Ralph Schirf (dad) — to be continued

Copyright © Diane L. Schirf

Not long after my dad, Ralph Urban Schirf, passed away on July 28, 2001, in Altoona, Pennsylvania, at the age of 88, it occurred to me that I wanted to capture as many memories of him as I could. This is partly so I would remember them and partly so my nieces would learn something of the grandfather they’d never known. Part of this, though, is to help me preserve my childhood — not the details, not necessarily the large events, but simply the feeling of growing up when and where I did. Today, this seems a lifetime away, as though it never happened or happened to someone else.

DOWN ON THE FARM

He was born in central Pennsylvania, the great-grandson of an orphaned German immigrant named Jacob Schirf and the son of Nicholas Schirf, a man who was trying to make a living on a small farm raising chickens. The Schirf genealogy is [no longer] at http://homepage.altoonarail.net/users/kschirf/.

Although the family had 11 children, most of them did not survive to adulthood. One who did, Harold, died at age 21, and suffered from epilepsy. A sister, Marjorie, died in her mid-30s during childbirth. My dad and three sisters were the only survivors after that.

My grandfather apparently relied on my dad to do a lot of the farm work; this, combined with their relatively remote location and the difficulty involved in going to school (they had to walk a mile to a main road through snow and the other elements to get a ride) means that he did not get much in the way of an education. His military papers say he completed eighth grade, but his sisters doubted he’d gotten even that far. Despite that, he was an avid reader, especially of newspapers and publications like wildlife magazines and The Smithsonian. A few years ago during one of my visits to Pennsylvania, I gave him an issue of Natural History, and he excitedly discussed a story about an ancient body found in excellent condition in South America.

His nemesis on the farm was a pair of mules that were his responsibility. As much as he complained about how much trouble they caused him with their stubbornness, at heart he was much fonder of them than he allowed.

There were cats on their farm, and Aunt Marietta would sometimes sneak one or two in because they had not been allowed to have pets. Aunt Thelma said that Dad was permitted to have a dog for a while, but it escaped once and killed some chickens (whether theirs or someone else’s, I’m not sure), and that was the end of that. My older brother Virgil said that Dad mentioned having a pet skunk (minus the scent glands).

At one point in his life he had an accident, but now I can’t remember if it was with the mules or a truck; it was going around a particularly sharp turn at the bottom of a hill. As of a few years ago, there were still people in town who remembered him having that accident as a young man!

He got a job (no small feat at the time) and was saving money at home when the house they were all living in burned down. At that time, no one trusted banks, so he lost his entire savings. One can only imagine the disappointment of that setback for a young man trying to be independent.

ARMY DAYS

In the late 1930s, Dad volunteered to serve in the Army. Eventually, he was stationed in Hawaii, before it was a state and before tourism had cluttered the islands with resorts and traffic. He loved Hawaii, but he developed a lifelong distaste for pineapple.

He was honorably discharged in 1941. Either on his way to or from Hawaii, he spent some time in San Francisco, where the variations in daytime and nighttime temperatures made an impression on him. At the time, soldiers were not allowed to change uniforms, so, depending on the uniform you put on in the morning, you were either hot during the day or cold at night. (My own experience in San Francisco certainly confirms this!) It may have been at this point that he and some buddies drove across Death Valley, with its searing daytime temperatures.

When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and the U.S. declared war, my dad re-enlisted. This time, he was sent with an artillery unit to England. The photos I’ve seen show what look like gigantic bullets aimed at the sky. He seemed pretty fond of England. Again, he was honorably discharged when his tour was over.

Somewhere in his military record, it is mentioned that he went AWOL for a few days. My dad? The man who defined duty It was hard to believe. He never drank, he didn’t gamble, he wasn’t to my knowledge a womanizer, and he was a slave to his obligations. I couldn’t imagine what the story was, so with some trepidation I asked. To my surprise, he told me. He said that the city boys in his unit with were lousy with rifles, and he didn’t want to be in combat with them. He hid for a couple of days until that unit was shipped out so he could ship out with another (presumably better-trained) one. His tone while telling this story was one of disgust that they were so inept.

