Amtrak in Indiana via Lightt, part 2

Motion parallax is obvious here once you get past the trees and keep your eye on the power towers, which hardly seem to move, yet disappear.

Motion parallax is obvious here once you get past the trees and keep your eye on the power towers, which hardly seem to move, yet disappear.

Lightt was a short-lived video app I still miss. I didn’t have time to master it but I liked some of its effects. This video and a few others demonstrate motion parallax, which I had to look up after I noticed it.

I was on a weekend train to Chicago from Hamburg when I realized I didn’t have my Fitbit charger, which seemed important since the Fitbit was low on charge and might not last until Monday. This may have led me to notice I didn’t have anything at all for a trip, even extra clothes. But hadn’t I planned to return Monday?

I tried to figure out how to return, pack, go back toward Chicago — or maybe not.

Had I planned to return Monday or to stay to finish out a quarter? Why was I going? It’s an overnight trip, too long to be bouncing back and forth. [I did do that once, to Pennsylvania.]

As in yesterday’s dream (unpublished), my phone came up. I was about to take a photo when I noticed it was an earlier, smaller iPhone than mine. A nearby child cried that I had her phone. I gave it back wordlessly, expecting the mother to berate me, even have me arrested. She merely rolled her eyes and looked away, as though the child were in the wrong.

Every time I tried to take a photo, it was the wrong iPhone.

Horseshoe Curve, 10 minutes outside Altoona, Pennsylvania, is a world-famous National Historic Landmark — so the signs say. It’s not on the beaten track.

When my family used to visit their families in the Altoona/Bellwood area, sometimes we’d make a side trip to Horseshoe Curve. I still have a souvenir calendar from way back when. Note that it was not “World Famous Horseshoe Curve,” but plain old Horseshoe Curve.

I don’t think we paid admission. My dad wouldn’t have paid, or would have paid only a nominal fee, for something as nonessential as a trip to Horseshoe Curve. I remember only that at some point, I’m not sure when, he commented how “overgrown” it’d become, which made it hard to see much.

In September 1988, after I’d been absent for awhile from Pennsylvania, my aunt took me to see it again. The only way to get up then was steps, difficult for her because she’d lost a kneecap to a car accident. You can see why my dad said you couldn’t see much for the trees and brush.

In the early 1990s, a visitor center/museum was built, along with a funicular to get up to the top for those who don’t want to or can’t handle the steps. Now there’s an admission charge to see the Curve, which you can go up to only during the posted season and hours. It’s pricey for a family, and there’s no break for Blair County residents.

I’ve seen Horseshoe Curve as a passenger on Amtrak 42 (eastbound) and 43 (westbound), the Pennsylvanian. On this visit I didn’t, however. A freight train accident with a vehicle ahead of the Capitol Limited had made me miss the connection with the eastbound Pennsylvanian, so I’d had to take Greyhound from Pittsburgh to Altoona. On the way back, the Curve is dark when the Pennsylvanian passes at around 5:30 p.m.

The public can’t access Horseshoe Curve during the colder months. When we made a quick stop the day after Christmas, we just looked up. I’ll have to make a trip sometime in late spring, summer, or early fall for a real visit.

Countless trains have passed downhill toward Altoona and points east since Horseshoe Curve was finished in 1854, engineered by J. Edgar Thompson.

Kittanning Run passes under Horseshoe Curve from the north. It’s too bad there’s not a more bucolic fence to protect the public from falling in.

Of course you want to hear that water flowing. The odd thing is . . . I don’t recall anything but the reservoir. You’d think I’d remember hearing or seeing rushing water, but I don’t.

Pushmi-pullyu pairs of black-and-white Norfolk Southern helper engines go back and forth on Horseshoe Curve all day. They’re needed going uphill to pull/push and going downhill to help control speed/brake. You don’t want a long, heavy, fully loaded train speeding downhill around a curve. These two are headed back up the mountain.

It’s Pennsylvania, so you will see coal trains. You can imagine how much they weigh. This one is going downhill east toward Altoona in Logan Valley.

Once or twice a year I travel by Amtrak from Chicago’s Union Station — not cross country, just to Altoona, Pennsylvania, and Ann Arbor, Michigan. The Capitol Limited, Pennsylvanian, and Wolverine routes pass through cities, small towns, farmlands, and rusted sections of the Rust Belt. I ride the Wolverine during the day. The journey east on the Capitol Limited is all after dark, but on the return west we are in Indiana when morning dawns.

