Tag Archives: Indiana

Amtrak in Indiana via Lightt, part 1

Lightt was a short-lived video app I still miss. I didn’t have time to master it but I liked some of its effects. This video and a few others demonstrate motion parallax, which I had to look up after I noticed it.

Hipstamatic series 1: Buildings

Interstate Inn, Gary, Indiana

This isn’t the first time the sign for the Interstate Inn has captured my attention. The decrepit sign, with “Restaurant,” beckons you to a building that persists in a half state — still standing but open.

According to Lost Indiana, it was once a Holiday Inn strategically placed to lure travelers on Dunes Highway. To me it’s a metaphor for most of the works of man — a short productive existence followed by a long deterioration haunted by aging, fading memories. It’s like an example of Life After People, only the people haven’t died, just given up.

And now that I’ve seen the Doctor Who episode “Blink,” when I see the Interstate Inn, which is not unlike the fictional “Wester Drumlins,” I’ll think of this bit of dialogue:

Sally Sparrow:

I love old things. They make me feel sad.

Kathy Nightingale:

What’s good about sad?

Sally Sparrow:

It’s happy for deep people.

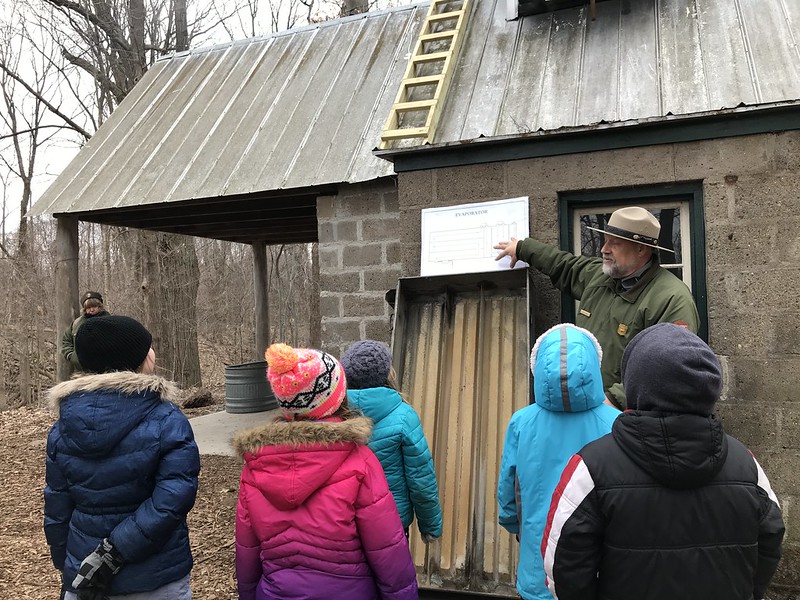

Maple Sugar Time at Chellberg Farm, March 2, 2019

Note the date — 2 March 2019, the first Maple Sugar Time held at the newly designated Indiana Dunes National Park. No doubt it will be years before the signs are replaced.

As I’ve probably said before, Maple Sugar Time brings back one of the few bits of childhood I remember, if vaguely. My class — second grade? — made a field trip to a maple sugar farm (sugar bush) in March, I assume. I wish I knew where, but I’d guess it was owned by the family of a classmate. The world is enormous to a seven-year-old, so I remember it as far away and magical.

The day was dreary and foggy. Dense clouds of fog everywhere at ground level. Or maybe I’m confusing the outdoor world with the sugar shack, where the steam rose in clouds from the boiling sap. I’ll never know for certain. In a world before smartphone cameras we weren’t able to preserve even marvelous moments except in our faulty, failing brains.

I was given a piece of maple sugar candy to try. LOVE. Much better than plain white baking sugar or sugar cubes — some ineffable, ephemeral quality beyond mere sweetness. My mother must have given me some money because I bought a tiny bag of the precious maple leaf-shaped goodness. Even now, when my “allowance” is more substantial and all my own, I look upon maple sugar candy as a rare luxury.

Perhaps the other high point was the draft horses snorting steam into the fog. We may have gone on a wagon ride. If such a thing makes me happy today, imagine how it thrilled me 50 years ago?

Back to present-day Indiana. J and I indulged in our traditional start to Maple Sugar Time — the Chesterton Lions Club pancake-and-sausage breakfast served in a vinyl-sided tent that keeps out some of the cold and breezes. It’s like the year’s first picnic.