Once, when my brother Virgil and I were rummaging through a box of old photos, we found a black-and-white WWII photo of a young woman. On the back was a note signed by “Josephine,” and some XXXs and OOOs. My brother and I looked at each other. “Who is this?” we asked. “Let’s see,” Dad said. “Oh, that’s a Scottish nurse I went out with.” (Another significant look exchange.) To our surprise, our reticent father volunteered additional information, which he never did. In an unusually wistful manner, he added, “I would have married her if she’d have had me.” We’ll never know what may have lay behind that revelation. How many such stories will we never know about our parents, and many will our children never discover about us?

CHICAGO

After the war, perhaps a few years later, Dad attended an automotive repair school in Chicago. I am not clear on whether his cousin Bob Gray attended the same school, or if he simply lived in Chicago. (When I knew Bob Gray, he lived in rural Pennsylvania and had many children.) Somewhere in my boxes (still unpacked), I have a photo of Dad with his class. With his thick hair and strong features, he is easily recognizable.

HAMBURG, NEW YORK

I am not sure about the chronology of the following. My dad, discouraged by the work prospects to be had in Altoona, went to Western New York to get a job at the Ford Stamping Plant in Lackawanna, south of Buffalo. In 1952, he, 39, and my mother, 33, were married by a justice of the peace. They lived in a small trailer at Frank’s Trailer Park, 5455 Southwestern Blvd. in Hamburg. It was (and still is, under a different name) located on the corner of Rte. 20 and Rogers Rd. One part consisted of an open field, and behind the trailer park and running along one side of the field were young woods that, in the early 1950s, looked like just a few trees here and there. By 1979, when I left home, they were thick and starting to mature. The owner of the woods, the father of a classmate, was always trying to sell them. In the 1990s, part of them was torn down for a new funeral home on the corner.

VIRGIL RALPH SCHIRF

My brother, Virgil Ralph, was born in 1953. My mother wanted to name him Dwight David, in honor of President Eisenhower, but my dad won — naming him after his cousin, Virgil Strohmeyer, of whom he was tremendously fond. From the first, Virgil has always resembled our mother.

EDEN, NEW YORK

My dad had only one relative who lived nearby, in the farming community of Eden, New York, next to a railroad track. John Nedimyer is younger than my dad, and he and his wife Catherine have seven children, several of whom are around my age. I always enjoyed visits to the Nedimyers because they’re kind, articulate people; I got along well with their girls; and I had childhood crushes on a couple of the younger boys. (I can admit that now.) I can see them now as they were between the ages of 12 and 18. Since moving to Chicago, I have not seen any of them, but do keep in occasional contact with John and Catherine. It’s impossible for me to see their children in middle age, surrounded by their own families. They remain frozen in my memory as youths.

Eden, in those days, was a magical place to me. On the way there, we would pass a cheese chalet (long since closed), which sold imported cheeses, chocolates, beverages, and other items that seemed exotic to someone used to the bland, limited, pre-packaged fare available at chain grocery stories in the 1960s and 70s. The shop itself was interesting, dark, wood lined and filled with such things as cuckoo clocks. I always ended up with several different types of cheese and a hot beverage powder from Switzerland, the name of which I’ve forgotten but I did find it once or twice at my local co-operative in Chicago. I wish I could remember the name. It came in a jar and had a red label.

Another reason to go to Eden was to pick strawberries, usually on Saturday mornings from mid-June through early July (if the weather had not been too wet). My dad’s sisters, Mildred, Thelma, and Marietta, often visited us around that time, and Aunt Marietta (Washington, D.C.) would join us as she seemed to like picking them — and eating them, too. My dad taught me how to pick strawberries — that is, out of courtesy to the grower and to the other pickers, to make sure I picked all the strawberries in the row I had selected that were ready. He and my aunt never had to worry about me eating them while picking (thus cheating the grower) — I didn’t like strawberries. We would come home with all of our wooden quart baskets filled. Then I would help my mother pull the stems off, soak them clean, and crush them with sugar, ready to put on shortcake or ice cream, or to eat alone. My fingers would be sore and stained red for days.

