9 September 2018: I caught this bee celebrating the winding down of summer on its favorite plant. I wish I were so limber. Maybe I could be if I lacked a spine but had six legs.

29 April 2018: While on the way to the Shirley Ryan Ability Lab, I noticed people were looking down and skirting something on the sidewalk. From a distance it looked like it might have been a pigeon, which could account for the apparent distaste.

When I got closer, this is what I found—a beautiful belted kingfisher, killed when it hit building glass during spring migration. It’s fall migration already—a time to see more beautiful avian visitors passing through. May most of them survive Chicago . . .

Last year I saw what seemed like dozens of Hemaris diffinis and H. thysbe moths around one of the butterfly bushes at Perennial Garden. This summer I’m seeing very few — mostly only one at a time. I’ve seen only one giant swallowtail, the first butterfly I noticed there on my way home from the farmers’ market. I haven’t seen one since.

At least I’m seeing monarchs, tiger and black swallowtails, red-spotted purples, several kinds of skipper, and a few hackberry emperors. I’m terrible at identifying trees, but several of the trees look like hackberry trees. The hackberry is to the hackberry emperor what milkweed is to the monarch — sole food for the caterpillar.

On August 11, a very pale hackberry emperor landed on my shirt and stayed until I had to start walking and gently shooed it off.

I say “pale” because hackberry emperors are usually darker.

Last week I was about to walk my bike through the grass from one bush to another when a hackberry emperor landed on my arm. It proceeded to probe about with its proboscis. It went at it for several minutes, even after I started walking again, arm raised in an awkward position. After a few moments it flew off.

Assuming it was sucking up sweat, I looked up the behavior, called “puddling.”

By sipping moisture from mud puddles, butterflies take in salts and minerals from the soil. This behavior is called puddling, and is mostly seen in male butterflies. That’s because males incorporate those extra salts and minerals into their sperm.

When butterflies mate, the nutrients are transferred to the female through the spermatophore. These extra salts and minerals improve the viability of the female’s eggs, increasing the couple’s chances of passing on their genes to another generation.

What could be more charming than knowing your sweat will help produce more hackberry emperors? I may not have children and grandchildren, but I will have butterflies!

On the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore events calendar, the National Park Service refers to “spectacular Miller Woods.” I’ve never gone on the ranger-led hike—it’s probably more than I can handle—but J and I decided to try out “World Listening Day Program and Sound Hike” with the Chicago-based Midwest Society for Acoustic Ecology.

First we had to get there, which isn’t easy with temptations on the way. At a corner close to our destination, we spotted the Miller Beach Farmer’s Market, where we spent time and money. I love open air markets, even when they’re in a small, dusty parking area.

I had no idea where Miller Woods was, but it’s down the street from Miller Bakery Cafe, where we’d gone for dinner a couple of times. It’s a hidden gem. After parking, you walk over a shaded enclosed pedestrian bridge to the Paul H. Douglas1 Nature Center, which has interesting exhibits and helpful young rangers, and, on this day, leftover cookies. I learned a different way to tell frogs and toads apart (frogs have a prominent tympanum).

After checking out the animals (and the cookies), we met Monica from the Midwest Society for Acoustic Ecology at the back exit. Behind us was the Miller Beach neighborhood of Gary, Indiana, with stores, restaurants, gas stations, etc. In front of us was a dunes woodland with ponds and two beaver dams, leading to a beach (we didn’t go that far). I had one of my fleeting moments of feeling like I was stepping out of reality into a magical place, separated by time and space.

We arrived an hour or so before the hike was to end, but Monica and her photographer husband told us only one person had shown up earlier. The idea behind this walk was to be as quiet as possible—a struggle for an extreme extrovert like J—and to listen to the sounds around you, how they change as you move, and so forth. I decided I’d better warn her that both he and I have faulty hearing, partly so she’d know our ears might not pick up every nuance hers did, and partly so she’d know that we might not hear her if she spoke quietly.

Off we went, with her husband well in front of us. Miller Woods is fairly quiet for being in an urban area, and I soon became aware of how much noise I can make walking on stony ground if I barge forward—and, interestingly, that my left leg drags more often than my right. A train, I think Amtrak, rumbled through to our left, which was my first indication of train tracks at Miller Woods. One or two birds called repetitively, although at times and in places the birds were quiet.

