Sea smoke on Lake Michigan at -21ºF

It got colder this morning before it got warmer. The sea smoke was curling and eddying in interesting ways.

It got colder this morning before it got warmer. The sea smoke was curling and eddying in interesting ways.

Today is the 100th anniversary of my mother’s birth. I discovered this delightful clipping about a hike to a farm and a picnic with storytelling under a big tree she helped to organize. It could be straight out of Anne of Green Gables.

I love finding these blurbs. This and others are giving me new insight into my parents’ early lives pre-me.

As a child, I didn’t think about water until I started visiting a friend whose family drank well water that smelled and tasted of sulfur. The odor permeated their house. “You get used to it,” she said. Accustomed to the tasteless taste of “city water,” invariably I felt thirsty the moment I arrived. I never got used to it.

Forty-five years ago the typical person didn’t carry a water bottle or buy bottled water. We drank whatever came out of the tap. Unswayed by Dr. Strangelove or decades of bottled water marketing, I still do, and that’s what I fill my insulated water bottles with when traveling.

On our annual pilgrimage to Pennsylvania in the 1960s and early 1970s, we used to stop at a couple of roadside springs and fill a jug or two with spring water. We didn’t need to. Our “city water” in New York was fine with us — well, as fine as any water in our polluted world can be. There didn’t seem to be any objection to our hosts’ water, either. By the time I was sentient, we were no longer staying with anyone who lacked indoor plumbing. My guess is my parents liked the idea of getting water from a roadside spring and preferred it as a rare treat. I did too. Water straight from a spring — as nature intended. (We didn’t boil it, either.)

Later we stopped at the usual places and found signs indicating the water was too contaminated to drink — the effects of coal mining. My heart broke a bit at the loss of a tradition and the sense the earth itself was dying one roadside spring at a time. After all, I was being raised in the era of the fiery Cuyahoga River, algae-choked Lake Erie, and the horrors of Love Canal.

I wish I could remember where those springs were and find out if anything has changed.

According to findaspring.com, which seems to be defunct, Pennsylvania leads the U.S. in the number of listed springs with 84. New York is second with 59, while Illinois lags behind with only 17 shown.

When I was visiting my cousin for Christmas 2018, I found out they’ve taken to collecting and drinking spring water. My cousin hinted, however, that the spring is far from picturesque. In my mind’s eye, I saw an ugly, chipped-up plastic pipe protruding from an ugly, denuded hillside in town. Something like that.

The spring is south of Tyrone, so we used a visit to Village Pantry as an excuse to get some water. It’s on a lightly traveled road paralleled by a stream, Elk Run, that seems to cross back and forth under it in several places.

My cousin and his wife quickly set up an efficient two-person jug-passing and -filling operation while I meandered back and forth across the road, drinking in (so to speak) the sights and sounds of the spring and Elk Run on its journey.

When a house buyer sees a stream, he pictures flooding, damage, and dollars. I picture myself at a church picnic at Chestnut Ridge, a lifetime ago, walking on 18-Mile Creek, listening to its gushing and trickling, soaking in the sight of countless tiny drops, waterfalls, and eddies, and hoping to spot tadpoles, frogs, minnows, and fish in the clear water reflecting a perfect summer sun filtered on the edges by healthy trees. I had no way of knowing how ephemeral that experience would be.

Memories.

I don’t know how clean or safe the water from this spring is. As I said, it’s south of Tyrone, whose paper mills wafted their distinctive odor through my aunt’s screen door seven or eight miles away in Bellwood. I’ve seen a discussion about agricultural runoff in the area as well, although many think it’s insignificant.

Elk Run appears to be a tributary of the Little Juniata River. I once told my dad I’d seen a leopard frog in the Little Juniata as it runs past Logan Valley Cemetery in Bellwood. He made a wry comment about it, perhaps “How many legs did it have?” Now he and my mother are buried in Logan Valley. Cemetery, within earshot of the Little Juniata. Water, however clean it is or is not, connects us — all of us. We shouldn’t forget that.

Curious about the current state of the Little Juniata, given I’d been handed two bottles of spring water, I found out it’s not as bad as I thought.

Well, the Little Juniata River is not well-known nationally, primarily because it’s only been a trout stream since around 1975. The reason being that prior to that it was literally an open sewer.