Like Dad, John Nedimyer worked at the Ford Stamping Plant, although I think he was in a different area and held a different kind of job. When my dad was living out what would be his final years at Bellmeade Manor, John would usually stop by during his visits to his own family in Pennsylvania. He told me once several years ago something I’d never known — that he was very grateful to my dad and owed him a lot because my dad had talked him into going to New York for the Ford job. I think he may have even started there before my father did. There was little but low-paying, dead-end jobs in the Altoona area, other than with the railroad. They both felt they ended up better off in New York and at Ford, where even a man with an eighth-grade education like my dad could make a decent living. John seemed to feel that his own relative prosperity — his own home, a few acres of land, and the means to raise seven children — he owed in part to my dad. I feel this was very gracious of him to say.

THE FIFTIES

I don’t know much about my dad’s life in the fifties. Among his papers I did find an accident report referring to an accident that had occurred in Pennsylvania. This stirred some of my cousin Jim Conner’s memories — it was after dark, and they had gone out to buy milk for Virgil, who was quite little. Jim was with them. I think it happened at a corner or intersection, and the other driver was responsible.

When Virgil was growing up, my dad once decided to see how far the car could go on a tank of gas as they were heading home from Pinecroft, Pennsylvania. The answer was, far enough to stall on some railroad tracks just as a train was approaching. He managed to get the car off the tracks in the proverbial nick of time. Virgil doesn’t remember my mother being very happy about this little experiment, and before I knew the story I noticed my dad always seemed careful to keep the tank pretty full, even during the oil crisis of the 1970s.

MYSELF

When my dad was 48 and my mother was 42, I was born — not as common an event for people in their 40s then as it is today. My mother would tell anyone who raised their eyebrows questioningly that I was a mistake, not an accident.

I was actually the answer to my brother’s repeated request for a little sister. Shortly after my arrival, perhaps when he learned that I would require work and get attention, he wanted to send me back, but my mother explained that it does not work that way.

NEW HOME, SWEET HOME

Within a short time of my birth, my parents bought a larger, new trailer, white with yellow trim. It had a high ceiling in the living room and a flip-down room off the living room where the front door was located. It also had a built-in desk with drawers and bookshelves. Mistakenly thinking I would be a social butterfly and debutante, I was assigned the larger of the two smaller bedrooms, partly because the closet was bigger.

FOR THE BIRDS

The west side faced the rest of the trailers in the row and across the street, the east faced the field and part of the woods, the north (rear) faced the woods, and the south (front) faced the road and the field (it was probably at a slight angle). The master bedroom was in the rear, and my dad kept a variety of bird feeders back there, some of them inches from the window so we could watch the woodpeckers, chickadees, nuthatches, titmice, cardinals, etc., close up. Invariably, whoever went into that back bedroom for anything during the day would say in a subdued “shout,” “Come quick! There’s a red cardinal!” Both my parents enjoyed watching birds from these windows.

There was an area in the field next to us where, because of the slate, the grass grew very thinly. One day my dad was walking across it when he saw a killdeer trying to lure him away with the broken-wing routine. He found the nest, which he made sure no one bothered or mowed over.

On rare occasions, I heard whippoorwills calling from the woods, but never saw any. My dad said he saw a great horned owl on top of the light pole next to the trailer. We would occasionally see deer and other wildlife, but the most common were the rabbits who would appear early in the morning and at dusk in the yard to pick through the grass.

ALL CREATURES

Except for the birds, my dad’s attitude toward animals seemed utilitarian, perhaps as the result of his experiences on the farm. We were not allowed to have pets, even fish, although the primary concern given was that we wouldn’t take care of them. Virgil did trap a young rabbit once, but it disappeared from the crate overnight. “The mother probably came and got it,” Dad told me. I believed that at the time, but at some point much later I realised how unlikely that was. I’m certain Dad simply let it return to its freedom. Aside from not wanting any pets, he also knew it was better for the rabbit.