At the point where we looped back, we could hear a low rumbling (“groaning,” as Monica described it) to our left. She told us there’s a plant of some kind in that direction.

At another place further on, I imagined I heard a skittering on the ground and spotted this insect. I say “imagined” because there’s no way my damaged hearing could pick up an insect’s exoskeleton or wings on stone.

When we were at a low point, she noted how muted and absorbed sound seemed to be (like sound in snow). At a high point after a steep climb up sand, sounds carried—tree leaves rustling, birds calling, sounds in the distance. I told her about aspens, which to my surprise she didn’t know about.

All this time I was tempted to take photos, but kept them to a minimum—even the sounds of the shutter in the relative quiet seemed too disruptive.

Just as we were reaching the end near the nature center, J and I heard a deep strum from the nearby pond vegetation that our guide hadn’t—most likely an American bullfrog. He strummed a few times before we left.

Inside we talked with Monica, her husband, and an older man with a microphone about their organization, iPhone add-on, aspens, and other topics. We learned Monica and spouse live on the north side of Chicago and had taken the train and a shuttle to Miller Woods; they would have to wait until after 6 p.m. for the next train on a Sunday. Dedication! I felt bad they’d had an audience of only three for all that effort.

I found the young rangers eager to answer questions and chat. When I wandered back to the desk from the restroom, I found the two young men pulling the fronts of their shirts down and looking/pointing. I may have looked at them strangely. “We’re comparing our shirt tans,” one explained.

When he’d heard dinner was next on our agenda, the older man with the microphone suggested we try Captain’s House. The proved to be a charming restaurant in a house with a nautical theme and a seafood focus (and alternatives for the seafood averse like me). Next time we’ll have to choose a bigger table.

Is Miller Woods “spectacular”? I can’t say. It’s not the Grand Canyon, Arches, Yosemite, or Yellowstone. We didn’t see all of Miller Woods—the trail goes out to Lake Michigan. All I can say is it was spectacular to me. Now, if I could spot a Karner blue butterfly there . . .

1 Paul Douglas was the Illinois senator who had worked to establish Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore.

The adventure began with an email from Openlands about “Paddle the Lake Michigan Water Trail” events in the far north suburbs (Ray Bradbury country). JB and I had gone to one of these a couple of years ago in Jackson Park. Wilderness Inquiry owns the canoes, and they bring paddling to people who wouldn’t have much opportunity, like city kids and the disabled (which I am when it comes to getting into and out of a canoe). They had a life preserver large enough for me (impressive!) and were patient with my difficulties.

We paddled around the lagoon, seeing a great blue heron take off from shore at canoe level. It’s a different world from a canoe, where you’re less of an outsider/intruder and more one with the water — even if you can’t swim. You’re almost like a bird yourself, maybe a loon bobbing on the water.

The Jackson Park paddle was cut a little short by choppiness coming into the lagoon from Lake Michigan, but we were out for a while, probably at least 45 minutes, and I wouldn’t have been surprised if some of the kids (and maybe an adult or two) were paddled out. We’re not hardy voyageurs, after all.

On Sunday it took about 30 to 40 minutes longer than it should have to get to Illinois Beach State Park thanks to a 4th of July parade in Waukegan that had closed down an extensive stretch of Rte. 137, which is the only practical way into the park. By then of course I had to find a restroom.

After those preliminaries, a conservation office pointed us toward Openlands’ tent by the lake, but we discovered we should have followed the “free canoe rides” sign pointing mysteriously inland, as it turned out the lake was too choppy for beginner paddling. We hightailed it west across the parking lot and down a service road and found the canoes at a pond by the campground.

We were just in time for the last paddle of the day. Wilderness Inquiry’s largest life jacket still fits me. Yippee! Enough people arrived after us to fill a canoe. I even managed to get in without too much struggle, thanks to the setup. So far, so good.

Just as we were scootching around to balance weight side to side and settling in, it started to rain, slowly at first, but soon with bigger drops coming down faster. That’s okay, they told us. We can go out in the rain as long as there’s not lightning. They asked if anyone wanted out. To all our credit, no one moved (not that I could!) or spoke up. Soon the cloud either moved on or emptied out because the brief downpour ended as abruptly as it had begun.