Our timing was perfect. We finished our 2 p.m. “breakfast” and found Ranger Bill with a group at the Maple Sugar Trail, ready to go. The hike covers how to identify sugar maples, and I learned the box elder is a maple.

We walked through the various eras of maple sugar making, from hot rocks to metal pots to Chellberg Farm’s sugar shack to more modern methods. As many times as I’ve been to this event, I’d never gone inside the sugar shack. While an impressive amount of steam arose inside (welcome shelter after the cold!), it came from boiling water. Current daytime temperatures are too cold for maple sugar sap to run. Maybe next week — current forecast is for temperatures in the low 40s. But the forecast changes every day.

The walk ended up at the Chellberg farmhouse. Since the building that formerly housed the store has been covered to an employee/volunteer center, the maple goods were for sale in the entry room. Yes, I did buy maple syrup, maple cream, and of course the luxury of my childhood, leaf-shaped maple sugar candy. In another room, we picked up a Dare maple cream cookie. They’re not just for the kids.

Outside we found Belgian draft geldings Dusty (2,450 pounds) and Mitch (2,350 pounds). Dusty left horse slobber all over my hand and bag. When a girl and her brother stood by him for a photo, he started to groom her hair. A little disgusted, she shoved her brother into her former spot. “That won’t help,” the volunteer said. “He’ll just reach right around him.” On cue, Dusty did just that. He wasn’t licking only people. Between visitors, he gave Mitch’s neck some good grooming strokes.

We said goodby to Dusty and Mitch and chickens and headed to Indiana Dunes State Park so I could get a yearly pass and because the beach is gorgeous (and less crowded) on a cold March afternoon. We walked around, but not on the shelf ice. It seems someone finds out the hard way every year that the sign isn’t there for decoration.

We tried the Speakeasy at Spring House Inn, but at this time they don’t serve meals so off we went to Chesterton’s Villa Nova to warm up on Italian cuisine (and add back any calories we may have burned off).

From Amtrak: America the Beautiful, eastern industrial version

Once or twice a year I travel by Amtrak from Chicago’s Union Station — not cross country, just to Altoona, Pennsylvania, and Ann Arbor, Michigan. The Capitol Limited, Pennsylvanian, and Wolverine routes pass through cities, small towns, farmlands, and rusted sections of the Rust Belt. I ride the Wolverine during the day. The journey east on the Capitol Limited is all after dark, but on the return west we are in Indiana when morning dawns.

Steel and power

Amtrak passes through northwest Indiana, where in the late 1800s and early 1900s much of one of the nation’s most diverse ecosystems, the Indiana Dunes, was bulldozed over or carted off (see Hoosier Slide). Shifting Sands: On the Path to Sustainability shows the making of places such as Gary, Indiana, and the long-term costs of short-term gains.

I’m not sure Amtrak goes through Gary, but it stops at Hammond-Whiting, where the view from the train overlooks like an industrial post-apocalypse. That’s the nature of trains — industry and train tracks go together like chips and salsa.

41 40′ 13.20″ N, 87 28′ 7.20″ W

If you were to travel through only northwest Indiana by Amtrak, you’d think the world is made up of industry, utility poles, and casinos. By car, you’d also see billboards for fireworks and adult stores, and countless personal injury and illness attorneys.

41 37′ 11.40″ N, 87 9′ 54.60″ W

41 46′ 37.00″ N, 87 37′ 22.23″ W

41 41′ 47.97″ N, 87 30′ 53.49″ W

On the train, I sleep sporadically. One early morning I woke up to find the train stopped near this structure and garish lighting in Cleveland, Ohio. What could be more representative of industrial eastern America?

41 30′ 17.11″ N, 81 41′ 50.43″ W

Weeds flourish, trees struggle, oily water lies in pools, buildings and train cars rust aggressively, and stuff is strewn everywhere. Human beings seldom appear, although parked cars indicate their presence. In black and white, in color, in summer, in winter, the view is bleak.