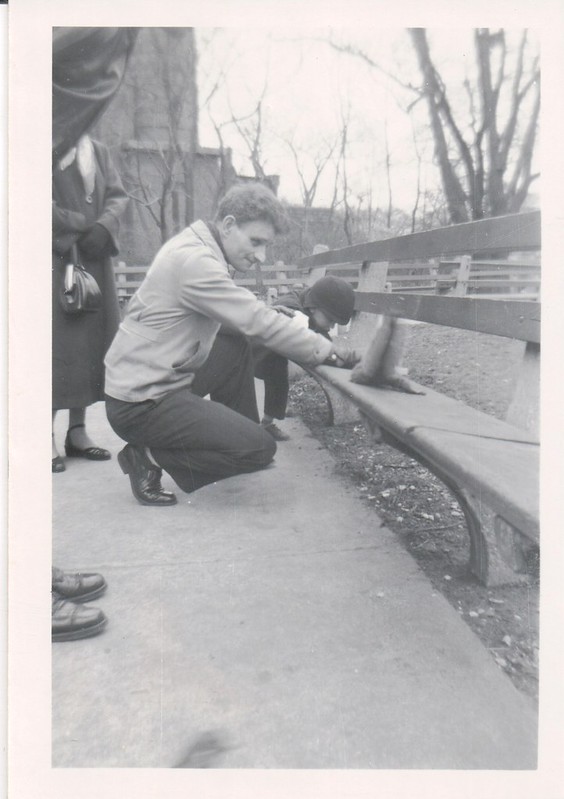

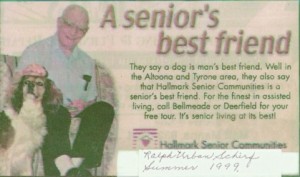

My father liked dogs, like my cousin Jim’s Sweet Pea and, later, his Frank and Jesse. I remember him looking at some old photos of Sweet Pea and saying in wide-eyed amazement, “How white she’s gotten!” A couple of months before he died, we took Frank and Jesse, half-brother poodle mixes, to his room at Bellmeade Manor to see him. His whole face lit up as “The Boys” (then very small) jumped happily all over him with the enthusiasm of puppies. He also made wry faces, which he explained. “I don’t like it when they lick my face!” he said, happily. We noticed that, as excited and rambunctious as they were during their outing, Frank and Jesse and did not nip and bite him like they sometimes did with the rest of us. As Jim’s wife Virginia said, “It’s like they know Uncle Ralph is different and fragile.”

PUDGE

Although my dad seemed to prefer dogs to cats, he was not as hard-nosed about pets as he pretended to be. Shortly after I graduated from college, I scheduled a trip home for the holiday, but was unable to board my cat, Pudge, at the veterinary clinic because of space. The only solution was to bring her with me — a necessity to which he reluctantly agreed. He dug out the round plastic tub I used to put my toys in to be used as a litter box and asked me what kind of food to get for her.

Although he made no moves toward Pudge, he did let her have the run of the trailer, and she seemed to know to stay off places like the kitchen counter. She did get herself into a couple of situations. I took her out on a harness one evening and eventually let her off it, thinking she, being an affectionate cat and seemingly afraid of the outdoors, would stick close to me. Instead, she ran under the trainer and wouldn’t come out. We (I think a friend was there as well) called her and called her, to no avail. We could see her every now and then, and hear her, but she was behind and under all kinds of stuff Dad piled under there (including my old blue swimming pool), so we couldn’t get to her. I think he moved some 2 x 4s lying on the ground under the back end. I don’t remember now how we finally did get her to come out or if we got hold of her and dragged her out, only that it was around dusk and that it was getting dark. I also think she ended up under there twice (apparently, I did not learn my lesson). To my surprise, my dad did not kill me or her.

My bedroom closet at the trailer had sliding doors, and she was persistent about trying to push the second (inner) one over to open it. I tried to jam it over so she wouldn’t be able to get her paw in, but sometimes I forgot. One day she got in and crawled through the pipes in there until she got under the bathtub in the bathroom next door.