Bill Anderson, president of the Little Juniata River Association

After decades of pollution and a “mysterious pollution event in 1997,” we have brown trout fishers to thank for cleaning up the Little Juniata and shoring up its eroding banks.

We want to make sure this resource stays open for our children and grandchildren.

Bill Anderson

This would have made Dad happy. And he didn’t fish.

I jest, but this does bring back memories of visits back and forth when I was young enough to be bored but old enough to appreciate any change in routine. This was a visit without us, though.

This morning I, “Dianne Schirg,” made this marvelous discovery from a simpler time when a family visit to Bellwood, Pennsylvania, was noteworthy.

I haven’t moved since I posted “Magnetic personality” in 2008, but my refrigerator was replaced with a newer model in a different location after an apartment remodeling. Not too long ago, I finished redecorating it with magnets I’d found recently. Here we go:

Do you remember Fotomat? You drove up, dropped off your film, and got your photos back the next day. (I can’t swear they were always on time.) If you don’t recall the distinctive Fotomat kiosk, you may be familiar with the idea from That 70s Show. The name was disguised as Photo Hut, which loses the charm of the alternative spelling common in the era’s advertising and the nod to the old-school automat.

Fotomat seems like a natural extension of mid 20th-century culture. Interstates, drive-in restaurants and movie theaters, motels (motor hotels) — why not drive-up film processing and prints?

In Hamburg, New York, the nearest Fotomat couldn’t have been any closer to us. It was plopped near the outer edge of the South Shore Plaza parking lot, where my dad could stop on the way home from work or to the store. If he’d been so inclined (and willing to dodge Route 20 and parking lot traffic), he could have walked over from the trailer park.

My dad liked Fotomat because they used Kodak processing and film for his primarily 126 film prints. He could be snobbish about certain brands, and Kodak was one of them. If I remember right, our South Shore Plaza Fotomat and others switched to another brand, possibly Fujifilm. That’s when and why he began to use Fotomat less frequently.

According to Wikipedia, the photo minilab made Fotomat obsolete in the late 1980s. The brand continued online with photo storage and editing until 2009. It’s funny to think of a brand built upon its unique physical locations and look surviving (barely) as a virtual service.

South Shore Plaza, opened in 1960, died a long, painful death, finally torn down and replaced by a Wal-Mart in 2009. I’d guess the Fotomat succumbed long before the plaza emitted its final gasp.

As we know from many creepy images of Poconos resorts or old amusement parks, when an idea or place is abandoned, it’s sometimes left in place until it falls apart or something comes along to take its place. Some of the 4,000 Fotomat booths remain, repurposed. Drive-through coffee or cigarettes, anyone?

Further reading: Democrat & Chronicle, “Whatever Happened To … Fotomat?”

On my last full day in Pennsylvania, the 28th, we went to the Flight 93 National Memorial despite the government shutdown. Our route took us down Lincoln Highway, which crosses the United States. It passes through Illinois in the far south suburbs of Chicago. Lincoln Highway reminds me that all of us are connected in some way.

We arrived first at the Tower of Voices, which with the surrounding landscaping are a work in progress. When completed, there will be a chime for each crew member and passenger on Flight 93 — 40 in all. At this time, there were eight if I recall correctly.

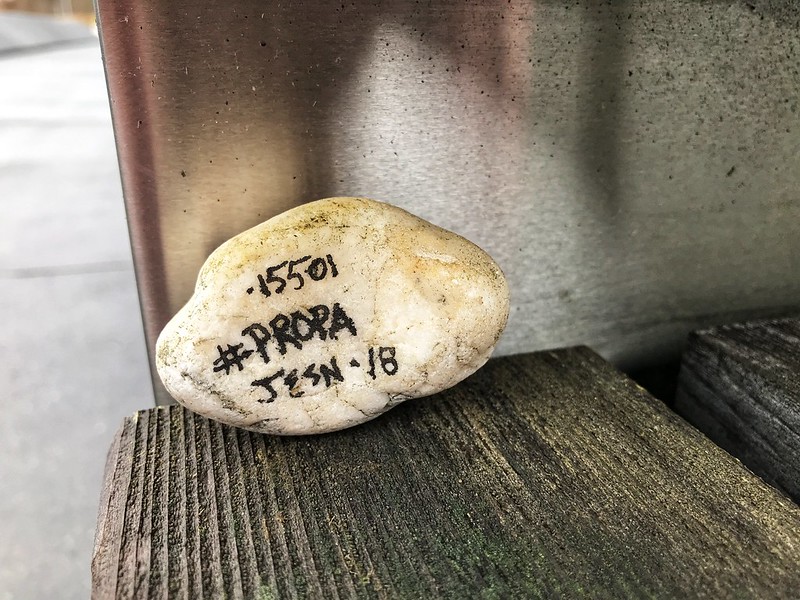

On a bench near the Tower of Voices, we found a “Painted Rock of Pennsylvania.” This is a thing I must look into. I loved this one.

