so before disembarking I bought a couple after telling her I was interested equally in history and ghosts. She recommended a book on an asylum in Peoria . . .

We had a long trip and a work day ahead, so reluctantly we headed toward the parking lot prepared to leave. It was then I spotted the silhouette of a mule, similar to the metal cutouts of historical figures we’d seen dotting the area. Then I noticed it had a couple of tones, unlike the cutouts. Then it swung its head. It was Larry the mule! We ran over to meet Larry and found him eating apples from Ms. Shults’ hand. After she’d run out of goodies an older man came along this carrots and marshmallows, and a woman pulled a little grass as a treat. It wouldn’t surprise me if Larry returns to his farm in Utica in early November weighing a wee bit more, even after a summer of canal boat pulling.

After the visitors bearing gifts left, Larry, who’d walked away from me several times to follow them, suddenly started pushing my left arm around with his head and exploring my sleeve with his big mule tongue. Alas, I had no apples, carrots, or anything else a hungry mule might be interested in. If I ever get a chance to go back to LaSalle for a mule-pulled canal boat ride, I’ll know to bring healthy mule bribes, er, treats.