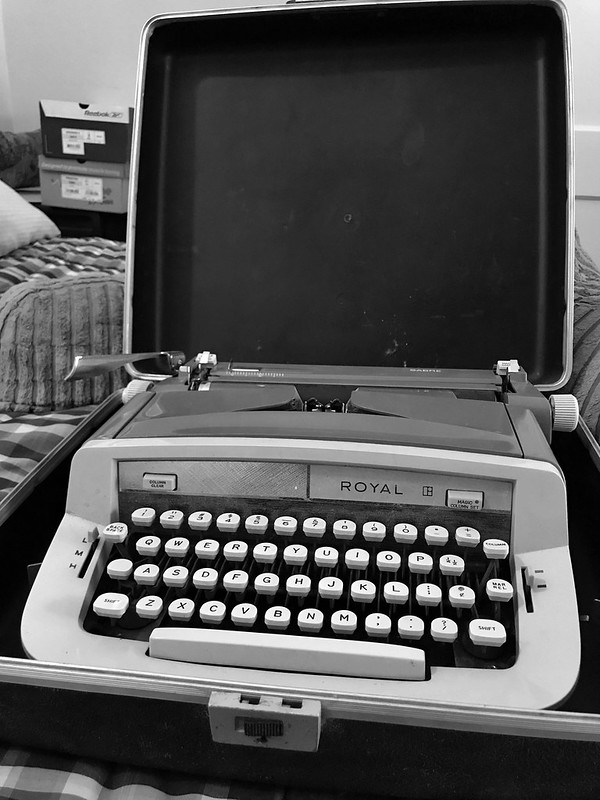

Relics: Portable typewriter, Royal Sabre style

Let’s talk about the relic that’s helped to bring us countless words of wisdom — in more than 144 characters at a time. Yes, today’s relic is the typewriter.

I still have the typewriter that got me through the final years of high school, then college — a Royal Sabre portable, complete with manual (it’s around somewhere, although the key to the typewriter case likely has gone missing). When I moved in 2003, I started to put it outdoors for the neighborhood scavengers, but couldn’t bring myself to go through with it. It was one of the most expensive gifts from my reluctant parents.

Why the Royal Sabre? I don’t remember where we bought it. We would have looked at discount stores like K-mart or perhaps Ames, where I’d picked out my Huffy Superstar 10-speed bicycle. We’d have looked at quality and price. My thrifty dad, who’d turned 16 in 1929, didn’t believe in throwing away good money on poor quality (or generic store brands, unless they’d proven themselves). Because of the store’s nature, there wouldn’t have been much of a selection. I don’t recall the price, but I’d guess about $80 to $90. (Incidentally, this is the price I remember for the Huffy Superstar.)

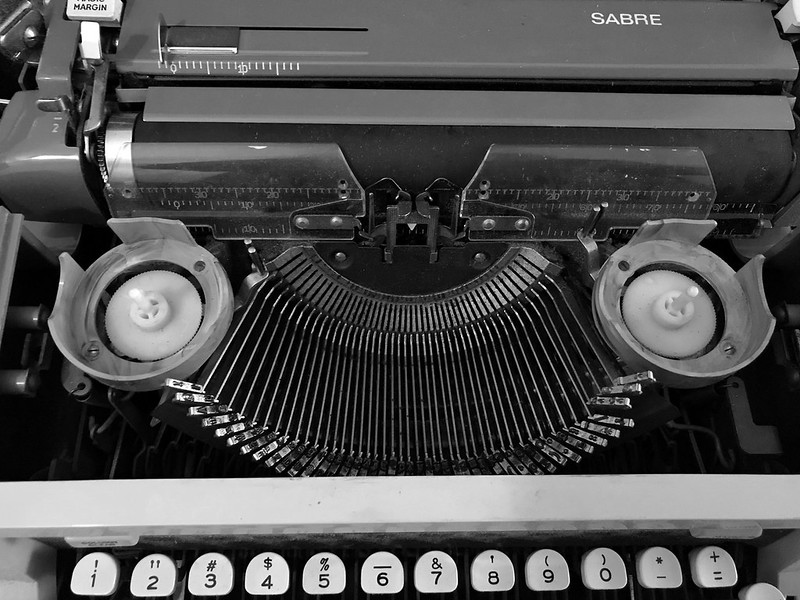

As a portable typewriter, the Royal Sabre was noisy. The keys striking the platen solidly made quite a racket, especially when a poor, erratic like me was in front of the keyboard. My bad habit of typing during the wee hours began in high school, when Mr. Verrault’s papers were due Monday morning. I’m embarrassed now to admit that, in a single-wide, 55-foot-long trailer, on Sunday nights/Monday mornings I was at it until after midnight. Forty years later I can’t tell you how late, but later than suited my early-to-bed, early-to-rise parents. Oddly, I don’t recall much criticism from them for keeping them up. (Of course, my dad could have slept through the Apocalypse.) If he were convinced something was necessary for my education and future independence, my dad would go along as best he could. Of course the procrastination wasn’t necessary — hence my guilty conscience 40 years later!

