Those bits of blue sky tantalize, don’t they?

Followed this afternoon by a hint of a rainbow.

Last year I saw what seemed like dozens of Hemaris diffinis and H. thysbe moths around one of the butterfly bushes at Perennial Garden. This summer I’m seeing very few — mostly only one at a time. I’ve seen only one giant swallowtail, the first butterfly I noticed there on my way home from the farmers’ market. I haven’t seen one since.

At least I’m seeing monarchs, tiger and black swallowtails, red-spotted purples, several kinds of skipper, and a few hackberry emperors. I’m terrible at identifying trees, but several of the trees look like hackberry trees. The hackberry is to the hackberry emperor what milkweed is to the monarch — sole food for the caterpillar.

On August 11, a very pale hackberry emperor landed on my shirt and stayed until I had to start walking and gently shooed it off.

I say “pale” because hackberry emperors are usually darker.

Last week I was about to walk my bike through the grass from one bush to another when a hackberry emperor landed on my arm. It proceeded to probe about with its proboscis. It went at it for several minutes, even after I started walking again, arm raised in an awkward position. After a few moments it flew off.

Assuming it was sucking up sweat, I looked up the behavior, called “puddling.”

By sipping moisture from mud puddles, butterflies take in salts and minerals from the soil. This behavior is called puddling, and is mostly seen in male butterflies. That’s because males incorporate those extra salts and minerals into their sperm.

When butterflies mate, the nutrients are transferred to the female through the spermatophore. These extra salts and minerals improve the viability of the female’s eggs, increasing the couple’s chances of passing on their genes to another generation.

What could be more charming than knowing your sweat will help produce more hackberry emperors? I may not have children and grandchildren, but I will have butterflies!

I don’t see signs about wildlife very often, although this one at Windigo, Isle Royale National Park, warns unsuspecting visitors about the island’s less famous, thieving canine. What do the red foxes of Isle Royale do with the car keys and hiking boots they purloin?

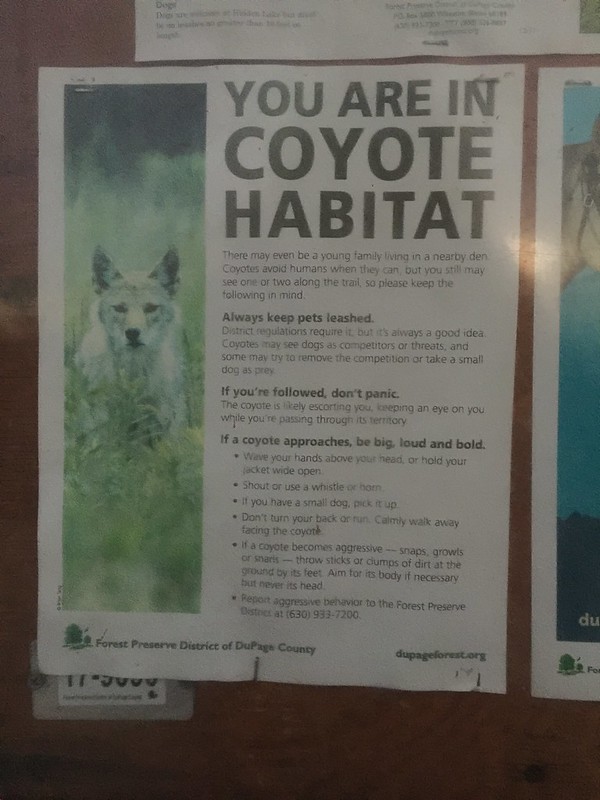

This sign, at Hidden Lake Forest Preserve near Morton Arboretum, exhorts you not to panic if Wild Fido follows you. He’s simply giving you an escort through his domain. If this task makes him snappish, simply throw clumps of dirt at the ground by his feet. I’m having visions of Monty Python and “Confuse-A-Cat.”

Other signs warn you about smaller wildlife, especially the kind that hops aboard. This one, at Michigan’s Grand Mère State Park, tells what to wear to help stave off the dreaded tick. By the time you’re at the park, however, you may not have clothing alternatives handy. The tick shown is terrifyingly big, but the ticks that can share Lyme disease with you may be little larger than a pinhead.

Pro tip: At Shawnee National Forest, which is tick heaven, I thought wearing a hat would keep them off my head at least. Not so. After a delightful morning at Pomona Natural Bridge, I felt movement in my hair and found a couple strutting under my hat on top of my scalp. This is one of those times when baldness would be an advantage.

Located at a town park near Grand Mère, this sign is not so much a warning as a caution. If you aren’t careful and you spread the emerald ash borer, this will happen to your ash trees. I can attest to the lethal behavior of the well-named emerald ash borer—both tall, mature trees in front of The Flamingo, plus the mature tree that shaded my bedroom at 55th and Dorchester, succumbed to these little green scourges.

At Hidden Lake Forest Preserve, we’re told it’s too late to keep out another horror, the dreaded zebra mussel. You can be a hero, however, by cleaning your boat and equipment properly so you don’t transplant them to a body of water where they haven’t taken hold. The use of “infest” is a great touch. It reinforces the nearby “No swimming” sign nicely. Swimming in infested waters just doesn’t appeal to me, even if I could swim.

