Category Archives: Photography

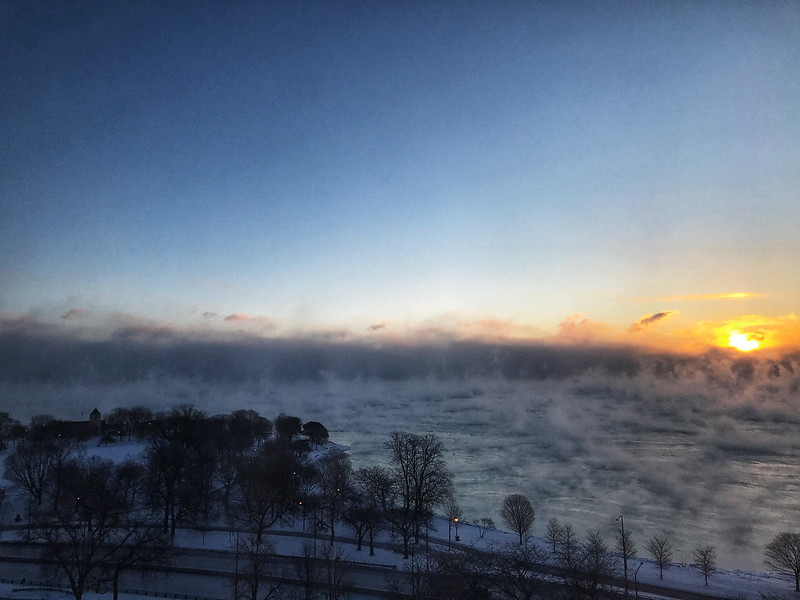

Sea smoke

Flight 93 National Memorial and beyond

On my last full day in Pennsylvania, the 28th, we went to the Flight 93 National Memorial despite the government shutdown. Our route took us down Lincoln Highway, which crosses the United States. It passes through Illinois in the far south suburbs of Chicago. Lincoln Highway reminds me that all of us are connected in some way.

We arrived first at the Tower of Voices, which with the surrounding landscaping are a work in progress. When completed, there will be a chime for each crew member and passenger on Flight 93 — 40 in all. At this time, there were eight if I recall correctly.

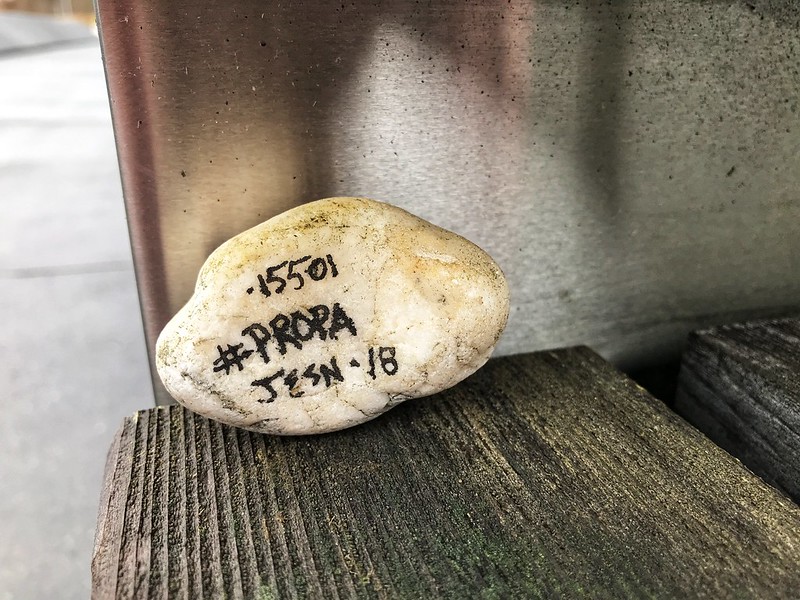

On a bench near the Tower of Voices, we found a “Painted Rock of Pennsylvania.” This is a thing I must look into. I loved this one.

The memorial site is a few miles off, with some farm buildings and wind turbines the main signs of habitation. Before 9/11, the residents of Shanksville and environs could not have imagined visitors from around the world making pilgrimage to their community a half hour south of Johnstown.