The memorial site is a few miles off, with some farm buildings and wind turbines the main signs of habitation. Before 9/11, the residents of Shanksville and environs could not have imagined visitors from around the world making pilgrimage to their community a half hour south of Johnstown.

The site, which is large, was once a surface mine, stripped of most trees and since replanted. Due to the shutdown, the date, and possibly the gloomy but unseasonably warm weather, there were some but not many people about. We took our time walking to the wall where the names are inscribed, passing the large sandstone boulder that marks the area where the plane came to rest — violently. Someone had left flowers by a few of the names in the wall.

We found another Painted Rock of Pennsylvania on a bench along the way.

I found out via the Facebook hashtag #PROPA that the artist hadn’t expected them to be found until spring. I left both for others to find.

On the way back to the parking lot, we looked at some graphics, then drove to the visitor center. The high walls, marked with the hemlock lines that are the prevailing theme even in the sidewalks, show the path the plane took. In this case, the design’s simplicity adds to the solemnity of the place and inspires the imagination, especially when you remember this horrific event took place on a perfect sunny day in the waning summertime.

The visitor center was closed, of course, but we could see quite a bit through the glass. I wouldn’t have wanted to eavesdrop on those final conversations even if I could have.

On Lincoln Highway, I’d noticed signs for two covered bridges that didn’t seem to be far off — two or three miles, more or less. The first, Glessner Covered Bridge, was down a well-maintained dirt road — not too rutted. The covered bridge is lovely, with a barn on one side and railroad tracks that parallel the stream on the other. The stream is known as either Stony Creek or Stonycreek River. The latter seems redundant. It’s either a river or a creek, but neither is a clearly defined term.

The generous landowner at Glessner covered bridge has posted signs — not the usual “Private,” “Posted,” “Keep Off,” etc,., but signs inviting you to enjoy a little fishing if you’re so minded. I call that right neighborly. It would be a lovely spot to fish in the warmer months.

To get to Trostletown Covered Bridge, we passed Stoystown Auto Wreckers, quite possibly the largest junkyard I’ve ever seen — acres and more acres of junk cars at the bottom of rolling hills. As I recall, the Google Maps capture shows only a portion of the junkyard. Today — unsightly metal carcasses. Yesterday — bucolic covered bridges.

Google Earth image shows the size better.

I’ve read in several places that Trostletown Covered Bridge passes over Stonycreek, or Stony Creek River(?). I use a question mark because Google Maps shows Stony Creek River west of the bridge. I wonder if what we saw is a little offshoot — it doesn’t even appear on Google Maps in blue.

The water, wherever it comes from, doesn’t quite flow freely under Trostletown. It was low and in many places choked with plants and earth. Unlike Glessner Covered Bridge, which is open to cars, Trostletown doesn’t seem to lead anywhere, but ends in a seedy and weedy area. I’d want to plant a butterfly garden with benches there.

I teased my cousin’s wife about driving across the Trostletown Covered Bridge, but she’d already noted it goes nowhere. I drew their attention to another deterrent — a Conestoga wagon blocking the way.

Google Earth shows Trostletown Covered Bridge to your right from the bend in the road.

Trostletown Covered Bridge and the Conestoga wagon are not the only remnants of history here. Kitty corner from the covered bridge the Stoystown American Legion post features a tank and a helicopter positioned to nosedive into the ground. I read elsewhere it’s a Vietnam-era Huey.

On the way to and back, mist smothered and covered what lay in the hollows, often following the meanderings, we thought, of streams and rivers. You can’t quite capture it from a moving vehicle.

Although the day had been gloomy, there was one brief hint of life and color as the sun appeared while making its daily disappearance.

Days like this make leaving harder than it already is.