A bit of nature

I’m fascinated by where cemeteries appear — sometimes unexpectedly in the woods or at state parks like the Smith cemetery at Kankakee River State Park, Illinois or the Porter Rea Cemetery at Potato Creek State Park, Indiana. This one is on Mineral Springs Road in Indiana, where I94 passes over the train tracks. I couldn’t tell at the time, but it belongs to Augsburg Church, a Lutheran church in Porter. It’s about two miles from Bailly Homestead and Chellberg Farm, which are part of Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, past most of the worst of the industrial areas.

When I see puffy clouds, an eggshell sky, and verdant trees on a June day in Michigan, I can’t wait to get to my destination to soak it all in.

Buildings

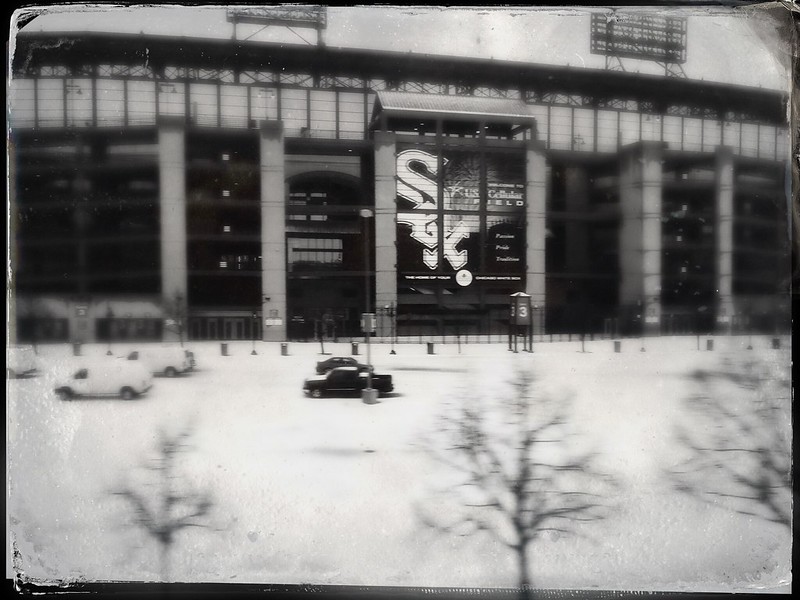

Whether you call it Cellular Field, Guaranteed Rate Field, or Comiskey Park, the home of the White Sox is sometimes a surprise highlight for Amtrak passengers. If you look at the satellite view of the ballpark, though, you won’t believe the number of train tracks to its west. On the starboard side of the train, eastbound Amtrak passengers can enjoy the view of Universal Granite and Marble.

(I don’t like other names)

Apparently a scrapyard in Michigan City, Indiana, has mastered Monty Python’s art of “putting things on top of other things.”

41 42′ 25.80″ N, 86 54′ 34.80″ W

I couldn’t figure out the purpose of this attractive building with cupola, but was surprised to realize later it’s in Michigan City, Indiana, not far from the Old Lighthouse Museum. The Hoosier Slide mentioned above was across from the lighthouse on Trail Creek where it empties into Lake Michigan, near this building. That would have been something to see from an Amtrak train. Now the Hoosier slide site is covered by a NIPSCO coal-fired plant. Progress. Rest in peace, Hoosier Slide. May we not forgot what we have lost and never known.

41 43′ 18.18″ N, 86 54′ 15.75″ W

This wavy fence in Michigan City, Indiana, baffled me. I’ve seen them elsewhere, I think, but I don’t know the purpose other than aesthetic.

41 47′ 48.26″ N, 86 44′ 41.29″ W

There may be millions of nondescript, decaying buildings across the U.S., but I haven’t spotted many more nondescript than this one.