The site, which is large, was once a surface mine, stripped of most trees and since replanted. Due to the shutdown, the date, and possibly the gloomy but unseasonably warm weather, there were some but not many people about. We took our time walking to the wall where the names are inscribed, passing the large sandstone boulder that marks the area where the plane came to rest — violently. Someone had left flowers by a few of the names in the wall.

We found another Painted Rock of Pennsylvania on a bench along the way.

I found out via the Facebook hashtag #PROPA that the artist hadn’t expected them to be found until spring. I left both for others to find.

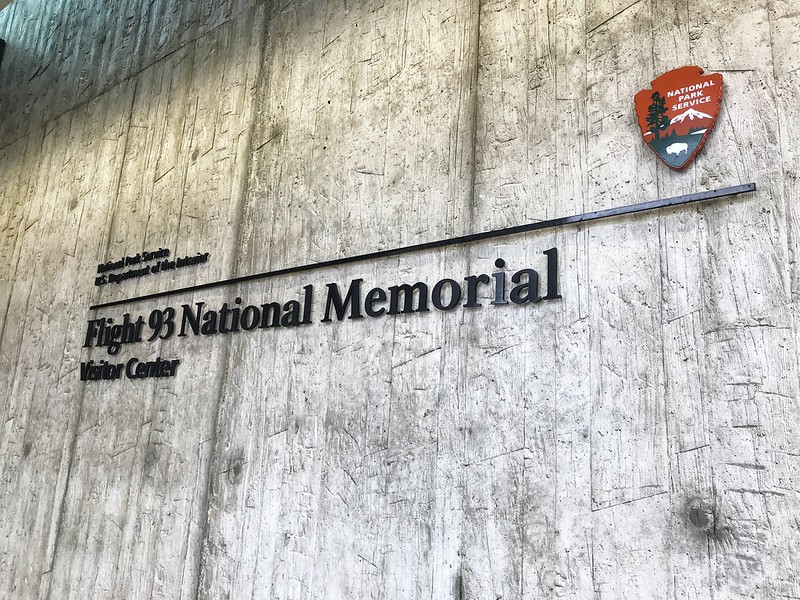

On the way back to the parking lot, we looked at some graphics, then drove to the visitor center. The high walls, marked with the hemlock lines that are the prevailing theme even in the sidewalks, show the path the plane took. In this case, the design’s simplicity adds to the solemnity of the place and inspires the imagination, especially when you remember this horrific event took place on a perfect sunny day in the waning summertime.

The visitor center was closed, of course, but we could see quite a bit through the glass. I wouldn’t have wanted to eavesdrop on those final conversations even if I could have.

On Lincoln Highway, I’d noticed signs for two covered bridges that didn’t seem to be far off — two or three miles, more or less. The first, Glessner Covered Bridge, was down a well-maintained dirt road — not too rutted. The covered bridge is lovely, with a barn on one side and railroad tracks that parallel the stream on the other. The stream is known as either Stony Creek or Stonycreek River. The latter seems redundant. It’s either a river or a creek, but neither is a clearly defined term.

The generous landowner at Glessner covered bridge has posted signs — not the usual “Private,” “Posted,” “Keep Off,” etc,., but signs inviting you to enjoy a little fishing if you’re so minded. I call that right neighborly. It would be a lovely spot to fish in the warmer months.

To get to Trostletown Covered Bridge, we passed Stoystown Auto Wreckers, quite possibly the largest junkyard I’ve ever seen — acres and more acres of junk cars at the bottom of rolling hills. As I recall, the Google Maps capture shows only a portion of the junkyard. Today — unsightly metal carcasses. Yesterday — bucolic covered bridges.

Google Earth image shows the size better.

I’ve read in several places that Trostletown Covered Bridge passes over Stonycreek, or Stony Creek River(?). I use a question mark because Google Maps shows Stony Creek River west of the bridge. I wonder if what we saw is a little offshoot — it doesn’t even appear on Google Maps in blue.

The water, wherever it comes from, doesn’t quite flow freely under Trostletown. It was low and in many places choked with plants and earth. Unlike Glessner Covered Bridge, which is open to cars, Trostletown doesn’t seem to lead anywhere, but ends in a seedy and weedy area. I’d want to plant a butterfly garden with benches there.

I teased my cousin’s wife about driving across the Trostletown Covered Bridge, but she’d already noted it goes nowhere. I drew their attention to another deterrent — a Conestoga wagon blocking the way.

