March 31, 2019

I’d gotten an email about volunteer opportunities at Indian Ridge Marsh, which I had not heard of before. Referring to Google Maps, I saw it’s near Big Marsh Park and Hegewisch Marsh, so J. and I decided to check it out.

It turns out it’s a couple of blocks east of the landfill south of Big Marsh. When we arrived, I realized it’s exactly the fenced area we’d passed at night a few years ago that looked dark, grassy, and empty of industry and that had intrigued me. I’d wished then that it was open to the public and to visit it during daylight hours. And here I was, even if unwittingly.

Indian Ridge Marsh lives up to the “marsh” part of its name. Parts of the trails we saw were under water, and the first one we took (south) was so waterlogged I sank into it up to my ankle and almost got stuck (reminding me of a similar experience on the way to Lusk Canyon/Indian Kitchen in Shawnee National Forest).

The other trail looked wetter, but wasn’t as soft. It led to water divided by a ridge, with another ridge to the west. On Google Maps, the water looks like almost like somewhat regularly shaped holding ponds. I wonder if this is their natural configuration or their steel industry one.

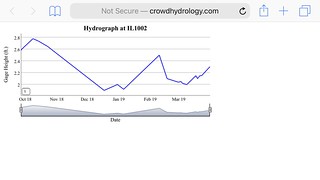

Rulers in the water to the north and west of the E–W ridge, where the trail runs, show water depth. You’re invited to participate in “crowd hydrology” by texting the depth to a number, after which you get a reply text, and the depth appears on a website. Our March 31 measurement at the western ruler was 2.4 feet, which binoculars helped my aging eyes to see.

Train tracks run on top of the N–S ridge, and we watched as NB and SB Norfolk Southern freights met and passed, with the SB stopping for a while.

Across the street from the parking lot and to the south a cut through a ridge reveals the Calumet River and an active industrial area. Past that a steel bridge on Torrence crosses the river. Next to the south end of the bridge a deer crossing seems out of place, given the immediate surroundings.

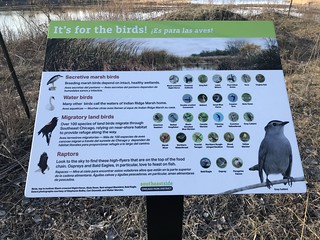

We parked in a little area north of the bridge and walked across a wooden bridge to more wetland areas, which may have been Heron Pond Park. Although we couldn’t see it from our vantage point, I’d seen a swan from the street. If I had wings, I’m not sure I’d want to hang around an industrialized wasteland. I can only imagine how important Lake Calumet and these neighboring marshes were and are to migratory and resident birds.

When we headed west toward Big Marsh and came to the landfill, we found perhaps a dozen deer munching away on its grassy slopes, oblivious to the warning signs. Further north at Big Marsh, a great blue heron was poised over a channel, flapping off majestically to the opposite side of the water at the sound of the engine. Beyond it more deer were having supper. The sign south of the bridge makes me wonder how far these little herds wander out of the marshes into those nearby industrial areas.

Finally we ended up at ye neighborhood tavern, Small World Inn Bar & Grill, where we were the only outsiders, sitting at a table instead of at the bar. If you’re in the mood for cevapcici (Serbian skinless small grilled sausages of beef, lamb and pork), this is the place for you.

More about Indian Ridge Marsh here (PDF).