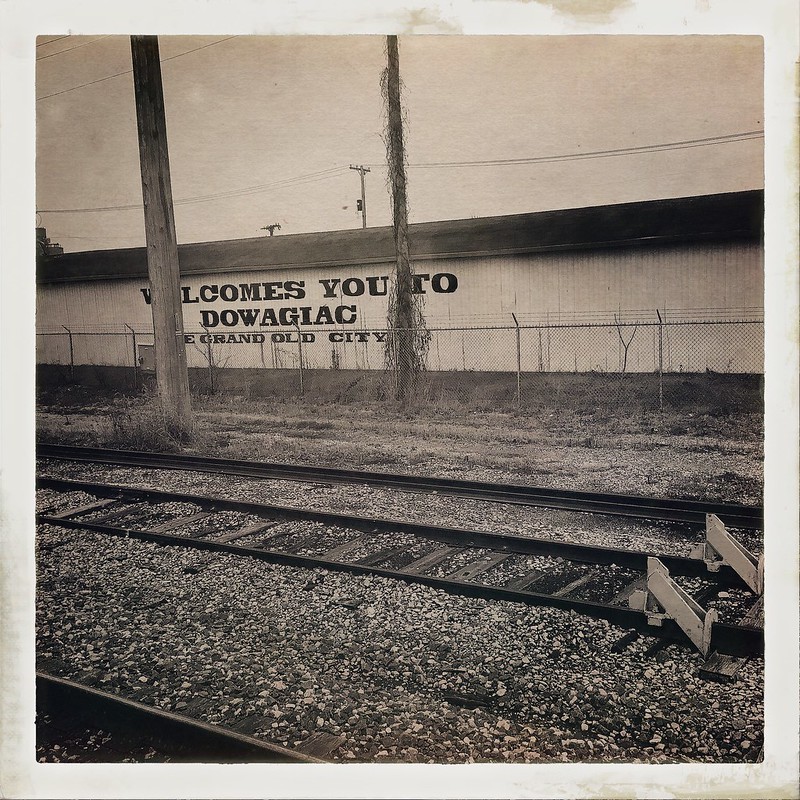

The appearance of this building belies its message that Dowagiac, Michigan, is the “Grand Old City.”

41 58′ 50.28″ N, 86 6′ 34.05″ W

I noticed this long red building on the edge of a small stand of trees in Parma, Michigan, east of Battle Creek. In the satellite view, a dirt road from another building, likely a house, is the only access to it. I’m intrigued by the tall chimney.

42 15′ 36.00″ N, 84 36′ 4.80″ W

With no immediate neighbors, this house, likely part of a tree farm, looks lonelier than it is.

42 15′ 55.80″ N, 84 35′ 5.40″ W

Farm buildings dot the back roads, and rails, of middle America.

42 15′ 51.60″ N, 84 34′ 47.40″ W

Some houses in Pennsylvania towns like Johnstown are spaced closely together, with nearly touching side walls or an alley almost too narrow to squeeze through.

40 20′ 34.94″ N, 78 56′ 14.80″ W

These houses on a hill are farther apart. I wonder if they would have been high enough to escape the Great Flood of 1889—or any since. The area’s geography makes it prone to flooding even without breaking dams.

Johnstown, too, has nondescript commercial buildings.

Stations

Some Amtrak stations, like the modern monstrosity in Ann Arbor, are cold and utilitarian. Next door, Ann Arbor’s former station has been converted into an upscale restaurant, Gandy Dancer.

Old school stations remain in use in Michigan and Indiana.

42 14′ 52.20″ N, 84 23′ 58.80″ W

42 14′ 52.20″ N, 84 23′ 58.80″ W

Often there’s not much to see in the dark, but I spotted the same rotting cars from the EB Capitol Limited. Nearby I found a National New York Central Railroad Museum. If they’re intended to be exhibits, they may use a little work.

Elkhart, Indiana

Coming and Going

The morning Dan Ryan Expressway from Amtrak.

This is what you, and New Buffalo, Michigan, look like to an Amtrak passenger.

As children, we liked to watch for the caboose at the end of long freight trains. When the news pronounced the demise of the caboose, I was distraught. When I can, I watch the scenery recede from the last car of the Pennsylvanian, unimpeded by a caboose, remembering the miles of track and the cities, towns, stations, farms, taverns, fields, rivers, creeks, houses, plants, and stores behind me — and ahead of me on the return.

Finally, all journeys must have an end. Mine passes over the Calumet River through Chicago’s steel history.

Ghastly photos

Halloween is coming up, and I thought of a few photos I have that are a little . . . off.

Bailly Homestead at Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore doesn’t look welcoming even in broad daylight when seen through the Hipstamatic Bucktown filter.

This is the Pepperland in Hyde Park, a Victorian-style apartment building popular with University of Chicago students. It could be haunted.

Old Hickory in Coudersport, Pennsylvania, has seen better days. It’s said that Eliot Ness was a guest. It could be haunted if it weren’t for the pigeons that have taken over.