This pond, which I had not known about, is big enough to paddle but not too big for beginners or small children. We went around it perhaps three times, giving us a chance to practice turning and stopping (JB and I are pretty good at this by now). As we started out, a fish leaped out of the water and fell back before I could get a good look. Our trip leader told us the pond is full of bass. It was also surrounded by male red-winged blackbirds on slightly better behavior than they’d shown earlier in the spring. I mentioned that in Chicago frustrated residents have been known to call the police on the territorial birds. I don’t think there’s such a thing as “wing cuffs.”

Meanwhile, I was keeping an eye on the darkening western sky, even as the east remained bright. We returned to shore, and I got out with some extra time and a helping shoulder to lean on. (I feel pressured because anyone forward of me has to wait for me, although they were patient, too.) We chatted with one of the Wilderness Inquiry guys, who was hoping to go to the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness, then finally left.

As we walked down the service road, we stopped to take a few photos of the flowers and a monarch who was landing selectively on a couple of butterfly weed plants. I still watched the “gathering gloom” and suddenly decided an expedited march to the car might be warranted just as thunder boomed. Moments later the temperature plummeted dramatically from the low to mid 90s. We made it just as the skies opened up with a thicker, more sustained downpour accented by sporadic thunder and lightning. We joined a lot of beachgoers in fleeing the park. What perfect timing all around, despite the late start, the parade detour, the pit stop, and the mini-hike to the pond.

We rewarded ourselves with coffee and a brownie at It’s All Good, but the restaurant we wanted to go to had no power. Plan B was a family Mexican restaurant and so home. My kind of day.

25 March 2018

J. and I headed to the Calumet area, specifically Deadstick Pond near Lake Calumet. There’s no public access I can see, and a fence separates the area around Lake Calumet from the frontage road parallel to I-94, Doty Avenue. Collected against the fence is trash — tons of trash. I envision hordes of high school students and adult volunteers spending a few hours a few weekends cleaning up the accumulated trash along the fences at Lake Calumet and Deadstick Pond. The area seems so little traveled that no one may notice, but it’d be a small step toward restoring a semblance of beauty to the area — as long as it isn’t trashed again.

The Calumet area, for many years the center of Chicago’s steel industry, carries an eerie air of a transition zone. Stony Island, a broad, heavily traveled avenue through Hyde Park, South Shore, and other communities, turns into a two-lane, potholed, unmaintained road flanked by tall grasses, nascent parks like Big Marsh, landfills, and the occasional industrial-style building and parking lot. There’s not a house to be seen, nor any sign of a neighborhood.

Eventually, the avenue that further north boasts restaurants, stores, churches, hospitals, and other urban fixtures dwindles down to a cracked, littered pavement that ends abruptly short of a curve of the Calumet River. Traveling down Stony Island can feel like a ride on a time machine toward a future apocalypse, when industry’s mark is visible but faded, and nature is slowly creeping back through the piles of plastic bags and bottles. It’s like the end and beginning of the world.

As J. carefully navigated the potholes, a few cars and trucks sped past at speed — in a hurry to get to who knows where. We stopped on the roadside at Deadstick Pond and peered through the vegetation and fence for a peek at some ducks bobbing along among gray snags. There may have been swans, or plastic bags masquerading as swans.

Next we found Hegewisch Marsh, where he parked by the rail bridge and we wandered down a rough road parallel to the tracks. Many ducks floated on the open water while their passerine counterparts flitted about the bare trees. Along the way I found a lot of scat, most loaded with fur. The open areas connected by the river, rail lines, streets and bridges, along with wildlife-rich marshes, must be coyote havens. I hoped one was following us with its amber eyes as we tread on its territory.

We stopped at Flatfoot Lake in Beaubien Woods, also off I-94, which roars over the otherwise serene setting.

On a satellite map, Lake Calumet, the largest lake within Chicago, looks artificial. I couldn’t guess its original contours. It’s surrounded by nearly empty, decaying streets, the occasional vast building, the ceaseless noise of a busy interstate, and other trappings of modern dreams. There are other dreams, though. The Lake Calumet Vision Committee has a dream for the Calumet region that includes biking, jogging, paddling, and sailing, along with a trail connecting the Pullman National Monument to the young Big Marsh Park — potentially 500 acres of new habitat. It’s going to take time, and it can’t happen fast enough for me.

