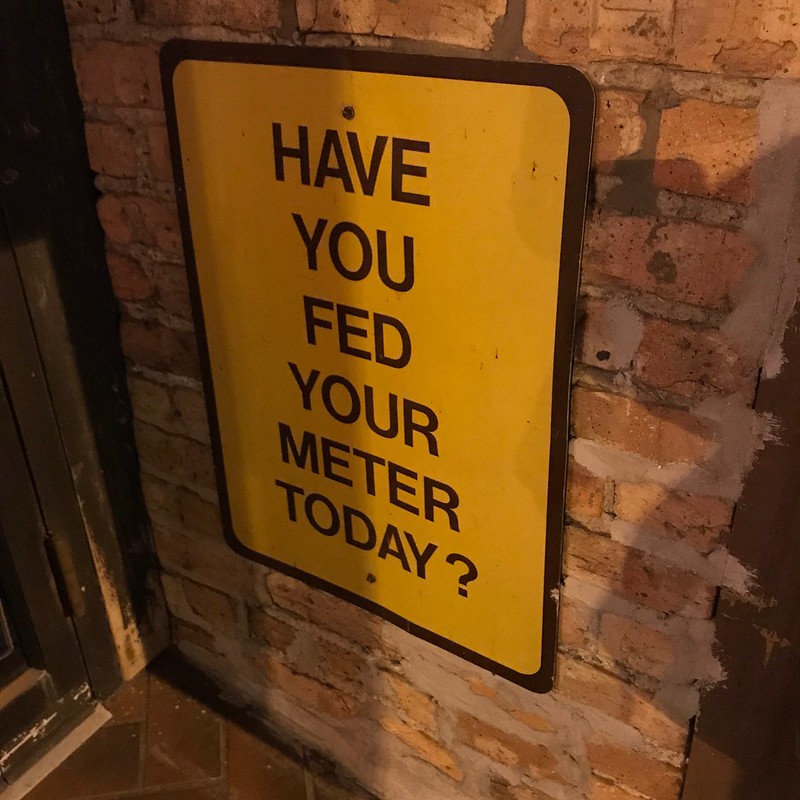

Do you remember “lovely Rita, meter maid”? If your name is Rita, you may never forgive the Beatles. If you remember the Beatles’ heyday, you may recall parking meters.

Once upon a time in Chicago (and today in many suburbs), you put coins into a metal contraption embedded in the sidewalk to pay for parking. The challenge was to have enough quarters and not to over- or underpay. You might have to dash outside in the middle of a restaurant meal or movie to check on the meter or add coins.

To keep you honest, uniformed “meter maids” patrolled the meters, writing a ticket to place on each car next to a meter with a red “expired” flag. Alternatively, she might listen to your sob story about how you were just leaving, etc.

If you were running a quick errand and were lucky, you might find a meter with time left on it. No matter your financial lot in life, whether rich or poor, finding an unexpired meter made you feel great. You saved a quarter or 50 cents!

In Chicago, the traditional parking meters by each parking spot are long gone. Instead, you pay at a “pay box” on the block, usually with a credit or debit card.

If you have a smartphone, there’s an app for that. This lets you avoid the walk to the pay box, alerts you when time is almost up, and allows you to add time if needed.

Parking meters are relics, along with the term “meter maid.” “Parking enforcement officer” sounds better, that is, if you’re not parked illegally.

This is the only parking meter left near me, the only one of several that lined the block.

I haven’t seen a cyclist use this parking-meter-turned-bicycle-post. Yet.