Monthly Archives: February 2020

Octave Chanute: Patron Saint of Flight

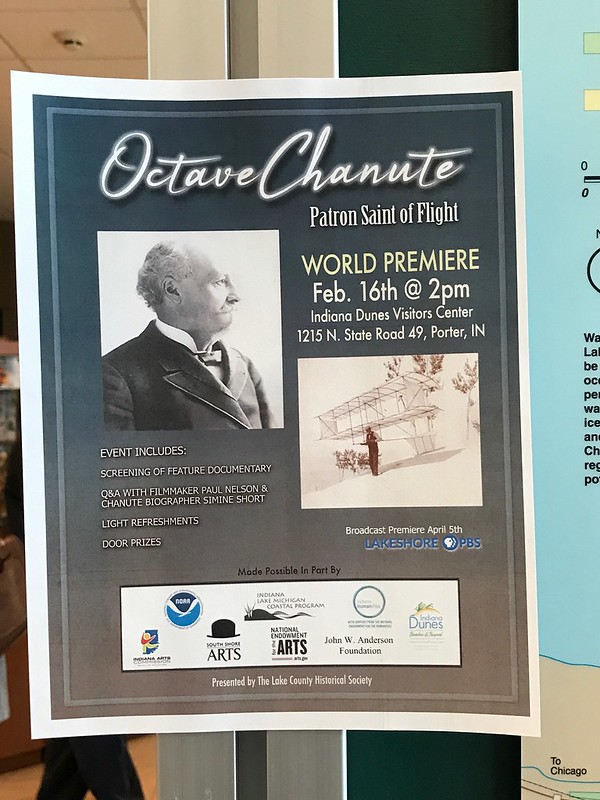

Facebook has many flaws, but it does alert me when events I might be interested in are coming up. A few weeks ago I found out about the world premiere of Octave Chanute: Patron Saint of Flight, at Indiana Dunes Visitor Center. I knew the Chanute name vaguely from the old Air Force base, but I couldn’t have told you then where the base had been located or why it was named Chanute. This sounded like a way to get in a visit to Indiana Dunes, learn something, and spend what might be otherwise a dull winter afternoon, depending on the weather.

The parking lot was unusually crowded, and when J and I walked in about a half hour early, a good-sized group was watching Shifting Sands: On the Path to Sustainability, a documentary on the history of Indiana Dunes and efforts to restore what can be restored. It’s meant to inspire, but it’s also tragic and depressing.

By the time Shifting Sands ended and Octave Chanute was scheduled to begin, the auditorium had filled up, even when extra folding chairs were brought out. Soon it was standing room only.