Now if we could only do something about the roar of I-94.

Source: Raising Parks and Wetlands from Industrial Sites along Lake Calumet

I don’t see signs about wildlife very often, although this one at Windigo, Isle Royale National Park, warns unsuspecting visitors about the island’s less famous, thieving canine. What do the red foxes of Isle Royale do with the car keys and hiking boots they purloin?

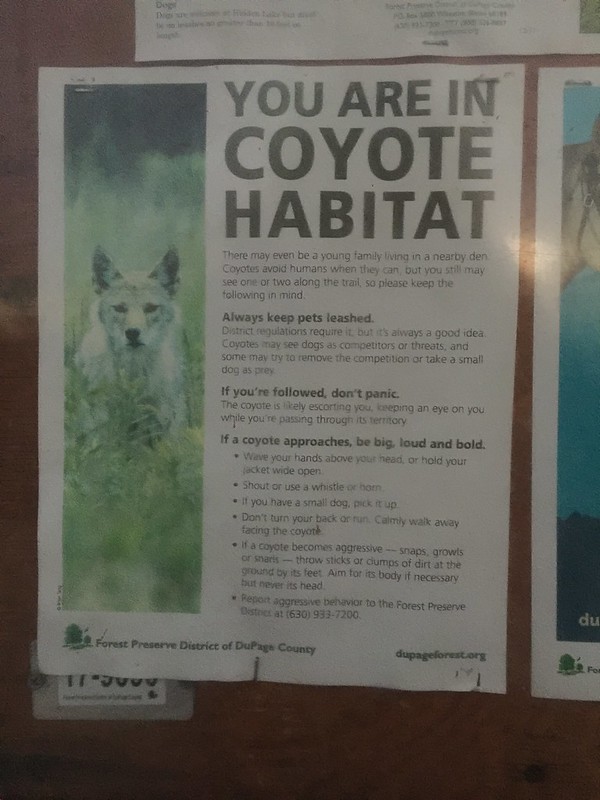

This sign, at Hidden Lake Forest Preserve near Morton Arboretum, exhorts you not to panic if Wild Fido follows you. He’s simply giving you an escort through his domain. If this task makes him snappish, simply throw clumps of dirt at the ground by his feet. I’m having visions of Monty Python and “Confuse-A-Cat.”

Other signs warn you about smaller wildlife, especially the kind that hops aboard. This one, at Michigan’s Grand Mère State Park, tells what to wear to help stave off the dreaded tick. By the time you’re at the park, however, you may not have clothing alternatives handy. The tick shown is terrifyingly big, but the ticks that can share Lyme disease with you may be little larger than a pinhead.

Pro tip: At Shawnee National Forest, which is tick heaven, I thought wearing a hat would keep them off my head at least. Not so. After a delightful morning at Pomona Natural Bridge, I felt movement in my hair and found a couple strutting under my hat on top of my scalp. This is one of those times when baldness would be an advantage.

Located at a town park near Grand Mère, this sign is not so much a warning as a caution. If you aren’t careful and you spread the emerald ash borer, this will happen to your ash trees. I can attest to the lethal behavior of the well-named emerald ash borer—both tall, mature trees in front of The Flamingo, plus the mature tree that shaded my bedroom at 55th and Dorchester, succumbed to these little green scourges.

At Hidden Lake Forest Preserve, we’re told it’s too late to keep out another horror, the dreaded zebra mussel. You can be a hero, however, by cleaning your boat and equipment properly so you don’t transplant them to a body of water where they haven’t taken hold. The use of “infest” is a great touch. It reinforces the nearby “No swimming” sign nicely. Swimming in infested waters just doesn’t appeal to me, even if I could swim.

If you’re about my age, you recall that “only you can prevent forest fires (that aren’t caused by lightning strikes, volcanoes, and other natural hazards). Many parks post the current risk of wildfire danger based on conditions like drought and wind. At Lyman Run State Park in the Pennsylvania Wilds, Smokey Bear can’t seem to make up his mind.