I got down on my stomach and could see her eyes peering back at me. I assumed she would come out when she became hungry, thirsty, bored, or tired, or had to pee.

Dad and I went out together for a while and didn’t return home until around 10 or 10:30, which was unusually late for him. No sign of Pudge. I opened the closet door. Sure enough, she was still under the bathtub. She’d been there for at least 8-10 hours! I tried to pull her back through, but her head didn’t seem to fit through on the reverse angle. She appeared to be as confused as I was, and as distressed. By now, it was nearly 11 p.m., by which time Dad was usually in bed.

He suggested getting at her through his bedroom cupboard, the bottom of which was removable. We took a lot of things out of the cupboard, and after a lot of effort and some pain on poor Pudge’s part, I was able to squeeze her between the pipes, although I had to pull her by the front legs to do so. Ouch. It was traumatic for both her and me. I was amazed by my dad’s patience under the circumstances.

One night around 11, I was looking for Pudge and couldn’t find her. I may have heard something; I don’t know, but for some reason I went into my dad’s room to look. He was sitting on the bed next to Pudge, who was lying on it in her favourite position — belly up with legs sprawled. He must not have heard me at first, because he was scratching her tummy and saying something like, “There’s a good kitty.” The moment he realised I was standing there watching, however, an indescribable look came over his face. He withdrew his hand as though he’d been burnt and bellowed, “GET THIS DAMN CAT OFF MY BED!” This is one of my most cherished memories of him — caught in an act of tenderness and denying it.

THE GARDEN OF DAD

On the east side of the trailer, my dad planted a garden parallel to the woods. It wasn’t part of the lot we’d rented, but the owner gave him permission. He also put out a metal glider he had borrowed from a friend and a metal table and umbrella. During warm summer evenings, he and my mother would sit on this glider, rocking back and forth, or he would putter about the garden while she glided. The shadow from the trailer and the trees would grow as the evening progressed.

Dad found a wild rosebush growing in a swampy, low-lying part of the field, so he dug it up and planted it by a trellis at the southwest corner of the garden. During its blooming season (June), I would cut off some of its blooms, put them in a water in one of the rainbow-colored glasses we had, and place it on my dresser because they were beautiful, and I loved the fragrance. I still have one of those iridescent glasses, which is one of my favourite possessions.

My dad grew both vegetables and flowers. His most successful crop was green peppers — they always seemed to turn out well in the slaty soil of Western New York. Tomatoes did not thrive. Once or twice, he found a grotesque caterpillar among them — tomato horn worms. For reasons I didn’t understand, he submerged them in kerosene.

The flowers and other plants included morning glories and four o’clocks (both sensitive to the time of day), zinnias, star phlox, marigolds, tiger lilies, lilies of the valley, black-eyed susans, fire bushes, snow-on-the-mountain, and many others. My favorite, aside from the wild rosebush, were the interactive snapdragons, When you squeeze their sides together, their “mouths” open, and they become tiny, colorful puppets.

When Virgil was in sixth grade, he brought home an ash sapling for Arbor Day, and Dad and he planted it at the southeast corner of the garden. My Arbor Day tree was a silver maple, about which Dad was excited since they are particularly beautiful trees, but it was vandalized. I also grew zinnias in the garden once or twice on my own.

Dad also acquired huge rubber tires that must have come from trucks or construction or farm vehicles. He used these to create smaller flower beds by filling them with soil. One was planted near the glider, while another was arranged in the small yard on the other side of the trailer. I planted a sunflower in this one and was amazed to see how tall and massive it became. I harvested and roasted the seeds, too.

For a while, Dad kept a window box on the trailer hitch and maintained flowers behind a tiny white picket fence in the front yard. He also mowed the grass on both sides of the trailer (as far as to the ash tree/end of the garden on the east side), in front of it, behind it, and even some in the woods. Here, just outside the yard, he planted about seven lilac bushes that disappointed him by never blooming, although I think one or two finally showed a handful of blooms when I was much older.