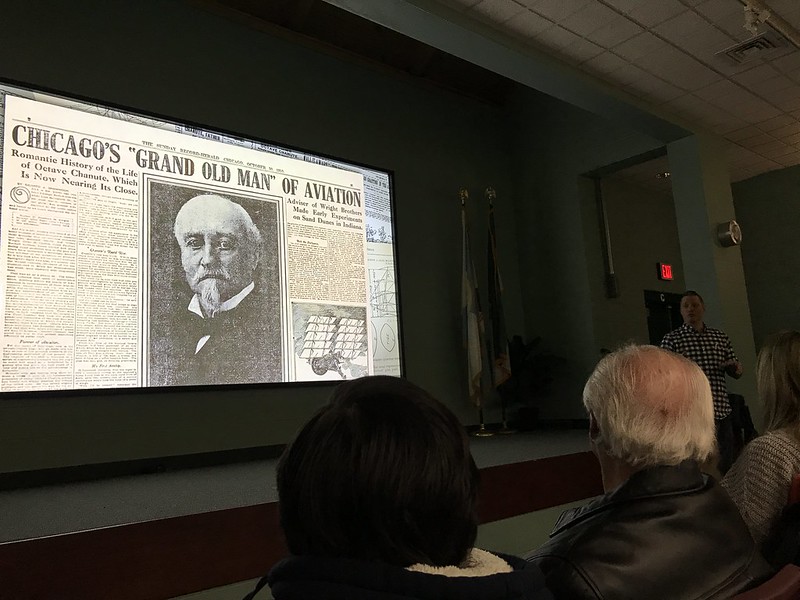

Simine Short, author of Locomotive to Aeromotive: Octave Chanute and the Transportation Revolution, and young director Paul Nelson introduced the film. I mention Nelson’s relative age because the audience was mostly 50 plus, possibly 60 plus, which disappointed me because I would like to see younger people interested in history. Of course, when I was younger none of my peers would have been interested, either.

Bridge 16, or the Portage Bridge

The presentation began with some technical glitches (flashbacks to every high school A/V club everywhere!), but my ears perked up at the mention of the Portage Bridge, accompanied by a photo I recognized immediately. Through this film, I found out Octave Chanute was the engineer behind the much-loved railroad bridge over the Genesee River at Letchworth State Park in New York.

Known for his bridges, Chanute was called in when the original timber trestle, the longest and tallest wooden bridge in the world when it opened in 1852, was reduced to ashes on May 6, 1875, after a train had passed over (spark?). Chanute’s iron replacement opened only 86 days after the fire. According to Short’s book, the piers were rebuilt and the uprights and girders strengthened in 1880, “making the bridge better than new.”

The original timber Bridge 16 over the Genesee River

Although modern Norfolk Southern trains were restricted to 10 miles per hour over the Letchworth gorge, Chanute’s bridge lasted until 2017, when the Genesee Arch Bridge opened. The state of New York declined the offer of the 1875 bridge, the last of which was demolished on March 20, 2018. I’d been fortunate to visit the old bridge one last time in 2015. When I’d found out about the premiere of this film, I’d had no idea it would take me back to perhaps the most iconic of my childhood memories. I remember walking along those tracks with my brother during one of his visits.

But wait! There’s more!

Kinzua Bridge

My ears perked up again at the mention of Kinzua Bridge. I’d found out about Kinzua Bridge State Park when I was looking up Kinzua Dam, another place I’d visited as a child, for my 2015 swing through Ohio, New York, and Pennsylvania.

It turns out that Octave Chanute was behind the original 2,000-foot-long Kinzua Bridge (or Viaduct), built in 1882 at 302 feet above the narrow valley floor. Short calls it Chanute’s “most spectacular bridge.” She adds that the bridge was rebuilt in 1900 “to keep up with the increasing volume and weight of the coal traffic.” Carl W. Buchholz redesigned the superstructure on the original masonry foundation piers.

By 1959 the viaduct failed safety inspections and was closed to commercial rail traffic. Restoration began in 2002, but in 2003 an F2 tornado “tore eleven towers from their concrete bases. Investigators found that the anchor bolts, installed under Chanute’s supervision, had rusted over the past 120 years.” Over time, the materials had failed the design.

After seeing this film, I’m even happier that I had the opportunity to walk out on what’s still standing of Kinzua Bridge and get a look at the remnants resting in peace on the valley floor. Even destroyed, Kinzua Bridge is indeed a “spectacular” sight.