Amtrak passes through northwest Indiana, where in the late 1800s and early 1900s much of one of the nation’s most diverse ecosystems, the Indiana Dunes, was bulldozed over or carted off (see Hoosier Slide). Shifting Sands: On the Path to Sustainability shows the making of places such as Gary, Indiana, and the long-term costs of short-term gains.

I’m not sure Amtrak goes through Gary, but it stops at Hammond-Whiting, where the view from the train overlooks like an industrial post-apocalypse. That’s the nature of trains — industry and train tracks go together like chips and salsa.

If you were to travel through only northwest Indiana by Amtrak, you’d think the world is made up of industry, utility poles, and casinos. By car, you’d also see billboards for fireworks and adult stores, and countless personal injury and illness attorneys.

On the train, I sleep sporadically. One early morning I woke up to find the train stopped near this structure and garish lighting in Cleveland, Ohio. What could be more representative of industrial eastern America?

Weeds flourish, trees struggle, oily water lies in pools, buildings and train cars rust aggressively, and stuff is strewn everywhere. Human beings seldom appear, although parked cars indicate their presence. In black and white, in color, in summer, in winter, the view is bleak.

I’m fascinated by where cemeteries appear — sometimes unexpectedly in the woods or at state parks like the Smith cemetery at Kankakee River State Park, Illinois or the Porter Rea Cemetery at Potato Creek State Park, Indiana. This one is on Mineral Springs Road in Indiana, where I94 passes over the train tracks. I couldn’t tell at the time, but it belongs to Augsburg Church, a Lutheran church in Porter. It’s about two miles from Bailly Homestead and Chellberg Farm, which are part of Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, past most of the worst of the industrial areas.

When I see puffy clouds, an eggshell sky, and verdant trees on a June day in Michigan, I can’t wait to get to my destination to soak it all in.

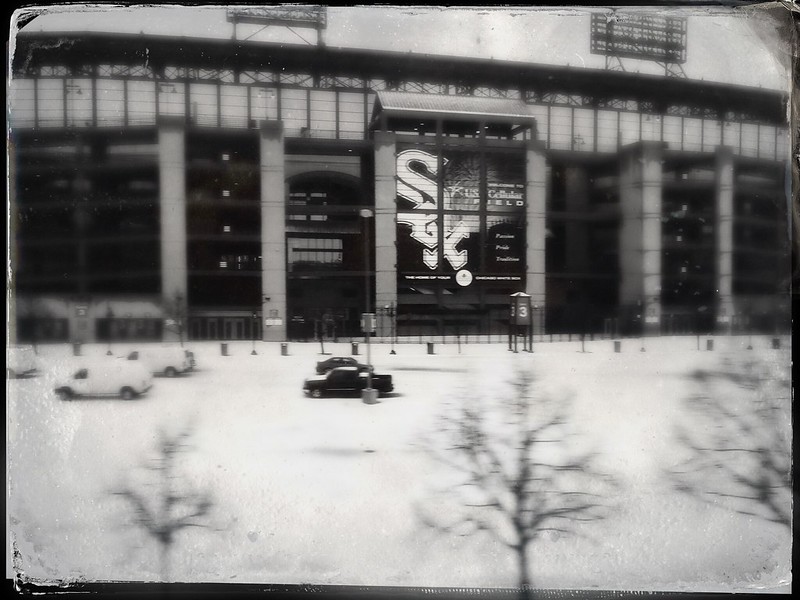

Whether you call it Cellular Field, Guaranteed Rate Field, or Comiskey Park, the home of the White Sox is sometimes a surprise highlight for Amtrak passengers. If you look at the satellite view of the ballpark, though, you won’t believe the number of train tracks to its west. On the starboard side of the train, eastbound Amtrak passengers can enjoy the view of Universal Granite and Marble.

Apparently a scrapyard in Michigan City, Indiana, has mastered Monty Python’s art of “putting things on top of other things.”

I couldn’t figure out the purpose of this attractive building with cupola, but was surprised to realize later it’s in Michigan City, Indiana, not far from the Old Lighthouse Museum. The Hoosier Slide mentioned above was across from the lighthouse on Trail Creek where it empties into Lake Michigan, near this building. That would have been something to see from an Amtrak train. Now the Hoosier slide site is covered by a NIPSCO coal-fired plant. Progress. Rest in peace, Hoosier Slide. May we not forgot what we have lost and never known.