When Dad was in his late 50s, he decided, perhaps at my mother’s urging, that the garden and flowers were too much work to maintain at his age. At first, for a couple of years, he scaled down the size of the garden and let the rest become overgrown. Then he gave up altogether. I felt truly sad when all that color and life went out of our own lives. It felt like the end.

MANUAL LAWN LABOUR

Dad cut grass with a hand lawn mower. He would take the mower some distance, possibly Silver Creek, to have the blades sharpened, and we would visit a friend who had a boy about my age. I don’t remember anything specific about these visits other than that the area seemed so rural and green and different than I was used to, and the thought of it evokes summer for me in much the same way strawberry picking does. I think the family we visited may have had horses or ponies, although I no longer remember for certain. Dad told me that I liked the boy (Bobby?), that we were great friends, and that the boy and I couldn’t get enough of playing together. The last time we stopped there, he was sick with a contagious childhood disease, and all we could do was to wave to each other. He looked lonely and forlorn.

That was the last I saw of him as a child. Years later, when he was about 18, he and his father dropped in on us. I no longer recognised the shy, playful boy I’d known in the sullen young man dressed like ever other sullen young man of his generation. He did not acknowledge me in that awkward way teenagers have of ignoring anyone once familiar and now strange or undesirable to them. This may have been the first time I realised that children may not live up to their promise — that adolescence and adulthood have a chilling effect on the magic of the imagination and unformed personality, that adolescence, as rebellious as it appears on the surface, is really a process of adapting the individual to conform to group living.

THE BICYCLE

When I was four or five, my dad went to a salvage yard and rescued a girl’s bicycle. He also obtained training wheels and effected repairs, which included painting it sky blue. (Later, he painted it orange — at least, that’s the order I think the colours were in.) After he finished working on it, one evening after supper he got on the too-small frame and rode it around to test it. He would have been about 53 at the time and probably had not been on a bicycle in many years. He rode in circles on the road in front of the trailer just as the light was beginning to fade, while my mother screamed somewhat hysterically, “Ralph! RALPH! You’ll hurt yourself!” He replied nonchalantly, “No, I won’t.” He put his legs (too long for the bicycle) straight out and wore an ear-to-ear grin of carefree glee that I’ll never forget. I’m not sure I’d ever seen him so happy and mischievous — before or since.

POPULAR CULTURE

My parents did not like movies, although I could never obtain a clear understanding of why, other than they were “silly” or ridiculous in some way a waste of time. Since my father watched sitcoms like All in the Family, The Jeffersons, Maude, Good Times, and Sanford & Son, but expressed strong contempt for Star Trek, I could suspect that he preferred television that was contemporary and realistic in its way. He had no use for science fiction and fantasy and even, I suspect, historical drama.

Nothing could keep him from watching wrestling, however. At p.m. every Saturday, after turning the outdoor antennae so it would pick up the signal from Kitchener, Ontario, plant himself on the sofa for a couple of hours of wrestling. My mother would watch from her recliner in the “other room,” a part of the trailer that folded down to add width to the living room.

It was fascinating to watch my dad because he took it all very seriously. He would become oblivious to everything around him and would scowl and growl at the screen. At particularly dramatic moments, he would unconsciously punch his fist and jerk his entirely body forward. I asked him several times if he knew he was doing this, and he said no.

This was not a good time to interrupt with requests for permissions, favors, or money because you could not get his attention except during the breaks. Later, during one of my aunt Marietta’s visits, I noticed her exhibiting similar unconscious behaviour with more open vocalization during a Washington Redskins game and wondered which gene such behaviour lives on.

My dad rooted for the “good guys” — wrestlers who were positioned as honest and rule abiding. He would become disgusted if one of the “bad guys,” like “The Sheik,” would win. He did not seem to believe that wrestling was or could be faked, although it was hard to tell because he was so adept at bluffing.

He especially looked forward to what he considered special treats — “lady” and midget wrestlers. He reacted to them with the same intense seriousness. He also appreciated other anomalies, like “Andre the Giant.” I never learned where he acquired his taste for entertainment wrestling. I know he didn’t like amateur, Olympic-style wrestling, which is regimented and lacks drama and excitement from his perspective.