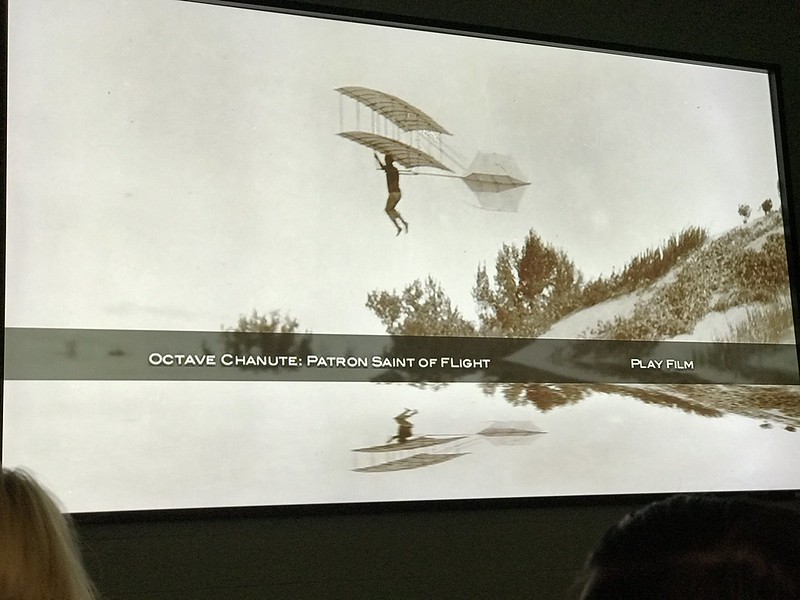

Why Indiana Dunes?

Of course, most of the film was about Chanute’s contributions to flight and relationship with Wilbur Wright (rocky; Chanute was an open source kind of man and Wilbur believed in closely held information). What’s the link to Indiana Dunes? With their lake winds, elevations, and soft sand, the Dunes were Chanute’s choice for safely testing their experiments — the Kitty Hawk of the Midwest.

Epilogue, March 8, 2020

Octave Grill in Chesterton is named for Octave Chanute. Found out they serve a Chanute burger.

Lodgings I have known: Temple Hill Bed & Breakfast

It’s high time I wrote about some of the places I’ve stayed — not the chains, but bed and breakfasts, inns, and other local places.

Steeped in history, May 25 and 26, 2015

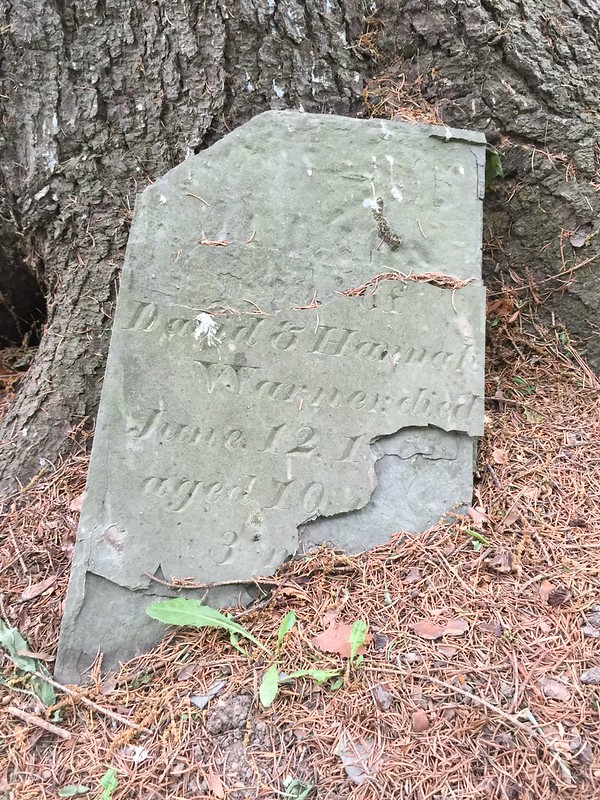

Temple Hill Bed & Breakfast, built in 1826 in Geneseo, New York, as an academy of higher education for young men, is nestled amongst older trees across from Temple Hill Cemetery, which dates from 1807. It’s a grand house, with a circular driveway that makes you feel like you’re entering an English estate on a BBC series. Why I don’t have a photo of the exterior baffles me.

The owners have a dog and some free-range cats. I stayed in the Academy Room, where I made a big thud when I fell in the Jacuzzi tub. I don’t have photos of the room either.

Although it was too early for the pool to be open, we did get a peek at the garden, complete with a tea room pagoda in progress. I’m a little fuzzy on the details as already more than two-and-a-half years have passed.

Upstairs there was an open room with books and games that reminded me of a scene early in the film Moonrise Kingdom. It was hard to leave that too, even if I didn’t have time to spend there.