At college, I found many of my fellow students were more affluent and had electric models, which I considered decadent (I’d told my mother the same thing about electric can openers). I learned I had a fixed number of computer hours per quarter, but playing the text-based Adventure seemed easier than learning to write/type without a program. Although I had a vague idea about computers from Star Trek (for example, oddly computers sound like Nurse Chapel), in practice they were a new and mysterious beast to me.

Then, as now, typing was the last step in the writing process. At 3 a.m., I was writing the paper longhand in pencil on notebook paper in the dorm lounge. At 6 a.m., I was typing the pages slowly on the faithful Royal Sabre. At 9 a.m., I was finishing proofing and marking errors or retyping if needed. At 9:55 a.m. I was running madly up several flights of faux-Gothic stairs (or waiting impatiently for an elevator) to meet a 10 a.m. deadline. By then I would have had some wild hallucinations from fatigue and panic. The Royal Sabre would go back into its hard plastic case, and I would go to bed, too tired and wound up to sleep.

One of my college professors — I don’t recall which — sternly forbade the use of erasable typewriter paper. The finish made it easy to erase mistakes, but it was friendly to neither pen nor pencil. He was so adamant that he would threaten to knock your grade down or refuse the paper if you dared to defy his prohibition. For someone like me — with portable typewriter, subpar typing skills, no correction key, and no budget for different kinds of paper, this seemed excessive.

At some point my dad’s sister Marietta acquired a word processor, and several years after college so did I — a Smith-Corona. It had some built-in storage and some kind of external storage. When I first got it, I spent a happy afternoon playing with the different setups and type wheels, and practicing my typing speed. Suddenly it was dark, and I realized hours had passed while I was blissfully unaware. I used the Smith-Corona for resumés (for all the good that did me) and some correspondence. I’m not sure how I used it, just that it mostly supplanted the Royal Sabre. I don’t think I used it much because it was large and heavy, and I was lazy about getting it out and setting it up. It was also hard to write and edit on the three-line(?) screen.

When it was in semi-regular use, the Royal Sabre never needed repair that I recall. Help was hand nearby, however, if required. A-Active (named to appear at or near the top of telephone directory listings — another relic) Business Machines operated in Hyde Park, first on 57th Street, then at 1633 East 55th, where I remember passing it. I never went in, but the ancient Underwood(?) in the window would catch my eye. The last ad I could find in the Hyde Park Herald for A-Active is dated July 6, 1994 — which was probably about the time I brought home my first computer, a Macintosh Classic II borrowed from work.

The Classic was followed by a series of Apple laptops, and the Smith-Corona word processor faded from favor as I was sucked into eWorld and America Online. When I moved in 2003, I debated with myself over keeping the Smith Corona. Unlike the Royal Sabre, it ended up in the alley, its fate to be forever unknown to me.

In a previous, early work life, sometimes I used a typewriter, likely an IBM Selectric model. When the proofing business was slow, I might help with filling out forms. If I remember right, one or two typewriters had been dedicated to and set up for this task. I don’t recall details (probably to preserve my emotional health), but I’m sure it was a lot of fun to line up everything and hit the magic correction key when the mind or finger slipped as they often did, or start over if things went way south — as they often did. I’m sure I saw the correction key as a technological marvel. I’m pretty sure computerization and automation of forms became big business as soon as introduced.

Every now and then (more then than now), I play with Hanxwriter, a typewrite simulator for Apple devices inspired by actor Tom Hanks. If you want to spend more money, you can “buy” typewriters from the “Signature Collection,” like Hanx Prime Select, Hanx 707 (the closest to the Royal Sabre’s shower stall green), Hanx Golden Touch, Hanx Del Sol, Hanx Electrix, or Hanx Matterhorn. Despite the “now and then” above, I finally bought all. Hanxwriter can save documents as PDFs only, not text — so, like typewritten pages, Hanxwriter pages are not easily edited. There’s something amusing about that.

The Royal Sabre weighs more than even heavy laptops, and from the start I thought the handle on the case was too flimsy for the weight. It’s stood the test of time, however, and as far as I know the typewriter would still work with a fresh ribbon. Surprisingly, ribbons are available for many typewriters, including the Royal Sabre. I tell myself that someday I’m going to get one and try out my computer-improved typing skills, although I doubt they’re better on a machine where you have to depress each key with an impressive force — hence the beauty of those “decadent” IBM Selectrics. Someday.

dreamer

dreamer  thinker

thinker

If you haven’t seen it — I would recommend the documentary California Typewriter (dir. Doug Nichol, 2017).Tom Hanks is among the typists featured.