Near the Bailly Homestead, Chellberg Farm is more forbidding when the trees aren’t in leaf.

This cemetery in Force, Pennsylvania, and the weird lighting and shadows caught my eye.

I don’t know which is worse — the tree or its reflection.

Excellent paint job at Fullersburg Woods.

Long-abandoned hotel in Gary, Indiana.

If I didn’t know better, I’d think there was a ghost at the Bailly Cemetery at Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore. It’s only me. Paler than usual.

Spectacular Miller Woods

15 July 2018

On the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore events calendar, the National Park Service refers to “spectacular Miller Woods.” I’ve never gone on the ranger-led hike—it’s probably more than I can handle—but J and I decided to try out “World Listening Day Program and Sound Hike” with the Chicago-based Midwest Society for Acoustic Ecology.

First we had to get there, which isn’t easy with temptations on the way. At a corner close to our destination, we spotted the Miller Beach Farmer’s Market, where we spent time and money. I love open air markets, even when they’re in a small, dusty parking area.

I had no idea where Miller Woods was, but it’s down the street from Miller Bakery Cafe, where we’d gone for dinner a couple of times. It’s a hidden gem. After parking, you walk over a shaded enclosed pedestrian bridge to the Paul H. Douglas1 Nature Center, which has interesting exhibits and helpful young rangers, and, on this day, leftover cookies. I learned a different way to tell frogs and toads apart (frogs have a prominent tympanum).

After checking out the animals (and the cookies), we met Monica from the Midwest Society for Acoustic Ecology at the back exit. Behind us was the Miller Beach neighborhood of Gary, Indiana, with stores, restaurants, gas stations, etc. In front of us was a dunes woodland with ponds and two beaver dams, leading to a beach (we didn’t go that far). I had one of my fleeting moments of feeling like I was stepping out of reality into a magical place, separated by time and space.

We arrived an hour or so before the hike was to end, but Monica and her photographer husband told us only one person had shown up earlier. The idea behind this walk was to be as quiet as possible—a struggle for an extreme extrovert like J—and to listen to the sounds around you, how they change as you move, and so forth. I decided I’d better warn her that both he and I have faulty hearing, partly so she’d know our ears might not pick up every nuance hers did, and partly so she’d know that we might not hear her if she spoke quietly.

Off we went, with her husband well in front of us. Miller Woods is fairly quiet for being in an urban area, and I soon became aware of how much noise I can make walking on stony ground if I barge forward—and, interestingly, that my left leg drags more often than my right. A train, I think Amtrak, rumbled through to our left, which was my first indication of train tracks at Miller Woods. One or two birds called repetitively, although at times and in places the birds were quiet.

At the point where we looped back, we could hear a low rumbling (“groaning,” as Monica described it) to our left. She told us there’s a plant of some kind in that direction.

At another place further on, I imagined I heard a skittering on the ground and spotted this insect. I say “imagined” because there’s no way my damaged hearing could pick up an insect’s exoskeleton or wings on stone.

When we were at a low point, she noted how muted and absorbed sound seemed to be (like sound in snow). At a high point after a steep climb up sand, sounds carried—tree leaves rustling, birds calling, sounds in the distance. I told her about aspens, which to my surprise she didn’t know about.

All this time I was tempted to take photos, but kept them to a minimum—even the sounds of the shutter in the relative quiet seemed too disruptive.

Just as we were reaching the end near the nature center, J and I heard a deep strum from the nearby pond vegetation that our guide hadn’t—most likely an American bullfrog. He strummed a few times before we left.

Inside we talked with Monica, her husband, and an older man with a microphone about their organization, iPhone add-on, aspens, and other topics. We learned Monica and spouse live on the north side of Chicago and had taken the train and a shuttle to Miller Woods; they would have to wait until after 6 p.m. for the next train on a Sunday. Dedication! I felt bad they’d had an audience of only three for all that effort.

I found the young rangers eager to answer questions and chat. When I wandered back to the desk from the restroom, I found the two young men pulling the fronts of their shirts down and looking/pointing. I may have looked at them strangely. “We’re comparing our shirt tans,” one explained.

When he’d heard dinner was next on our agenda, the older man with the microphone suggested we try Captain’s House. The proved to be a charming restaurant in a house with a nautical theme and a seafood focus (and alternatives for the seafood averse like me). Next time we’ll have to choose a bigger table.