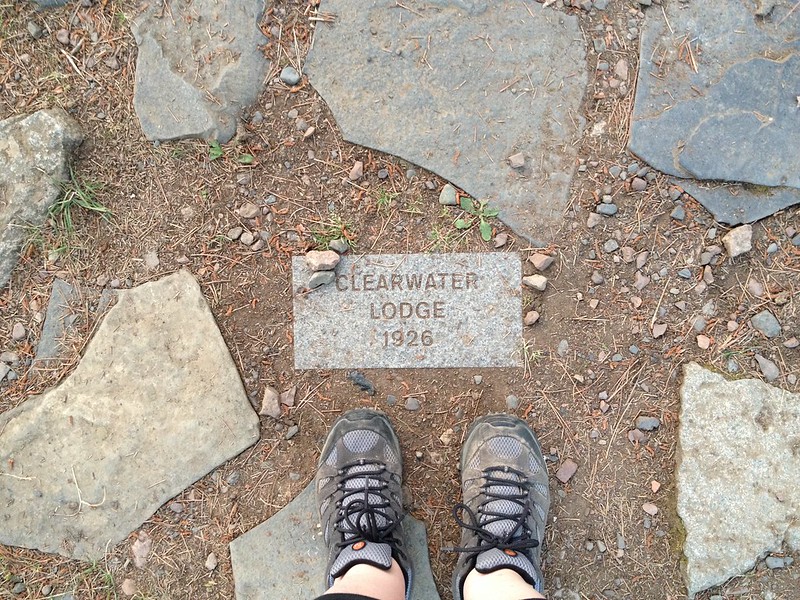

Lodgings I have known: Clearwater Historic Lodge

It’s high time I wrote about some of the places I’ve stayed — not the chains, but bed and breakfasts, inns, and other local places.

Steeped in history, August 5, 6, and 7, 2014

Like Rippon-Kinsella House in Springfield, Illinois, Clearwater Historic Lodge is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Located off the Gunflint Trail west of Grand Marais, Minnesota, Clearwater Historic Lodge overlooks the lake and palisades, although I remember a healthy stand of conifers filtering the view. It’s also a great spot for getting outfitted for a Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness adventure.

At Clearwater Historic Lodge, I thoroughly enjoyed: a lengthy thunderstorm that started after we had carried most of our things in, watching small shapes (likely bats) flit around in the inky darkness, the view of the lake through the trees from the back porch, the view of the lake from the imaginatively named Suite A, a brief canoe outing and the view of the distant palisades before black flies ate my ankles, the gift shop, and the comfortable main room.

With places to go and things to see, I didn’t have nearly enough time at the lodge.

At breakfast I found out one of the employees was a descendant of the original owners. I think she said she had never been in a canoe. I couldn’t imagine.

A stay at Clearwater Historic Lodge forces you to give up your constant attraction to the online world. Daytime’s slow satellite connection is limited (and a guest had inadvertently used up the monthly allotment on videos). In the wee hours, access was unlimited, but the cloud cover and/or the trees, which I loved, seemed to make it erratic. You can almost get away from it all and focus on the Gunflint Trail experience you can’t have anywhere else.

Below is part of the Clearwater Historic Lodge entry for the National Register of Historic Places, aka places I hate to leave . . .

The oldest surviving guesthouse on the Gunflint Trail, Clearwater Lodge is historically significant for its pioneering, and continuing, contribution to the Cook County tourist industry.

In 1893, the Cook County Board of Commissioners finished the last stretch of road linking Grand Marais to Gun Flint, a mining community about 45 miles north on the Canadian border. Although the completion of the “Gunflint Trail” was primarily a testimony to the political power of the county’s mining interests, the road was also a boon to homesteaders who settled the area during the early 1900s.2 Among these early residents were Charles (“Charlie”), and Petra Boostrom, who, in 1916, purchased 80 acres of land on the western shore of Clearwater Lake, just east of the Superior National Forest. There the Boostroms erected a small log cabin. Over the next ten years, Charlie earned a reputation as one of the area’s foremost trappers and hunters.