Today, “professional” wrestling, at least the kind I’ve seen on SPIKE TV, has strayed so far into silliness and outrageousness (wrestlers enacting entire and very phony relationship drams as part of the show) that I suspect even Dad slowly lost interest in it.

Returning to movies: After I had left home, I found out my parents had gone to a theatre to see a movie — Coal Miner’s Daughter with Sissy Spacek. Both of them were country music fans (Loretta Lynn, Glen Campbell, Patsy Cline, Hank Williams, and then performers from the 1970s), so I wasn’t surprised; I was moved at the sweetness of thinking of them going to a movie together. I asked how they had liked it, and the response was either, “It was okay” or “It was good,” either of which would have been high praise.

My father identified strongly with Archie Bunker, although I’m not sure why. They were both blue-collar working men. He liked him as a character and shared his contempt for “hippies” like son-in-law Mike, and perhaps he admired Archie’s outspokenness. I suspect that my dad, like Archie, did not think much of anyone with differing opinions or beliefs. At the same time, he recognised Archie’s own ignorance and foolishness and could laugh at him as much as at “The Meathead.”

Of course, the Archie character was known for his bigotry, particularly toward blacks and Jews. My dad laughed at his outrageous biases, for example, his fear of receiving a blood transfusion from a black man. He recognised the ignorance and illogic of Archie’s prejudices.

BIASES

Thirty or forty years ago, Hamburg was a primarily German-Polish town. There were fewer than a half-dozen Hispanic and black students whom I knew of at my high school of perhaps 1,700. I was sheltered and naive enough not to realise there were racial and ethnic conflicts. I tended to take people as they are. If someone liked me, I would like them back. This is probably how I became friends with a couple of the school’s special education students. It never occurred to me that they were different or that we didn’t have much in common in a conventional sense.

In such an environment, I never had an opportunity to notice whether my parent were or weren’t prejudiced. My dad liked The Jeffersons for the same kinds of reasons he liked All in the Family — Archie Bunker and George Jefferson were representative of a blind, willful ignorance that was humorous in its outlandishness. I think he recognised how much in common Archie and George had in common and that that was where the comic irony lay.

We never discussed race issues until one day, for reasons I dont’ recall, Dad said, “I was raised prejudiced and can’t change. But I never wanted to raise you that way or for you to be like that.” I did not give this much thought then, but now it seems to me a pretty big admission for a man of his generation, education, and background. It was one of the many things that made him seem so different from the other parents I knew.

SUNDAY DINNER

My dad was a man of routine. He did certain things on certain days and at certain times. Although he was a pack rat, collecting junk and reluctant to throw any of it away, he also kept everything in the place he thought it belonged according to his own internal logic.

After he retired, my mother would tell me in a distraught tone how he was criticising everything she did and how he kept rearranging the kitchen. She seemed to think that, if I had been there, he wouldn’t have been so unreasonable and unmanageable. I’m not sure why; he was notoriously stubborn, and I never had any real influence over him.

After my mother died, I’m sure my dad’s life fell into an even more unbroken routine. He never said anything, but he must have been lonely. He was now by himself. He did not have a job to go to, although he attended the occasional union meeting. All of the older people, in the trailer park whom he’d known had moved away or died. His health was deteriorating due to age and diabetes. He’d once dreamed of buying a recreational motor home and seeing the country, like he’d done in his Army days (only in more comfort). This hadn’t appealed to my mother, however, who had been suffering the effects of undiagnosed and untreated Type I diabetes, nor could they have afforded it even if they had been healthy enough. They were a classic example of why dreams should never be delayed.

Just as my dad did not go to movies, he did not dine out. He did not restaurant cooking or prices. Restaurants were a waste of money. The only times we ate out were after band concerts when we went to McDonald’s; when we were driving to Pennsylvania and stopped for lunch on the way; or when we went to Niagara Falls and had lunch at the cafeteria there, which he seemed to like and thought was a good deal. After he was diagnosed with Type II diabetes, he became dogmatic about his diet and would not be adhere to it as strictly as he wanted to at a restaurant.