Is Miller Woods “spectacular”? I can’t say. It’s not the Grand Canyon, Arches, Yosemite, or Yellowstone. We didn’t see all of Miller Woods—the trail goes out to Lake Michigan. All I can say is it was spectacular to me. Now, if I could spot a Karner blue butterfly there . . .

1 Paul Douglas was the Illinois senator who had worked to establish Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore.

Sun rays and clouds

Watch out for wildlife, hazards, and polite requests (signs of the times)

I don’t see signs about wildlife very often, although this one at Windigo, Isle Royale National Park, warns unsuspecting visitors about the island’s less famous, thieving canine. What do the red foxes of Isle Royale do with the car keys and hiking boots they purloin?

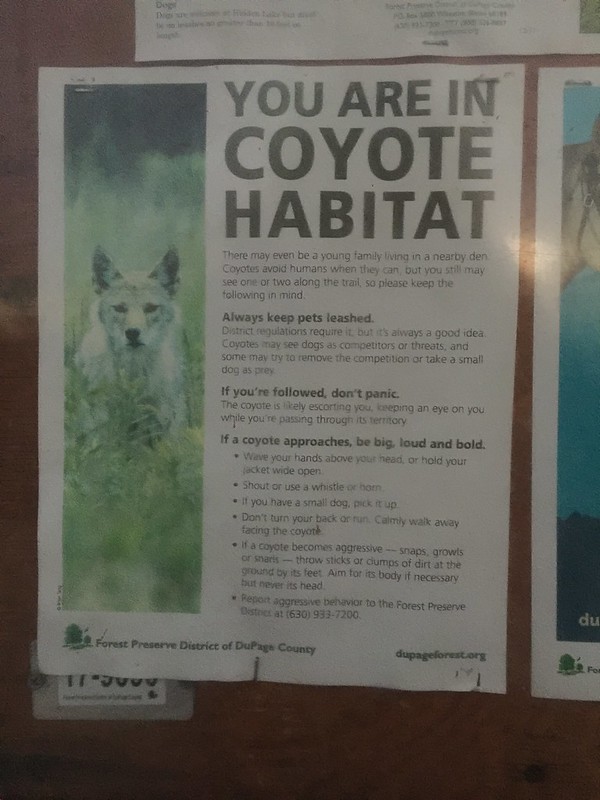

This sign, at Hidden Lake Forest Preserve near Morton Arboretum, exhorts you not to panic if Wild Fido follows you. He’s simply giving you an escort through his domain. If this task makes him snappish, simply throw clumps of dirt at the ground by his feet. I’m having visions of Monty Python and “Confuse-A-Cat.”

Other signs warn you about smaller wildlife, especially the kind that hops aboard. This one, at Michigan’s Grand Mère State Park, tells what to wear to help stave off the dreaded tick. By the time you’re at the park, however, you may not have clothing alternatives handy. The tick shown is terrifyingly big, but the ticks that can share Lyme disease with you may be little larger than a pinhead.

Pro tip: At Shawnee National Forest, which is tick heaven, I thought wearing a hat would keep them off my head at least. Not so. After a delightful morning at Pomona Natural Bridge, I felt movement in my hair and found a couple strutting under my hat on top of my scalp. This is one of those times when baldness would be an advantage.

Located at a town park near Grand Mère, this sign is not so much a warning as a caution. If you aren’t careful and you spread the emerald ash borer, this will happen to your ash trees. I can attest to the lethal behavior of the well-named emerald ash borer—both tall, mature trees in front of The Flamingo, plus the mature tree that shaded my bedroom at 55th and Dorchester, succumbed to these little green scourges.

At Hidden Lake Forest Preserve, we’re told it’s too late to keep out another horror, the dreaded zebra mussel. You can be a hero, however, by cleaning your boat and equipment properly so you don’t transplant them to a body of water where they haven’t taken hold. The use of “infest” is a great touch. It reinforces the nearby “No swimming” sign nicely. Swimming in infested waters just doesn’t appeal to me, even if I could swim.

If you’re about my age, you recall that “only you can prevent forest fires (that aren’t caused by lightning strikes, volcanoes, and other natural hazards). Many parks post the current risk of wildfire danger based on conditions like drought and wind. At Lyman Run State Park in the Pennsylvania Wilds, Smokey Bear can’t seem to make up his mind.