Google Earth shows Trostletown Covered Bridge to your right from the bend in the road.

Trostletown Covered Bridge and the Conestoga wagon are not the only remnants of history here. Kitty corner from the covered bridge the Stoystown American Legion post features a tank and a helicopter positioned to nosedive into the ground. I read elsewhere it’s a Vietnam-era Huey.

On the way to and back, mist smothered and covered what lay in the hollows, often following the meanderings, we thought, of streams and rivers. You can’t quite capture it from a moving vehicle.

Although the day had been gloomy, there was one brief hint of life and color as the sun appeared while making its daily disappearance.

Days like this make leaving harder than it already is.

Night above, day below

World Famous Horseshoe Curve

Horseshoe Curve, 10 minutes outside Altoona, Pennsylvania, is a world-famous National Historic Landmark — so the signs say. It’s not on the beaten track.

When my family used to visit their families in the Altoona/Bellwood area, sometimes we’d make a side trip to Horseshoe Curve. I still have a souvenir calendar from way back when. Note that it was not “World Famous Horseshoe Curve,” but plain old Horseshoe Curve.

I don’t think we paid admission. My dad wouldn’t have paid, or would have paid only a nominal fee, for something as nonessential as a trip to Horseshoe Curve. I remember only that at some point, I’m not sure when, he commented how “overgrown” it’d become, which made it hard to see much.

In September 1988, after I’d been absent for awhile from Pennsylvania, my aunt took me to see it again. The only way to get up then was steps, difficult for her because she’d lost a kneecap to a car accident. You can see why my dad said you couldn’t see much for the trees and brush.

Sliver of Altoona Reservoir in background

In the early 1990s, a visitor center/museum was built, along with a funicular to get up to the top for those who don’t want to or can’t handle the steps. Now there’s an admission charge to see the Curve, which you can go up to only during the posted season and hours. It’s pricey for a family, and there’s no break for Blair County residents.

I’ve seen Horseshoe Curve as a passenger on Amtrak 42 (eastbound) and 43 (westbound), the Pennsylvanian. On this visit I didn’t, however. A freight train accident with a vehicle ahead of the Capitol Limited had made me miss the connection with the eastbound Pennsylvanian, so I’d had to take Greyhound from Pittsburgh to Altoona. On the way back, the Curve is dark when the Pennsylvanian passes at around 5:30 p.m.

The public can’t access Horseshoe Curve during the colder months. When we made a quick stop the day after Christmas, we just looked up. I’ll have to make a trip sometime in late spring, summer, or early fall for a real visit.

Countless trains have passed downhill toward Altoona and points east since Horseshoe Curve was finished in 1854, engineered by J. Edgar Thompson.

Kittanning Run passes under Horseshoe Curve from the north. It’s too bad there’s not a more bucolic fence to protect the public from falling in.

Of course you want to hear that water flowing. The odd thing is . . . I don’t recall anything but the reservoir. You’d think I’d remember hearing or seeing rushing water, but I don’t.

Pushmi-pullyu pairs of black-and-white Norfolk Southern helper engines go back and forth on Horseshoe Curve all day. They’re needed going uphill to pull/push and going downhill to help control speed/brake. You don’t want a long, heavy, fully loaded train speeding downhill around a curve. These two are headed back up the mountain.

It’s Pennsylvania, so you will see coal trains. You can imagine how much they weigh. This one is going downhill east toward Altoona in Logan Valley.

Horseshoe Curve specs

- Curve length: 2,375 feet

- Degree of curvature: 9 degrees; 25 minutes

- Central angle: 220 degrees

- Elevation of lower (east) end: 1,594 feet

- Elevation of upper (west) end: 1,716 feet

- Total elevation climb: 122 feet

- Grade: 1.8 percent (1.8 foot rise per 100 feet)

Wopsononock Mountain, or Wopsy, in Blair County, Pennsylvania

Poor scans of photos taken in 1988 remind me of my dad’s move to Pennsylvania. We had visited family there at least once a year during most of my childhood. As my dad got older, my parents and their family members started to have health issues, people died, and I went to college, we stopped going. By the time I returned to the Altoona area, it seemed strange, yet familiar. What felt oddest was getting there mostly by Amtrak vs. wending our way through southern New York and Pennsylvania on Rte. 219. I felt like a stranger in a strange land, with my mother and many of her family already gone.