During the 1920s, an increasing number of tourists discovered the woods and lakes of Cook County, and Charlie found an increasing part of his livelihood as a guide for sport hvinting and fishing parties. To capitalize on the emerging tourist trade, he and Petra constructed Clearwater Lodge in 1925-1926. Completion of the building coincided with the construction of an automobile road connecting the new resort to the Gunflint Trail. Over the next two decades the Gunflint Trail developed into a major vacation spot, and Clearwater Lodge earned a statewide reputation for its hospitality. After the Boostroms retired from the tourist business in 1945, Clearwater Lodge went through several changes in ownership until, in 1964, it became the property of Jack (“Jocko”) Nelson and his wife Lee. The Nelsons renamed the resort “Jocko’s Clearwater Lodge.” Although Jack Nelson died in 1978, his widow continues to operate the lodge as a summer resort.

Lodgings I have known: Rippon-Kinsella House

It’s high time I wrote about some of the places I’ve stayed — not the chains, but bed and breakfasts, inns, and other local places.

Steeped in history, April 24 and 25, 2010

April 25, 2010

While visiting the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Museum in Springfield, Illinois, I stayed at the Rippon-Kinsella House, which is on the National Register of Historic Places and has a Wikipedia entry. I think I may have stayed in the Maid’s Room, the smallest of the three rooms. The house is very elegant, but what I remember most is the garden, which is lovely, and the residential area around it. The owners were charming and amused but helpful when we tried to find a restaurant in Springfield open after 9 p.m. Sadly, it sounds like one of the owners has become seriously ill, and the inn closed December 31, 2017.

You can find out more about Rippon-Kinsella House’s history from its entry form for the National Register of Historic Places (PDF).

Windy day at Wolf Lake

February 2, 2020, or 02022020

Groundhog Day. Super Bowl Sunday. (How far into winter can the Super Bowl go? At this rate, it will conflict with spring training.) This seemed like a good day to practice wielding a 150–600 mm lens in high wind conditions at Wolf Lake, which spans the Illinois/Indiana border. On the way, it was amusing to hear the Google Maps voice say, “Welcome to Illinois,” although she forgot to welcome us to Indiana or back to Illinois in the zigzagging we must have done.

Part of the heavily industrialized Calumet region, Wolf Lake seems to be a hunting and fishing paradise, although with the heavy industry around it, I’m not sure I’d want to eat anything that swam in or floated on its waters or walked the surrounding land, some of which is on a slag foundation.

On this day, as on others, Wolf Lake could have been Swan Lake. Our first sight from the road that serves as part of the state line was of five non-native mute swans. I can’t be certain, but I suspect they’re the pair with three cygnets I’d seen several times while passing Wolf Lake on the way to Indiana Dunes National Park. (Not only is Wolf Lake sandwiched between heavy industries, but it’s passed over by I-90, aka the Indiana Toll Road, the primary connection between Chicago and northwest Indiana. There’s nothing like slag heaps, noise pollution, and car fumes from a busy interstate near what was once pristine wetlands.)

While mute swans are beautiful, I don’t care for them as a non-native species. We saw at least 12 on the west side of the lake, which seems to be their preferred habitat — perhaps due to the several dikes that divide the lake. That’s a lot of swans with a lot of forage needs for a small lake. I’m told, however, that a few days later someone spotted endangered trumpeter swans as well as mutes.

I’d stupidly forgotten the camera card, which made lugging the long lens along pointless. J graciously lent me his for some shots. Even as the whipping wind blurred most of my photos (helped by a shaky, cold hand), it ruffled the swans’ feathers. The seemed inclined to hang out in their area. Maybe they were avoiding the swans by the other dikes.

And that’s how I happily avoided Super Bowl Sunday. This year.