This wavy fence in Michigan City, Indiana, baffled me. I’ve seen them elsewhere, I think, but I don’t know the purpose other than aesthetic.

There may be millions of nondescript, decaying buildings across the U.S., but I haven’t spotted many more nondescript than this one.

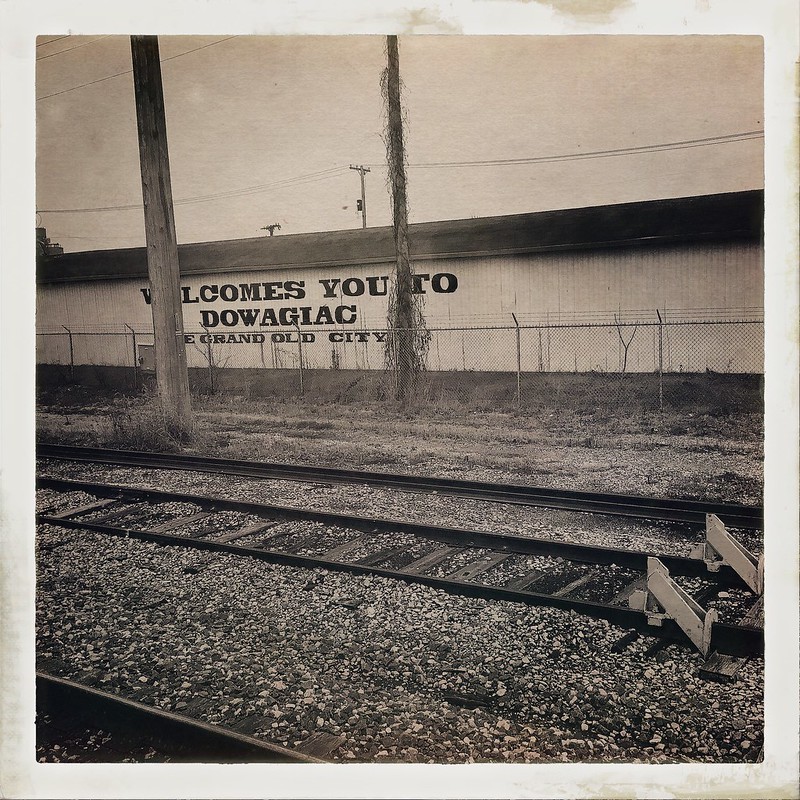

The appearance of this building belies its message that Dowagiac, Michigan, is the “Grand Old City.”

I noticed this long red building on the edge of a small stand of trees in Parma, Michigan, east of Battle Creek. In the satellite view, a dirt road from another building, likely a house, is the only access to it. I’m intrigued by the tall chimney.

With no immediate neighbors, this house, likely part of a tree farm, looks lonelier than it is.

Farm buildings dot the back roads, and rails, of middle America.

Some houses in Pennsylvania towns like Johnstown are spaced closely together, with nearly touching side walls or an alley almost too narrow to squeeze through.

These houses on a hill are farther apart. I wonder if they would have been high enough to escape the Great Flood of 1889—or any since. The area’s geography makes it prone to flooding even without breaking dams.

Johnstown, too, has nondescript commercial buildings.

Some Amtrak stations, like the modern monstrosity in Ann Arbor, are cold and utilitarian. Next door, Ann Arbor’s former station has been converted into an upscale restaurant, Gandy Dancer.

Old school stations remain in use in Michigan and Indiana.

Often there’s not much to see in the dark, but I spotted the same rotting cars from the EB Capitol Limited. Nearby I found a National New York Central Railroad Museum. If they’re intended to be exhibits, they may use a little work.

The morning Dan Ryan Expressway from Amtrak.

This is what you, and New Buffalo, Michigan, look like to an Amtrak passenger.

As children, we liked to watch for the caboose at the end of long freight trains. When the news pronounced the demise of the caboose, I was distraught. When I can, I watch the scenery recede from the last car of the Pennsylvanian, unimpeded by a caboose, remembering the miles of track and the cities, towns, stations, farms, taverns, fields, rivers, creeks, houses, plants, and stores behind me — and ahead of me on the return.

Finally, all journeys must have an end. Mine passes over the Calumet River through Chicago’s steel history.

Crossing the Calumet River on an Amtrak train passing through the former South Works steel region. Chicago Skyway in the background.

Right now, all over the world, a nearly infinite number of things are happening. Hawks pursue rabbits; factions make war; dust filters through the atmosphere; buildings burn; stars shine; children die. Things happen, and everything changes. No one can comprehend it all, only what we experience. Our limitations are our protection; in omniscience lies madness.