If you’re about my age, you recall that “only you can prevent forest fires (that aren’t caused by lightning strikes, volcanoes, and other natural hazards). Many parks post the current risk of wildfire danger based on conditions like drought and wind. At Lyman Run State Park in the Pennsylvania Wilds, Smokey Bear can’t seem to make up his mind.

This version of Smokey opted for words instead of visuals, which makes his message less ambiguous (no broken pointer). No doubt that snow on the ground helps to keep risk low.

Taking shape on Stony Island Avenue in the remnant heart of Chicago’s steel industry, Big Marsh Park features a bike park (built on slag too expensive to remove), natural areas, and occasional bald eagle sightings. An enticing hill nearby forms a lovely backdrop for a walk at Big Marsh, which is still in its infancy. When you get closer, however, and read the signs, you learn it’s a steaming, seething landfill that’s being “remediated.” There’s no happily running up and down this slope. How I miss the Industrial Revolution.

It’s not every day you’re warned about lurking unexploded bombs, but for me this was no ordinary day. It was my first visit to Old Fort Niagara in nearly 40 years, which coincided with Memorial Day weekend. Most of the time, the fort is manned by soldiers in 1700s military fashions, but in honor of the holiday other conflicts were represented. I kept my distance from the bomb. Just in case.

This is one of the odder warning signs I’ve seen. I left the chef alone—after all, he works with sharp objects.

Slow down. Chicago is under a budget crunch, but do they send out a lone fireman like this? A lone fireman without a steering wheel? Or arms?

Here’s a warning sign you can ignore. It’s outside Riley’s Railhouse, a train car bed and breakfast in Chesterton, Indiana, that’s a treasure trove of signs.

From the exterior of the car I slept in:

At Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore’s West Beach, it looks like the National Park Service is testing which sign or message is most effective at keeping visitors off the dunes. This one shows bare tootsies with the universal “No” slash, helpfully pointing out the dunes are ours.

A less friendly, sterner, more wordy one admonishes you to “KEEP OFF THE DUNES” and appeals to your desire to “Please help protect and preserve our fragile dune systems!”

At the beach, this slash through a barely visible hiker shuns wordiness (or words) for directness and simplicity without justification or explanation.

It’s sandwiched between even more minimalistic signs with a slash, planted where the dunes start ascending. Don’t. Just don’t.

Years ago when a landfill near my cousin’s house became a Superfund site (just what you want in your backyard), it was surrounded by an electrified fence complete with warning signs. Noticing there were no insulators, I dared to touch it. In this case, however, I’m certain the area behind the fence is dangerous, and this is as far as I got.

Normal weathering or resentment over the weapons message?

Waterfall Glen, a DuPage County Forest Preserve, forms a ring around Argonne National Laboratory, “born out of the University of Chicago’s work on the Manhattan Project in the 1940s.” Naturally, the immediate area around the lab is secured. While I was baffled by this sign about “lock installation” and “any unauthorized lock,” it was the 10 or so locks on the chain that got my attention. Why do people need to add locks to that chain? Why do they need authorization? From whom do they get authorization? Why are unauthorized locks removed? What does it all mean?

Remember when lead was thought to be safe? I don’t, either. This sign is on an old pump at the remnants of an old general store in the western part of Shawnee National Forest.

Warning: If you leave expensive stuff lying around, even at an exclusive university, it will walk off. You can bank on it.

RATS? There are RATS in Hyde Park?

More about the Pepperland along with a dream.

On Saturday, I witnessed a murder.

The Hemaris moths are gone (presumed dead), and all that seemed to be left are the skippers and an occasional monarch. On Saturday, though, a hungry painted lady appeared. I spent an hour or more trying to take photos of this favorite of mine, but I’ve noticed they tend to turn their wide rumps toward me. I try not to take this personally, nor the apparent glare of the skipper that landed on my finger as I raised the phone.

At some point after the painted lady landed on an upper branch, I noticed it beating its wings furiously. I looked and could see only a bit of yellow-green against the purple flowers, but the painted lady seemed stuck. I broke the sprig off with the butterfly still attached. The poor thing went still, its poor legs curled up. I discovered the yellow-green thing had legs. I later decided it was a kind of well-named “ambush bug” — a tiny but formidable garden predator that doesn’t discriminate between pests and pollinators. Or a crab spider.1

This was one of the few times I’ve interfered with nature — something I’d normally not do and would not recommend. I can only plead that I was distraught over being deprived of my colorful little friend. I was reminded that the butterfly bush, so full of life in August, when dozens of moths, butterflies, and bees flitted about, can also be full of death. I have complicated feelings about the murder (anthropomorphism) of my new painted lady friend, but I won’t go into them here.

This painted lady appeared on Tuesday to console me (I’d taken the day off). In return, I tried to scout the remaining blossoms for lurking killers.

Now, on this last full day of summer, the one creature I saw, a painted lady, flew off when I approached and didn’t return. Another plant down the path that was crawling with a variety of bees only a couple of weeks ago is nearly motionless, with only a few stragglers lethargically tapping into its flowers. There wasn’t even the chatter of birds to relieve the loneliness of the garden past its seasonal prime.

And so summer ends and autumn begins.

1 I’ve seen crab spiders since at Perennial Garden, usually killing skipper butterflies, never Japanese beetles.