September 1

I still needed most of the day to recuperate, but I recovered in time to request a trip to Ritchey’s Dairy for teaberry ice cream. Only (or mainly) in Pennsylvania. Delish.

My journeys on the Capitol Limited and Pennsylvanian were uneventful. The Capitol Limited arrived in Pittsburgh 40 to 50 minutes before the Pennsylvanian left, so it was a little close — but no Greyhound this time. I got my eastbound trip around Horseshoe Curve, although by looking to the inside I missed the derailed center beams on the outside – on both sides. (There were two derailments at the Curve this summer.)

I arrived in plenty of time to go on an outing to load up on spring water at Elk Run near Tyrone. Many, many bald-faced hornets were feasting on the plants by the stream.

We also stopped at a farm in Sinking Valley to pick up what turned out to be the last corn on the cob of the season and later shuck it for an evening “mountain pie/hotdog cookout and corn boil.” I wish I’d taken a photo of my ham and cheese mountain pie. Delish.

December 27, 2017: After seeking elk in the outlying areas of Benezette, we found a little herd at the campgrounds in town, which they favor. I handed my phone off to my cousin, who was in a better position to capture them. Benezette is part of the area that’s been rebranded “Pennsylvania Wilds” to attract adventurous tourists of the have kayak, will travel variety.

Today is the 100th anniversary of my mother’s birth. I discovered this delightful clipping about a hike to a farm and a picnic with storytelling under a big tree she helped to organize. It could be straight out of Anne of Green Gables.

I love finding these blurbs. This and others are giving me new insight into my parents’ early lives pre-me.

As a child, I didn’t think about water until I started visiting a friend whose family drank well water that smelled and tasted of sulfur. The odor permeated their house. “You get used to it,” she said. Accustomed to the tasteless taste of “city water,” invariably I felt thirsty the moment I arrived. I never got used to it.

Forty-five years ago the typical person didn’t carry a water bottle or buy bottled water. We drank whatever came out of the tap. Unswayed by Dr. Strangelove or decades of bottled water marketing, I still do, and that’s what I fill my insulated water bottles with when traveling.

On our annual pilgrimage to Pennsylvania in the 1960s and early 1970s, we used to stop at a couple of roadside springs and fill a jug or two with spring water. We didn’t need to. Our “city water” in New York was fine with us — well, as fine as any water in our polluted world can be. There didn’t seem to be any objection to our hosts’ water, either. By the time I was sentient, we were no longer staying with anyone who lacked indoor plumbing. My guess is my parents liked the idea of getting water from a roadside spring and preferred it as a rare treat. I did too. Water straight from a spring — as nature intended. (We didn’t boil it, either.)

Later we stopped at the usual places and found signs indicating the water was too contaminated to drink — the effects of coal mining. My heart broke a bit at the loss of a tradition and the sense the earth itself was dying one roadside spring at a time. After all, I was being raised in the era of the fiery Cuyahoga River, algae-choked Lake Erie, and the horrors of Love Canal.

I wish I could remember where those springs were and find out if anything has changed.

According to findaspring.com, which seems to be defunct, Pennsylvania leads the U.S. in the number of listed springs with 84. New York is second with 59, while Illinois lags behind with only 17 shown.

When I was visiting my cousin for Christmas 2018, I found out they’ve taken to collecting and drinking spring water. My cousin hinted, however, that the spring is far from picturesque. In my mind’s eye, I saw an ugly, chipped-up plastic pipe protruding from an ugly, denuded hillside in town. Something like that.

The spring is south of Tyrone, so we used a visit to Village Pantry as an excuse to get some water. It’s on a lightly traveled road paralleled by a stream, Elk Run, that seems to cross back and forth under it in several places.

My cousin and his wife quickly set up an efficient two-person jug-passing and -filling operation while I meandered back and forth across the road, drinking in (so to speak) the sights and sounds of the spring and Elk Run on its journey.

When a house buyer sees a stream, he pictures flooding, damage, and dollars. I picture myself at a church picnic at Chestnut Ridge, a lifetime ago, walking on 18-Mile Creek, listening to its gushing and trickling, soaking in the sight of countless tiny drops, waterfalls, and eddies, and hoping to spot tadpoles, frogs, minnows, and fish in the clear water reflecting a perfect summer sun filtered on the edges by healthy trees. I had no way of knowing how ephemeral that experience would be.