This version of Smokey opted for words instead of visuals, which makes his message less ambiguous (no broken pointer). No doubt that snow on the ground helps to keep risk low.

Taking shape on Stony Island Avenue in the remnant heart of Chicago’s steel industry, Big Marsh Park features a bike park (built on slag too expensive to remove), natural areas, and occasional bald eagle sightings. An enticing hill nearby forms a lovely backdrop for a walk at Big Marsh, which is still in its infancy. When you get closer, however, and read the signs, you learn it’s a steaming, seething landfill that’s being “remediated.” There’s no happily running up and down this slope. How I miss the Industrial Revolution.

It’s not every day you’re warned about lurking unexploded bombs, but for me this was no ordinary day. It was my first visit to Old Fort Niagara in nearly 40 years, which coincided with Memorial Day weekend. Most of the time, the fort is manned by soldiers in 1700s military fashions, but in honor of the holiday other conflicts were represented. I kept my distance from the bomb. Just in case.

This is one of the odder warning signs I’ve seen. I left the chef alone—after all, he works with sharp objects.

Slow down. Chicago is under a budget crunch, but do they send out a lone fireman like this? A lone fireman without a steering wheel? Or arms?

Here’s a warning sign you can ignore. It’s outside Riley’s Railhouse, a train car bed and breakfast in Chesterton, Indiana, that’s a treasure trove of signs.

From the exterior of the car I slept in:

At Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore’s West Beach, it looks like the National Park Service is testing which sign or message is most effective at keeping visitors off the dunes. This one shows bare tootsies with the universal “No” slash, helpfully pointing out the dunes are ours.

A less friendly, sterner, more wordy one admonishes you to “KEEP OFF THE DUNES” and appeals to your desire to “Please help protect and preserve our fragile dune systems!”

At the beach, this slash through a barely visible hiker shuns wordiness (or words) for directness and simplicity without justification or explanation.

It’s sandwiched between even more minimalistic signs with a slash, planted where the dunes start ascending. Don’t. Just don’t.

Years ago when a landfill near my cousin’s house became a Superfund site (just what you want in your backyard), it was surrounded by an electrified fence complete with warning signs. Noticing there were no insulators, I dared to touch it. In this case, however, I’m certain the area behind the fence is dangerous, and this is as far as I got.

Normal weathering or resentment over the weapons message?

Waterfall Glen, a DuPage County Forest Preserve, forms a ring around Argonne National Laboratory, “born out of the University of Chicago’s work on the Manhattan Project in the 1940s.” Naturally, the immediate area around the lab is secured. While I was baffled by this sign about “lock installation” and “any unauthorized lock,” it was the 10 or so locks on the chain that got my attention. Why do people need to add locks to that chain? Why do they need authorization? From whom do they get authorization? Why are unauthorized locks removed? What does it all mean?

Remember when lead was thought to be safe? I don’t, either. This sign is on an old pump at the remnants of an old general store in the western part of Shawnee National Forest.

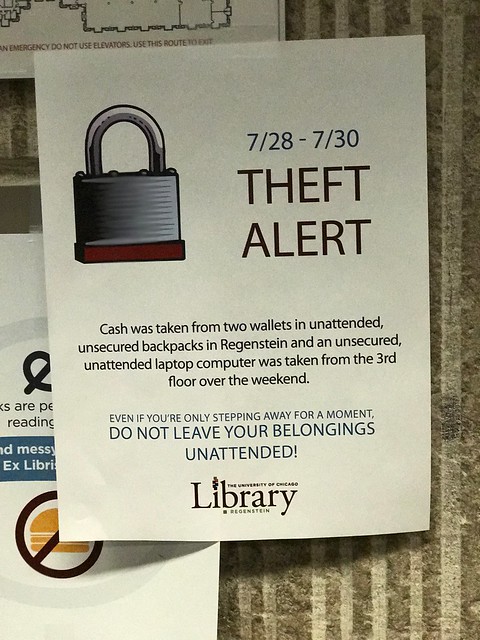

Warning: If you leave expensive stuff lying around, even at an exclusive university, it will walk off. You can bank on it.

RATS? There are RATS in Hyde Park?