Since it was one of my first visits in a long time, my dad’s sister took us to several area attractions. I’d never seen Baker Mansion. The kitchen trough for fresh fish fascinated me. I also recall servants’ quarters at the top of the house. I imagined helpless cooks and maids trapped in the attic while fire raged below, the small windows useless for escape.

We also went to an overlook, but I paid little attention to the name (if it was mentioned) or the location. We didn’t have Google Maps in our pockets for reference 30 years ago. I remember only the loveliness of the view — and that when I went to look over, I slid on shale or gravel and tumbled partway down the hill, my fall slowed, then stopped by a tangle of brush. I laughed.

During my Christmas visit in December 2018, I mentioned the photo to my cousin and his wife, who agreed I must be talking about “Wopsy” (Wopsononock Mountain). It’s directly across from Pinecroft.

From the top of Wopsy, we could see the housing development that replaced the woods on their hill, the old landfill, and perhaps a corner of their house or garage. I realized that the towers I see from their road are where we were standing on Wopsy.

Where once there were wooden fence posts there’s a long, high guardrail covered with grafitti; my cousin feels the area’s not that safe. Devil’s Elbow, which we may or may not have passed, is supposedly haunted by the “White Lady of Wopsononock.” If you don’t believe in the White Lady, you can check out Mindhunter on Netflix about the murder of Betty Jean Shade, whose body was found in an informal trash dump on Wopsy.

What made the death of Betty Jean Shade so different was the violence to her body, and in an effort to determine who killed her, investigators, through the aid of former FBI Agent Dale Frye, who served the Altoona area, turned to the fledgling FBI effort at its Quantico, Va., facility, which was attempting to perfect psychological profiling.

Phil Ray, Altoona Mirror

Betty Jean Shade was found in 1979, nine years before my visit. If I had known that, I don’t think I would have smiled so broadly. But the overlook is still beautiful.

Butterflies and clearwings at Perennial Garden

iPhone photographs of butterflies and clearwings at Perennial Garden, Jackson Park, Chicago, Illinois.

From Amtrak: America the Beautiful, eastern industrial version

Once or twice a year I travel by Amtrak from Chicago’s Union Station — not cross country, just to Altoona, Pennsylvania, and Ann Arbor, Michigan. The Capitol Limited, Pennsylvanian, and Wolverine routes pass through cities, small towns, farmlands, and rusted sections of the Rust Belt. I ride the Wolverine during the day. The journey east on the Capitol Limited is all after dark, but on the return west we are in Indiana when morning dawns.

Steel and power

Amtrak passes through northwest Indiana, where in the late 1800s and early 1900s much of one of the nation’s most diverse ecosystems, the Indiana Dunes, was bulldozed over or carted off (see Hoosier Slide). Shifting Sands: On the Path to Sustainability shows the making of places such as Gary, Indiana, and the long-term costs of short-term gains.

I’m not sure Amtrak goes through Gary, but it stops at Hammond-Whiting, where the view from the train overlooks like an industrial post-apocalypse. That’s the nature of trains — industry and train tracks go together like chips and salsa.

41 40′ 13.20″ N, 87 28′ 7.20″ W

If you were to travel through only northwest Indiana by Amtrak, you’d think the world is made up of industry, utility poles, and casinos. By car, you’d also see billboards for fireworks and adult stores, and countless personal injury and illness attorneys.

41 37′ 11.40″ N, 87 9′ 54.60″ W

41 46′ 37.00″ N, 87 37′ 22.23″ W

41 41′ 47.97″ N, 87 30′ 53.49″ W

On the train, I sleep sporadically. One early morning I woke up to find the train stopped near this structure and garish lighting in Cleveland, Ohio. What could be more representative of industrial eastern America?

41 30′ 17.11″ N, 81 41′ 50.43″ W

Weeds flourish, trees struggle, oily water lies in pools, buildings and train cars rust aggressively, and stuff is strewn everywhere. Human beings seldom appear, although parked cars indicate their presence. In black and white, in color, in summer, in winter, the view is bleak.