Memories.

I don’t know how clean or safe the water from this spring is. As I said, it’s south of Tyrone, whose paper mills wafted their distinctive odor through my aunt’s screen door seven or eight miles away in Bellwood. I’ve seen a discussion about agricultural runoff in the area as well, although many think it’s insignificant.

Elk Run appears to be a tributary of the Little Juniata River. I once told my dad I’d seen a leopard frog in the Little Juniata as it runs past Logan Valley Cemetery in Bellwood. He made a wry comment about it, perhaps “How many legs did it have?” Now he and my mother are buried in Logan Valley. Cemetery, within earshot of the Little Juniata. Water, however clean it is or is not, connects us — all of us. We shouldn’t forget that.

Curious about the current state of the Little Juniata, given I’d been handed two bottles of spring water, I found out it’s not as bad as I thought.

Well, the Little Juniata River is not well-known nationally, primarily because it’s only been a trout stream since around 1975. The reason being that prior to that it was literally an open sewer.

Bill Anderson, president of the Little Juniata River Association

After decades of pollution and a “mysterious pollution event in 1997,” we have brown trout fishers to thank for cleaning up the Little Juniata and shoring up its eroding banks.

We want to make sure this resource stays open for our children and grandchildren.

Bill Anderson

This would have made Dad happy. And he didn’t fish.

This morning I, “Dianne Schirg,” made this marvelous discovery from a simpler time when a family visit to Bellwood, Pennsylvania, was noteworthy.

On my last full day in Pennsylvania, the 28th, we went to the Flight 93 National Memorial despite the government shutdown. Our route took us down Lincoln Highway, which crosses the United States. It passes through Illinois in the far south suburbs of Chicago. Lincoln Highway reminds me that all of us are connected in some way.

We arrived first at the Tower of Voices, which with the surrounding landscaping are a work in progress. When completed, there will be a chime for each crew member and passenger on Flight 93 — 40 in all. At this time, there were eight if I recall correctly.

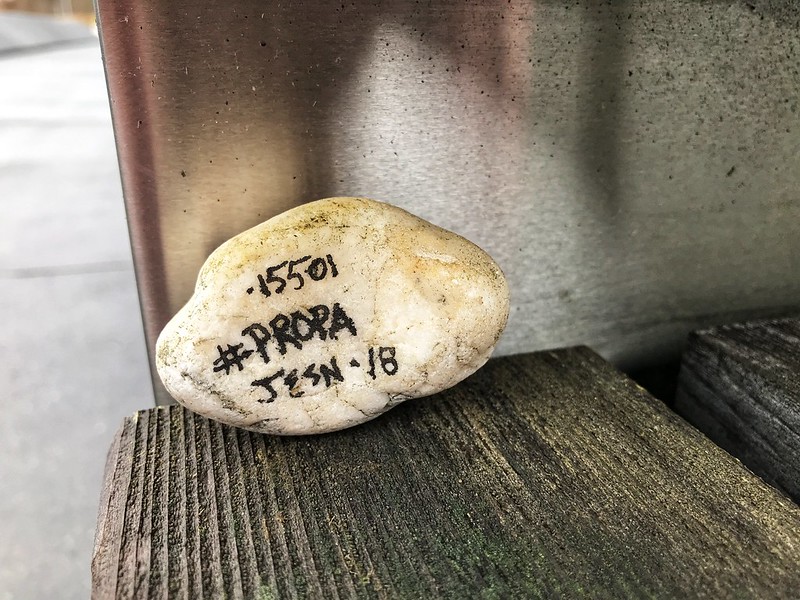

On a bench near the Tower of Voices, we found a “Painted Rock of Pennsylvania.” This is a thing I must look into. I loved this one.

The memorial site is a few miles off, with some farm buildings and wind turbines the main signs of habitation. Before 9/11, the residents of Shanksville and environs could not have imagined visitors from around the world making pilgrimage to their community a half hour south of Johnstown.