That’s why I was surprised to learn that, on Sundays, he had made a regular habit of going to a certain restaurant for a pork dinner (noontime). I couldn’t believe that anyone could cook pork to his satisfaction. I was so pleased that he was going out, even by himself, even if only once a week, and enjoying it. Every time I called him, I’d ask him about his last pork dinner there. Once or twice when I visited, I went with him. It made me happy to see him do something so unusual for him and that it made him happy.

POST-LUNCH NAP?

On the last day of one of my visits to Pennsylvania, my cousin Jim drove me to Bellmeade Manor to say goodbye to my dad. As we pulled up, an ambulance was pulling out, but that wasn’t uncommon given the geriatric nature of the population. I asked Jim to pick me up in an hour.

My dad wasn’t in his room, so I looked for him in the lounge. He wasn’t there, either. I’m sure I was very confused. I returned to his room. This time I went in and asked his roommate if he knew where he was. He said Dad hadn’t come back from lunch and that maybe he was in the lounge. I looked again; there was still no Dad. I can’t remember if someone suggested that something had happened and that I should ask at the desk, or if I went there on my own. The woman there said, “Didn’t you see him? He was in that ambulance that left a few minutes ago.”

I called Jim, who came back and took me to the Altoona Hospital emergency room waiting room, where we sat for probably four to six hours or more. The woman at Bellmeade said Dad had not moved after lunch and was unresponsive, so they’d bundled him off to the emergency room. When I finally saw him, he claimed he’d been asleep and that they’d made a fuss over nothing. The ER doctor thought it likely he’d had a TIA. I can’t remember if I went home after all that. I may have, as Dad was grumpy enough to indicate that it was not a life-threatening situation. He was also enjoying the attention of the nurses in his room. They always made a fuss over him. I suspect that it was because of his shock of white hair and his genuinely pleasant smile and his appreciation (despite the grouchy attitude).

To be continued . . .

One year we had sunflowers all along the front of the trailer. They must have been 7 – 8 feet tall by the end of summer with huge sunflowers on top. Sunflower seeds were in that year.

Ah, yes. I pushed that lawn mower many times. Bare footed some times. Green feet and all. Even mowed the horseshoe course.

Thank you very much for this. It was a very kind thing to do for your father, and a nice preservation of history.

Apparently, my father was the reason that your brother was named Virgil–even as he designated me so classically three years before your brother’s birth. However, I had the tale from Dad that he was named Virgil because my Grandfather was part of a group of motorcycle riders (perhaps a gang in 1921) among whom was a Virgil from West Virginia, and that unlucky Virgil met his end playing chicken with a freight train about the same time that my father was born the 8th of 16 to Ann Schirf-Strohmeyer.

I am now working in Washington at State and have lived extended periods overseas. I never used a car until my daughter was due some 16 years ago and always rode motorcycles or bikes, but I went in that direction before learning the story above.

By the bye, I found your blog by entering my name into the Italian search engine “VIRGILIO.” I have found it one of the best for bibliographical searches, and I wanted to know which of my books and articles were still in print. My father, Virgil, died in 2011 at the age of 90. He had nine children, of whom I am the eldest and we are all still living.

Feel free to write and to pass my name to Virgil–Arma virumque cano. Please tell me if any of the stories I think are true are less than really so.

Virgil

Virgil Strohmeyer was my father. He often talked about his cousin Ralph. He died last June 7 (2011) at 90. It was great to read about the Pennsylvania side of the family. My dad had 15 brothers and sisters (2 died before the age of 5). Only my uncle Regis (83) and my aunts, Martha and Billy (92) are still alive. Most of his siblings had 8-10 kids. There are a lot of us in Ohio.

What an interesting story…..brings back memories of visiting you at home, and how nice your parents were. My father is retired from the Ford plant, and also watched Archie Bunker on All in the Family as well…I look forward to more….