My thoughts rambled on during the train trip from Chicago to Ann Arbor. In my limited view from one of the train’s windows, it was a perfect, sunny mid-September day, and in the back of my mind I was looking forward to a weekend spent with friends. I gazed out the window, unable to focus on reading or the other usual train pursuits.

The Amtrak passenger train braked more suddenly than usual, throwing everyone slightly forward. It seemed a strange place to stop, in the middle of a crossing in Albion, Michigan. Sometimes passenger trains halt to allow their freight brethren to pass, but generally the delay takes place out of the way and doesn’t interfere with auto traffic. To me, sitting in the second car, just on the crossing, this stop felt different.

It was.

A couple in an auto waiting at the crossing got out and walked toward the train. I wondered why.

At first, the passengers continued their pursuits — chatting, reading, listening to music through earphones, eating, drinking, or staring out the window, perhaps thinking of what the end of the trip held — reunion with family, school, work. At last, however, the low buzz of activity and conversation heightened as more people noticed how unusually long the train had stopped. A few made joking comments. The uniformed personnel who generally bustle back and forth between the cars had all disappeared. There was no one to ask about the delay.

A rumor from the first car floated back to mine; the train had hit a person in a motorized wheelchair. A motorized wheelchair? What is the likelihood of a motorized wheelchair being in the crossing just when a train is coming? In a small town in Michigan? Then, what is the likelihood that someone would think up that particular scenario?

Someone must have been hit or hurt, or perhaps become seriously ill; a PA announcement requested that any medical professionals on the train make their way to the café car.

The Albion police and two ambulances arrived. The police quickly set up the yellow “Police Line — Do Not Cross” tape around the triangle bordered by the train’s first car and a half and the grassy area next to the crossing, using several convenient trees. Two young women, late ‘teens or early twenties, stood on the grass, hugging each other and crying. The couple from the auto and then the paramedics talked to them and tried uncomfortably to comfort them. I wondered if they had seen the accident, or if they knew the victim well. For a while, they sat on a curb next to the crossing, but at some point they must have left. I wondered if they would seek professional help.

The conductor walked through the train asking that people not open any of the outside doors. “It’s very morbid, believe me,” he said. I knew then that the medical professionals requested earlier were not for the accident victim, but for someone else.

Both ambulances were parked for at least an hour, lights flashing and paramedics walking about, but no one seemed to be doing anything; it all seemed very disorganized and haphazard, almost dreamlike. Finally, both ambulances left, leaving only the police and what were most likely witnesses as well as the invariable spectators. By now, even the couple in the auto had driven off.

For a long time, the police wandered around aimlessly, at least to my inexperienced eyes. One man, sporting long hair and civilian clothes, talked to nearly everyone else, including the police and witnesses, although his role was unclear. He gestured and pointed quite a bit. He remained on the scene during the entire investigation. Other people noticed him as well and wondered who he was.

Meanwhile, the people on the train were becoming impatient. The man across from me spoke of a birthday party in Dearborn he was to attend, schedule for 6 p.m. Two women in front of me were going to two separate wedding showers. When they discovered their purpose in traveling was identical, even though the destinations weren’t, they fell into a deep conversation.

Some of the police began to board my car and walk toward the back, returning to the front and exiting a few minutes later. It occurred to me that they were probably using the lavatory. A crowd had gathered in the foyer between the first and second cars, and the police and conductors had to make their way through them. I didn’t see any reason for the convention, other than to be in the way or to see something of the action. They were a chatty, laughing group.

As the quarter hours, half hours, and hours passed, the passengers became more restless and agitated, wondering how long it would be before the train would be allowed to move on. A very young police officer told our car that the area was considered a “crime scene” and that they could not allow people off the train to contaminate the integrity of the scene. The photographers and others still needed to do their work. They were working as quickly as they could, he said, but could not make any promises about when the train would be released. I wondered what the “crime” was.

I overheard that we were waiting for another engineer to arrive; the train’s engineer was too traumatized to continue. I wasn’t surprised. I’d read before that train engineers involved in accidents suffered trauma long afterwards. Imagine seeing that you are about to hit someone and that that person is about to die. This probably has happened to many an auto driver, but without the surety of death, nor the particularly grisly qualities of a collision between train and human. Most likely only an engineer who has experienced that sickening moment fully understands the trauma and its reasons.

