Once or twice a year I travel by Amtrak from Chicago’s Union Station — not cross country, just to Altoona, Pennsylvania, and Ann Arbor, Michigan. The Capitol Limited, Pennsylvanian, and Wolverine routes pass through cities, small towns, farmlands, and rusted sections of the Rust Belt. I ride the Wolverine during the day. The journey east on the Capitol Limited is all after dark, but on the return west we are in Indiana when morning dawns.

Steel and power

Amtrak passes through northwest Indiana, where in the late 1800s and early 1900s much of one of the nation’s most diverse ecosystems, the Indiana Dunes, was bulldozed over or carted off (see Hoosier Slide). Shifting Sands: On the Path to Sustainability shows the making of places such as Gary, Indiana, and the long-term costs of short-term gains.

I’m not sure Amtrak goes through Gary, but it stops at Hammond-Whiting, where the view from the train overlooks like an industrial post-apocalypse. That’s the nature of trains — industry and train tracks go together like chips and salsa.

41 40′ 13.20″ N, 87 28′ 7.20″ W

If you were to travel through only northwest Indiana by Amtrak, you’d think the world is made up of industry, utility poles, and casinos. By car, you’d also see billboards for fireworks and adult stores, and countless personal injury and illness attorneys.

41 37′ 11.40″ N, 87 9′ 54.60″ W

41 46′ 37.00″ N, 87 37′ 22.23″ W

41 41′ 47.97″ N, 87 30′ 53.49″ W

On the train, I sleep sporadically. One early morning I woke up to find the train stopped near this structure and garish lighting in Cleveland, Ohio. What could be more representative of industrial eastern America?

41 30′ 17.11″ N, 81 41′ 50.43″ W

Weeds flourish, trees struggle, oily water lies in pools, buildings and train cars rust aggressively, and stuff is strewn everywhere. Human beings seldom appear, although parked cars indicate their presence. In black and white, in color, in summer, in winter, the view is bleak.

A bit of nature

I’m fascinated by where cemeteries appear — sometimes unexpectedly in the woods or at state parks like the Smith cemetery at Kankakee River State Park, Illinois or the Porter Rea Cemetery at Potato Creek State Park, Indiana. This one is on Mineral Springs Road in Indiana, where I94 passes over the train tracks. I couldn’t tell at the time, but it belongs to Augsburg Church, a Lutheran church in Porter. It’s about two miles from Bailly Homestead and Chellberg Farm, which are part of Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, past most of the worst of the industrial areas.

When I see puffy clouds, an eggshell sky, and verdant trees on a June day in Michigan, I can’t wait to get to my destination to soak it all in.

Buildings

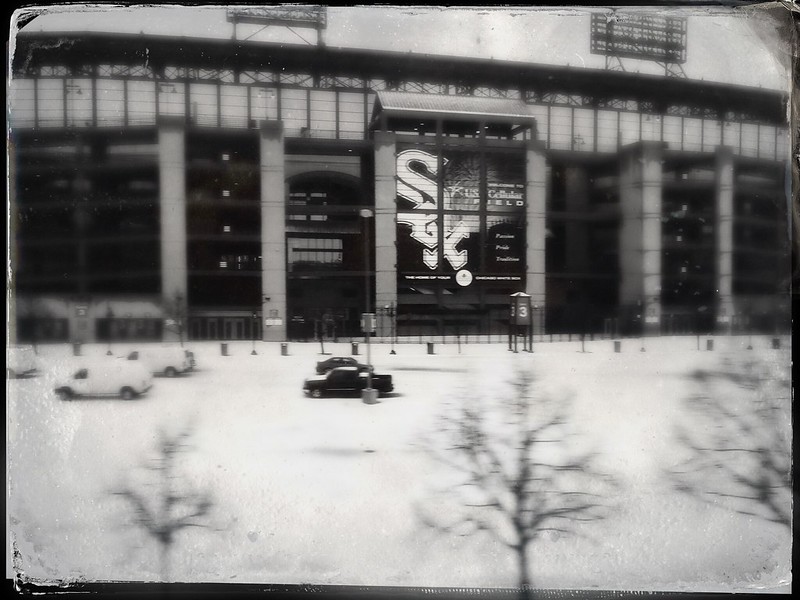

Whether you call it Cellular Field, Guaranteed Rate Field, or Comiskey Park, the home of the White Sox is sometimes a surprise highlight for Amtrak passengers. If you look at the satellite view of the ballpark, though, you won’t believe the number of train tracks to its west. On the starboard side of the train, eastbound Amtrak passengers can enjoy the view of Universal Granite and Marble.

(I don’t like other names)

Apparently a scrapyard in Michigan City, Indiana, has mastered Monty Python’s art of “putting things on top of other things.”

41 42′ 25.80″ N, 86 54′ 34.80″ W

I couldn’t figure out the purpose of this attractive building with cupola, but was surprised to realize later it’s in Michigan City, Indiana, not far from the Old Lighthouse Museum. The Hoosier Slide mentioned above was across from the lighthouse on Trail Creek where it empties into Lake Michigan, near this building. That would have been something to see from an Amtrak train. Now the Hoosier slide site is covered by a NIPSCO coal-fired plant. Progress. Rest in peace, Hoosier Slide. May we not forgot what we have lost and never known.