A bit of nature

I’m fascinated by where cemeteries appear — sometimes unexpectedly in the woods or at state parks like the Smith cemetery at Kankakee River State Park, Illinois or the Porter Rea Cemetery at Potato Creek State Park, Indiana. This one is on Mineral Springs Road in Indiana, where I94 passes over the train tracks. I couldn’t tell at the time, but it belongs to Augsburg Church, a Lutheran church in Porter. It’s about two miles from Bailly Homestead and Chellberg Farm, which are part of Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, past most of the worst of the industrial areas.

When I see puffy clouds, an eggshell sky, and verdant trees on a June day in Michigan, I can’t wait to get to my destination to soak it all in.

Buildings

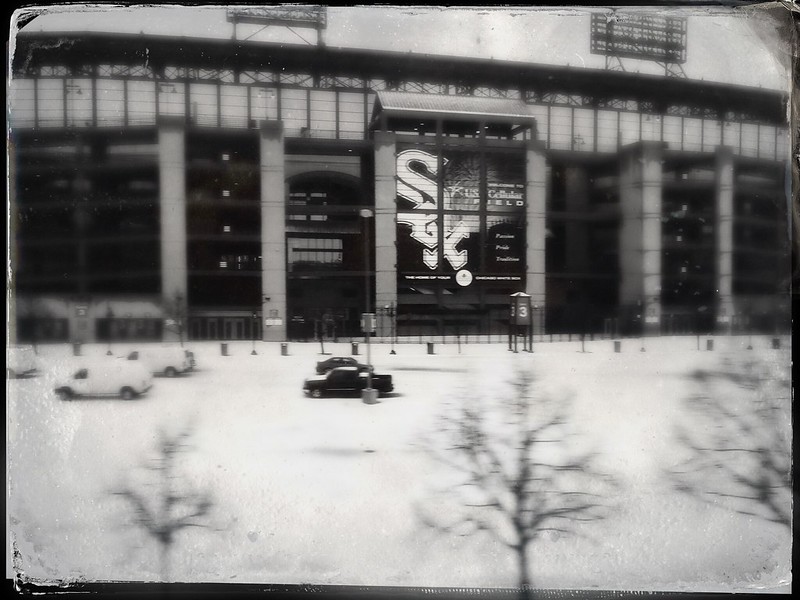

Whether you call it Cellular Field, Guaranteed Rate Field, or Comiskey Park, the home of the White Sox is sometimes a surprise highlight for Amtrak passengers. If you look at the satellite view of the ballpark, though, you won’t believe the number of train tracks to its west. On the starboard side of the train, eastbound Amtrak passengers can enjoy the view of Universal Granite and Marble.

(I don’t like other names)

Apparently a scrapyard in Michigan City, Indiana, has mastered Monty Python’s art of “putting things on top of other things.”

41 42′ 25.80″ N, 86 54′ 34.80″ W

I couldn’t figure out the purpose of this attractive building with cupola, but was surprised to realize later it’s in Michigan City, Indiana, not far from the Old Lighthouse Museum. The Hoosier Slide mentioned above was across from the lighthouse on Trail Creek where it empties into Lake Michigan, near this building. That would have been something to see from an Amtrak train. Now the Hoosier slide site is covered by a NIPSCO coal-fired plant. Progress. Rest in peace, Hoosier Slide. May we not forgot what we have lost and never known.

41 43′ 18.18″ N, 86 54′ 15.75″ W

This wavy fence in Michigan City, Indiana, baffled me. I’ve seen them elsewhere, I think, but I don’t know the purpose other than aesthetic.

41 47′ 48.26″ N, 86 44′ 41.29″ W

There may be millions of nondescript, decaying buildings across the U.S., but I haven’t spotted many more nondescript than this one.