This version of Smokey opted for words instead of visuals, which makes his message less ambiguous (no broken pointer). No doubt that snow on the ground helps to keep risk low.

Taking shape on Stony Island Avenue in the remnant heart of Chicago’s steel industry, Big Marsh Park features a bike park (built on slag too expensive to remove), natural areas, and occasional bald eagle sightings. An enticing hill nearby forms a lovely backdrop for a walk at Big Marsh, which is still in its infancy. When you get closer, however, and read the signs, you learn it’s a steaming, seething landfill that’s being “remediated.” There’s no happily running up and down this slope. How I miss the Industrial Revolution.

It’s not every day you’re warned about lurking unexploded bombs, but for me this was no ordinary day. It was my first visit to Old Fort Niagara in nearly 40 years, which coincided with Memorial Day weekend. Most of the time, the fort is manned by soldiers in 1700s military fashions, but in honor of the holiday other conflicts were represented. I kept my distance from the bomb. Just in case.

This is one of the odder warning signs I’ve seen. I left the chef alone—after all, he works with sharp objects.

Slow down. Chicago is under a budget crunch, but do they send out a lone fireman like this? A lone fireman without a steering wheel? Or arms?

Here’s a warning sign you can ignore. It’s outside Riley’s Railhouse, a train car bed and breakfast in Chesterton, Indiana, that’s a treasure trove of signs.

From the exterior of the car I slept in:

At Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore’s West Beach, it looks like the National Park Service is testing which sign or message is most effective at keeping visitors off the dunes. This one shows bare tootsies with the universal “No” slash, helpfully pointing out the dunes are ours.

A less friendly, sterner, more wordy one admonishes you to “KEEP OFF THE DUNES” and appeals to your desire to “Please help protect and preserve our fragile dune systems!”

At the beach, this slash through a barely visible hiker shuns wordiness (or words) for directness and simplicity without justification or explanation.

It’s sandwiched between even more minimalistic signs with a slash, planted where the dunes start ascending. Don’t. Just don’t.

Years ago when a landfill near my cousin’s house became a Superfund site (just what you want in your backyard), it was surrounded by an electrified fence complete with warning signs. Noticing there were no insulators, I dared to touch it. In this case, however, I’m certain the area behind the fence is dangerous, and this is as far as I got.

Normal weathering or resentment over the weapons message?

Waterfall Glen, a DuPage County Forest Preserve, forms a ring around Argonne National Laboratory, “born out of the University of Chicago’s work on the Manhattan Project in the 1940s.” Naturally, the immediate area around the lab is secured. While I was baffled by this sign about “lock installation” and “any unauthorized lock,” it was the 10 or so locks on the chain that got my attention. Why do people need to add locks to that chain? Why do they need authorization? From whom do they get authorization? Why are unauthorized locks removed? What does it all mean?

Remember when lead was thought to be safe? I don’t, either. This sign is on an old pump at the remnants of an old general store in the western part of Shawnee National Forest.

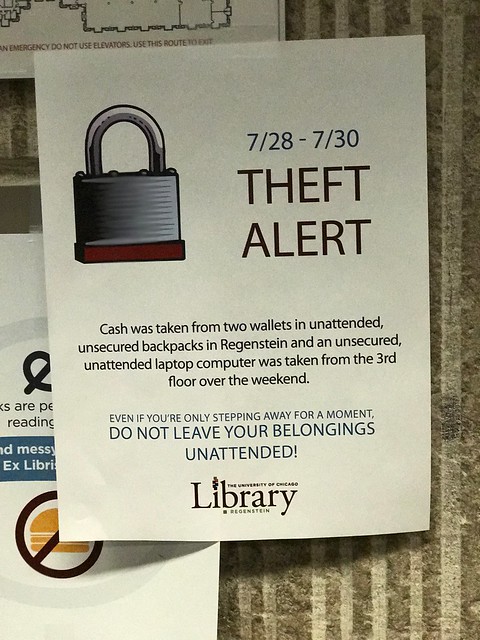

Warning: If you leave expensive stuff lying around, even at an exclusive university, it will walk off. You can bank on it.

RATS? There are RATS in Hyde Park?

More about the Pepperland along with a dream.