June 19, 2022

J had thought to go to Sagawau Canyon or Chicago Botanic Garden, but the roads were too red and the delays too great for my tolerance (33+ minutes!). He suggested the National Park Service property closest to me — Pullman National Monument, about 20 to 25 minutes away via Stony Island, potholes and all.

A ranger who seemed happy to see visitors greeted us and gave us brochures and a neighborhood map. When I saw Cottage Grove and a Metra stop on the map, I realized I pass within a few blocks of the visitor center when I take Metra to Homewood or University Park. The Kensington station is at 115th Street and Cottage Grove. Pullman is near Lake Calumet, Big Marsh Park, Indian Ridge, and Dead Stick Pond, and not far from Hegewisch Marsh and Beaubien Woods. It’s a strange area, abandoned in part by industry, bisected by I-94 and its ceaseless noise, and only partially reclaimed by wetlands.

The visitor center is well laid out. Our ranger friend told us the second and third floors are being developed, and the building across the way, roofed with plastic sheeting, is being restored by the state of Illinois.

As someone who’s not from Chicago and who’s never fully embraced living here, I didn’t know much about Pullman or the economic and labor situation. From the 1890s, I know more about serial killer H. H. Holmes than anything else. Now I know a bit more.

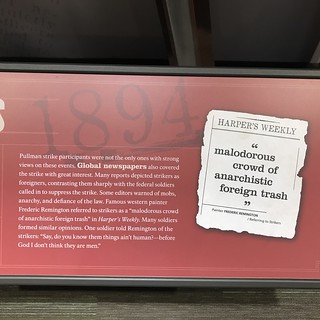

A timeline on the wall shows the history of Pullman, from its association with luxury and its conversion to wartime production (twice) to its final delivery in 1981 to Amtrak. Mixed in are episodes of economic, social, and labor unrest, with federal troops called in, firing on and killing striking laborers.

Other exhibits include a gander at what a Pullman car looked like on the inside, with reproduced seats and ceiling. A video shows a porter at work putting up a bed and a couple commenting on the car’s luxury. Displays cover the Pullman neighborhood and the restricted life lower-level employees led — what would it be like to sleep, eat, and be entertained within steps of work, with little means to go anywhere else day to day?

Race is part of the rail labor story. While many Pullman porters (most? all?), like one of Michelle Obama’s ancestors, were African American, they were not allowed to join the new rail labor unions. In their conflicts with the upper business classes, the unions turned down help from people with whom they had common cause, apparently without seeing the irony. To be fair, it’s noted that labor leader Eugene Debs did not agree with this choice to exclude African Americans.

One great thing about the visitor center exhibits: They’re tactile and include Braille. Instead of, say, a flat drawing of a Pullman car, the graphic is grooved or carved so you can feel the shape and details. Sometimes Iv’e wondered if Braille is an endangered language but it seems not.

There’s also a spot where people, mostly children, can write their reactions. I wish I’d taken photos. One wrote that while capitalism has some benefits, it also creates problems, which are listed. That kid is smarter than the average bear, as we used to say.

The exhibits draw such observations out by asking questions about life for laborers, many immigrants, in the shadow of privileged and wealthy owners and leaders, and about the violence of the government response when rail service linking Midwest and West was severed. I’d like to think it wouldn’t happen again, but these are “interesting times,” with income disparity and other inequities driving unrest, overt and covert. While Pullman may seem to be in the distant past, the issues resonate today.

There is, of course, a very good gift shop, where we learned the author of one of the books for sale (which I was buying) was speaking nearby. His talk would have been half over by then, so I passed.

Afterward we drove around a bit to see some of the neighborhood’s highlights and housing. I especially liked the livery stable.

Next to the Lake Hotel, we found Gateway Garden. We’d seen a sign on a house about local honey; J discovered the property contained many, many beehives. They must have more than Gateway Garden to meet their needs. Unlike J, I didn’t see the apiary or meet the owners, but I wonder if they get complaints. I hope not.

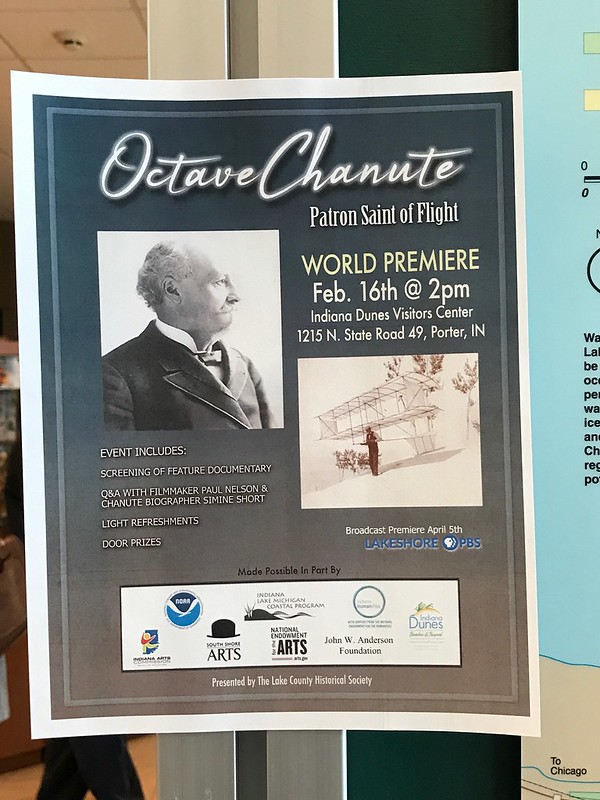

See this article from May 2022: ‘Good memories’: Brothers revisit last Pullman passenger rail car they helped build