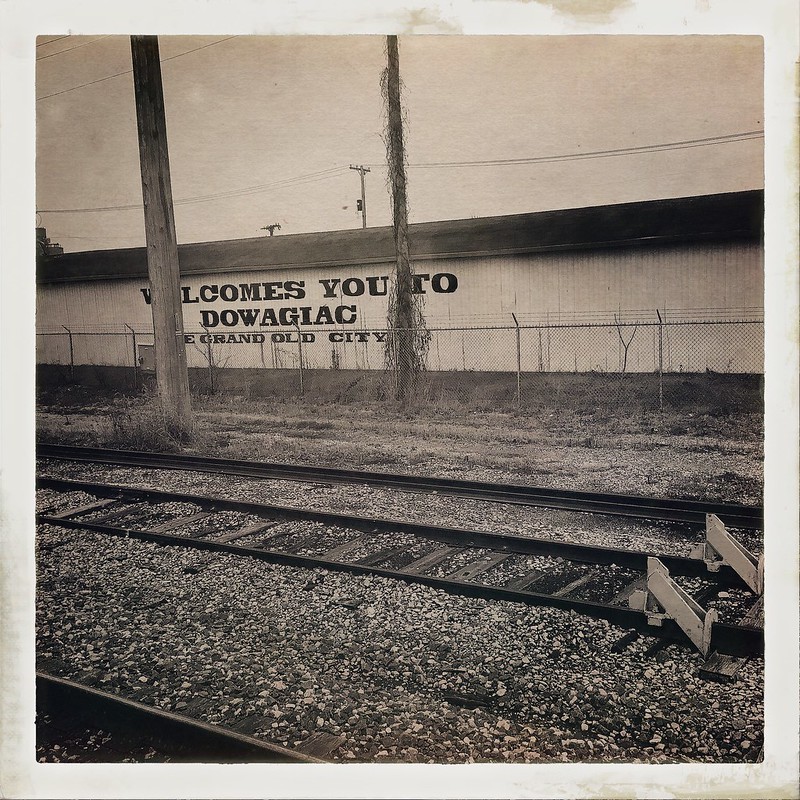

The appearance of this building belies its message that Dowagiac, Michigan, is the “Grand Old City.”

41 58′ 50.28″ N, 86 6′ 34.05″ W

I noticed this long red building on the edge of a small stand of trees in Parma, Michigan, east of Battle Creek. In the satellite view, a dirt road from another building, likely a house, is the only access to it. I’m intrigued by the tall chimney.

42 15′ 36.00″ N, 84 36′ 4.80″ W

With no immediate neighbors, this house, likely part of a tree farm, looks lonelier than it is.

42 15′ 55.80″ N, 84 35′ 5.40″ W

Farm buildings dot the back roads, and rails, of middle America.

42 15′ 51.60″ N, 84 34′ 47.40″ W

Some houses in Pennsylvania towns like Johnstown are spaced closely together, with nearly touching side walls or an alley almost too narrow to squeeze through.

40 20′ 34.94″ N, 78 56′ 14.80″ W

These houses on a hill are farther apart. I wonder if they would have been high enough to escape the Great Flood of 1889—or any since. The area’s geography makes it prone to flooding even without breaking dams.

Johnstown, too, has nondescript commercial buildings.

Stations

Some Amtrak stations, like the modern monstrosity in Ann Arbor, are cold and utilitarian. Next door, Ann Arbor’s former station has been converted into an upscale restaurant, Gandy Dancer.

Old school stations remain in use in Michigan and Indiana.

42 14′ 52.20″ N, 84 23′ 58.80″ W

42 14′ 52.20″ N, 84 23′ 58.80″ W

Often there’s not much to see in the dark, but I spotted the same rotting cars from the EB Capitol Limited. Nearby I found a National New York Central Railroad Museum. If they’re intended to be exhibits, they may use a little work.

Elkhart, Indiana

Coming and Going

The morning Dan Ryan Expressway from Amtrak.

This is what you, and New Buffalo, Michigan, look like to an Amtrak passenger.

As children, we liked to watch for the caboose at the end of long freight trains. When the news pronounced the demise of the caboose, I was distraught. When I can, I watch the scenery recede from the last car of the Pennsylvanian, unimpeded by a caboose, remembering the miles of track and the cities, towns, stations, farms, taverns, fields, rivers, creeks, houses, plants, and stores behind me — and ahead of me on the return.

Finally, all journeys must have an end. Mine passes over the Calumet River through Chicago’s steel history.

“Breathe deep the gathering gloom”

After sitting on Amtrak’s Capitol Limited for several of the wee hours in Cleveland, I realized I was going to miss the Pennsylvanian (7:30 a.m. from Pittsburgh). At the Pittsburgh station I found out a freight train ahead of the Capitol Limited had hit a vehicle.

Amtrak sent us over to Greyhound, so I got to see the scenery from Pittsburgh to Altoona by bus. The skies were gray and bleak.

Here’s the coal-fired Conemaugh Generating Station, which puts out an impressive cloud. It looks thick enough to walk on.

Still, along the way the snow-dusted hills beckon.