The site, which is large, was once a surface mine, stripped of most trees and since replanted. Due to the shutdown, the date, and possibly the gloomy but unseasonably warm weather, there were some but not many people about. We took our time walking to the wall where the names are inscribed, passing the large sandstone boulder that marks the area where the plane came to rest — violently. Someone had left flowers by a few of the names in the wall.

We found another Painted Rock of Pennsylvania on a bench along the way.

I found out via the Facebook hashtag #PROPA that the artist hadn’t expected them to be found until spring. I left both for others to find.

On the way back to the parking lot, we looked at some graphics, then drove to the visitor center. The high walls, marked with the hemlock lines that are the prevailing theme even in the sidewalks, show the path the plane took. In this case, the design’s simplicity adds to the solemnity of the place and inspires the imagination, especially when you remember this horrific event took place on a perfect sunny day in the waning summertime.

The visitor center was closed, of course, but we could see quite a bit through the glass. I wouldn’t have wanted to eavesdrop on those final conversations even if I could have.

On Lincoln Highway, I’d noticed signs for two covered bridges that didn’t seem to be far off — two or three miles, more or less. The first, Glessner Covered Bridge, was down a well-maintained dirt road — not too rutted. The covered bridge is lovely, with a barn on one side and railroad tracks that parallel the stream on the other. The stream is known as either Stony Creek or Stonycreek River. The latter seems redundant. It’s either a river or a creek, but neither is a clearly defined term.

The generous landowner at Glessner covered bridge has posted signs — not the usual “Private,” “Posted,” “Keep Off,” etc,., but signs inviting you to enjoy a little fishing if you’re so minded. I call that right neighborly. It would be a lovely spot to fish in the warmer months.

To get to Trostletown Covered Bridge, we passed Stoystown Auto Wreckers, quite possibly the largest junkyard I’ve ever seen — acres and more acres of junk cars at the bottom of rolling hills. As I recall, the Google Maps capture shows only a portion of the junkyard. Today — unsightly metal carcasses. Yesterday — bucolic covered bridges.

Google Earth image shows the size better.

I’ve read in several places that Trostletown Covered Bridge passes over Stonycreek, or Stony Creek River(?). I use a question mark because Google Maps shows Stony Creek River west of the bridge. I wonder if what we saw is a little offshoot — it doesn’t even appear on Google Maps in blue.

The water, wherever it comes from, doesn’t quite flow freely under Trostletown. It was low and in many places choked with plants and earth. Unlike Glessner Covered Bridge, which is open to cars, Trostletown doesn’t seem to lead anywhere, but ends in a seedy and weedy area. I’d want to plant a butterfly garden with benches there.

I teased my cousin’s wife about driving across the Trostletown Covered Bridge, but she’d already noted it goes nowhere. I drew their attention to another deterrent — a Conestoga wagon blocking the way.

Google Earth shows Trostletown Covered Bridge to your right from the bend in the road.

Trostletown Covered Bridge and the Conestoga wagon are not the only remnants of history here. Kitty corner from the covered bridge the Stoystown American Legion post features a tank and a helicopter positioned to nosedive into the ground. I read elsewhere it’s a Vietnam-era Huey.

On the way to and back, mist smothered and covered what lay in the hollows, often following the meanderings, we thought, of streams and rivers. You can’t quite capture it from a moving vehicle.

Although the day had been gloomy, there was one brief hint of life and color as the sun appeared while making its daily disappearance.

Days like this make leaving harder than it already is.

Horseshoe Curve, 10 minutes outside Altoona, Pennsylvania, is a world-famous National Historic Landmark — so the signs say. It’s not on the beaten track.

When my family used to visit their families in the Altoona/Bellwood area, sometimes we’d make a side trip to Horseshoe Curve. I still have a souvenir calendar from way back when. Note that it was not “World Famous Horseshoe Curve,” but plain old Horseshoe Curve.

I don’t think we paid admission. My dad wouldn’t have paid, or would have paid only a nominal fee, for something as nonessential as a trip to Horseshoe Curve. I remember only that at some point, I’m not sure when, he commented how “overgrown” it’d become, which made it hard to see much.

In September 1988, after I’d been absent for awhile from Pennsylvania, my aunt took me to see it again. The only way to get up then was steps, difficult for her because she’d lost a kneecap to a car accident. You can see why my dad said you couldn’t see much for the trees and brush.