41 43′ 18.18″ N, 86 54′ 15.75″ W

This wavy fence in Michigan City, Indiana, baffled me. I’ve seen them elsewhere, I think, but I don’t know the purpose other than aesthetic.

41 47′ 48.26″ N, 86 44′ 41.29″ W

There may be millions of nondescript, decaying buildings across the U.S., but I haven’t spotted many more nondescript than this one.

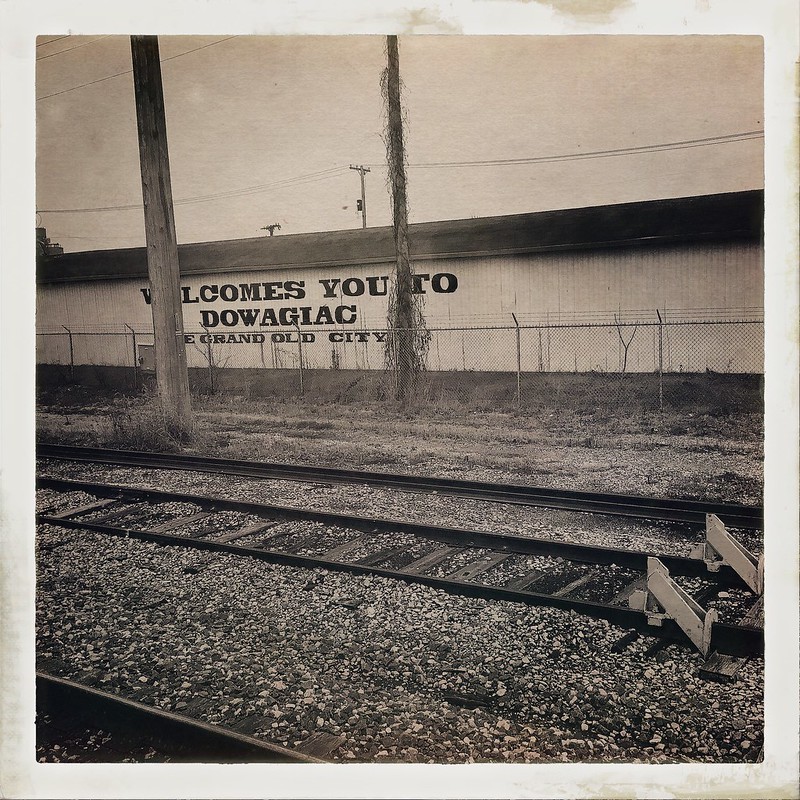

The appearance of this building belies its message that Dowagiac, Michigan, is the “Grand Old City.”

41 58′ 50.28″ N, 86 6′ 34.05″ W

I noticed this long red building on the edge of a small stand of trees in Parma, Michigan, east of Battle Creek. In the satellite view, a dirt road from another building, likely a house, is the only access to it. I’m intrigued by the tall chimney.

42 15′ 36.00″ N, 84 36′ 4.80″ W

With no immediate neighbors, this house, likely part of a tree farm, looks lonelier than it is.

42 15′ 55.80″ N, 84 35′ 5.40″ W

Farm buildings dot the back roads, and rails, of middle America.

42 15′ 51.60″ N, 84 34′ 47.40″ W

Some houses in Pennsylvania towns like Johnstown are spaced closely together, with nearly touching side walls or an alley almost too narrow to squeeze through.

40 20′ 34.94″ N, 78 56′ 14.80″ W

These houses on a hill are farther apart. I wonder if they would have been high enough to escape the Great Flood of 1889—or any since. The area’s geography makes it prone to flooding even without breaking dams.

Johnstown, too, has nondescript commercial buildings.

Stations

Some Amtrak stations, like the modern monstrosity in Ann Arbor, are cold and utilitarian. Next door, Ann Arbor’s former station has been converted into an upscale restaurant, Gandy Dancer.

Old school stations remain in use in Michigan and Indiana.

42 14′ 52.20″ N, 84 23′ 58.80″ W

42 14′ 52.20″ N, 84 23′ 58.80″ W

Often there’s not much to see in the dark, but I spotted the same rotting cars from the EB Capitol Limited. Nearby I found a National New York Central Railroad Museum. If they’re intended to be exhibits, they may use a little work.

Elkhart, Indiana

Coming and Going

The morning Dan Ryan Expressway from Amtrak.

This is what you, and New Buffalo, Michigan, look like to an Amtrak passenger.

As children, we liked to watch for the caboose at the end of long freight trains. When the news pronounced the demise of the caboose, I was distraught. When I can, I watch the scenery recede from the last car of the Pennsylvanian, unimpeded by a caboose, remembering the miles of track and the cities, towns, stations, farms, taverns, fields, rivers, creeks, houses, plants, and stores behind me — and ahead of me on the return.

Finally, all journeys must have an end. Mine passes over the Calumet River through Chicago’s steel history.