In the early 1990s, a visitor center/museum was built, along with a funicular to get up to the top for those who don’t want to or can’t handle the steps. Now there’s an admission charge to see the Curve, which you can go up to only during the posted season and hours. It’s pricey for a family, and there’s no break for Blair County residents.

I’ve seen Horseshoe Curve as a passenger on Amtrak 42 (eastbound) and 43 (westbound), the Pennsylvanian. On this visit I didn’t, however. A freight train accident with a vehicle ahead of the Capitol Limited had made me miss the connection with the eastbound Pennsylvanian, so I’d had to take Greyhound from Pittsburgh to Altoona. On the way back, the Curve is dark when the Pennsylvanian passes at around 5:30 p.m.

The public can’t access Horseshoe Curve during the colder months. When we made a quick stop the day after Christmas, we just looked up. I’ll have to make a trip sometime in late spring, summer, or early fall for a real visit.

Countless trains have passed downhill toward Altoona and points east since Horseshoe Curve was finished in 1854, engineered by J. Edgar Thompson.

Kittanning Run passes under Horseshoe Curve from the north. It’s too bad there’s not a more bucolic fence to protect the public from falling in.

Of course you want to hear that water flowing. The odd thing is . . . I don’t recall anything but the reservoir. You’d think I’d remember hearing or seeing rushing water, but I don’t.

Pushmi-pullyu pairs of black-and-white Norfolk Southern helper engines go back and forth on Horseshoe Curve all day. They’re needed going uphill to pull/push and going downhill to help control speed/brake. You don’t want a long, heavy, fully loaded train speeding downhill around a curve. These two are headed back up the mountain.

It’s Pennsylvania, so you will see coal trains. You can imagine how much they weigh. This one is going downhill east toward Altoona in Logan Valley.

Poor scans of photos taken in 1988 remind me of my dad’s move to Pennsylvania. We had visited family there at least once a year during most of my childhood. As my dad got older, my parents and their family members started to have health issues, people died, and I went to college, we stopped going. By the time I returned to the Altoona area, it seemed strange, yet familiar. What felt oddest was getting there mostly by Amtrak vs. wending our way through southern New York and Pennsylvania on Rte. 219. I felt like a stranger in a strange land, with my mother and many of her family already gone.

Since it was one of my first visits in a long time, my dad’s sister took us to several area attractions. I’d never seen Baker Mansion. The kitchen trough for fresh fish fascinated me. I also recall servants’ quarters at the top of the house. I imagined helpless cooks and maids trapped in the attic while fire raged below, the small windows useless for escape.

We also went to an overlook, but I paid little attention to the name (if it was mentioned) or the location. We didn’t have Google Maps in our pockets for reference 30 years ago. I remember only the loveliness of the view — and that when I went to look over, I slid on shale or gravel and tumbled partway down the hill, my fall slowed, then stopped by a tangle of brush. I laughed.

During my Christmas visit in December 2018, I mentioned the photo to my cousin and his wife, who agreed I must be talking about “Wopsy” (Wopsononock Mountain). It’s directly across from Pinecroft.

From the top of Wopsy, we could see the housing development that replaced the woods on their hill, the old landfill, and perhaps a corner of their house or garage. I realized that the towers I see from their road are where we were standing on Wopsy.

Where once there were wooden fence posts there’s a long, high guardrail covered with grafitti; my cousin feels the area’s not that safe. Devil’s Elbow, which we may or may not have passed, is supposedly haunted by the “White Lady of Wopsononock.” If you don’t believe in the White Lady, you can check out Mindhunter on Netflix about the murder of Betty Jean Shade, whose body was found in an informal trash dump on Wopsy.

What made the death of Betty Jean Shade so different was the violence to her body, and in an effort to determine who killed her, investigators, through the aid of former FBI Agent Dale Frye, who served the Altoona area, turned to the fledgling FBI effort at its Quantico, Va., facility, which was attempting to perfect psychological profiling.

Phil Ray, Altoona Mirror

Betty Jean Shade was found in 1979, nine years before my visit. If I had known that, I don’t think I would have smiled so broadly. But the overlook is still beautiful.