The passengers I heard talking didn’t say much about the victim or the circumstances. Most felt primarily inconvenienced and talked about why with people nearby. Some complained that no one from either Amtrak or the police was providing us with necessary information about when the trip was to resume. There was a rush toward the train’s only phone; one person came back and said offhandedly to anyone listening, “Don’t even think of trying to get to the phone.” “There a line?” one man asked. “Is there ever!”

Outside, the sun continued to create the perfect day. I looked out the window, forward, and for the first time noticed a motorized wheelchair. The police must have put it there within the last half hour. Next to it lay something covered in white. I must have reacted; the man across from me asked me if I’d seen something. “No, not really,” I answered. I didn’t want him or anyone else to talk about what lay under the white. I tried not to look at it, but it was directly in my line of my vision. I saw it and thought, “Only a couple of hours ago, that was a person, maybe going somewhere, just like I am, just like we all are. No more. Just lying there, an object for investigation.”

The police walked around the wheelchair and the body. A photographer appeared and took several photos of the site, including the wheelchair. Another lifted the white material as well — from the other side — and snapped several shots from several angles. The majority of people on the train were unaware of the grisly proceedings.

The man across from me opened a plastic bottle of diet soda. I was thirsty, too, but it seemed disrespectful to satisfy that living desire in the presence of recent death.

On the corner parallel to the train and the crossing, a small herd of boys on bicycles gathered. Each stood poised over his bicycle’s seat, watching the proceedings. It must have been at least 3:30 or 4:30 by then. School was out.

Another police officer boarded the train. He quietly asked the first few people some questions and seemed to disbelieve their answers. He looked around and asked loudly and a little plaintively, “Didn’t anyone see anything?,” as though he couldn’t believe what he had heard. The passengers looked at each other in puzzlement. How could people sitting in the second car be expected to see what must have happened at the front of the train? A young policewoman joined him; they asked each passenger for his or her name, date of birth, address, and phone number, as well as if he or she had seen anything and how fast the train was going at the time of the accident. This last question seemed pointless to me. A train’s speed is very deceptive; usually they are traveling much faster than it feels to the passengers. I suspect the answers ranged from five mph to 70 mph — all subjective guesses and not very reliable in determining exactly what happened. My own estimate was 15-20 — but I would not swear to that.

People continued to be increasingly restless. Another rumor began circulating — that the train was going to back up to the last station, which was quite a way back, so the police could get clearer photographs and drawings. The complaints began again. “I’ve got a better idea — why don’t we move forward?” Not too long after, the train started backing up, and several passengers began groaning. I watched the wheelchair and the white-covered mass recede before me.

The train did not back up to the last station, but just far enough to be out of the way of the police and probably most of the crossings. The passengers became louder as more and more talked to each other. A series of conversations unrelated to the accident arose as people found out where their neighbors were from, where they were traveling to, and why. The little mob in the front of the car continued to banter and laugh. I kept thinking of the shape lying a few blocks ahead.

Eventually, the engineer arrived, and the police cleared the train to leave. From Albion to Ann Arbor was a fast, uneventful journey; I arrived at 6, about four or five hours late. By then, the day’s bright sunlight was muted with the oncoming night. Later, my friends took me to dinner and then to a nostalgic toy store. Even then, I couldn’t help thinking of the white-covered figure and what it might have been doing had it not been for bad timing — or, perhaps, from its perspective, the timing had been perfect. And how it would never see another bright mid-September day. I thought such thoughts until they became too painful, too overwhelming. I could not think them for the millions of others who died that day. I cannot think them now.

1998

Copyright © Diane L. Schirf

I’m on the Pennsylvanian. As a result of being among the last one-third to board, I found myself next to a young woman who is one of those nervous, self-centered pieces of work you don’t want to find yourself next to. The train was clearly going to be full; by the time I got on, there were few empty seats left. She had all her bags piled onto the seat next to her and had settled in comfortably with earbuds in when I disturbed her peace by rudely tapping her to get her attention when she missed my initial hail.

“WHAT?” she exclaimed.

“Is anyone sitting here?” I repeated.

Instead of replying, she huffed and sighed heavily, collected her bags, and flung them disgustedly onto the upper rack across the way. Clearly, she had expected to have the only empty seat on the train to herself. Meanwhile, I smiled beatifically at the people in the line behind me, who of course were waiting for her and me to get out of their way so they could find seats, too. I had spared them from my newly discovered Center of the Universe.

I took my coat off and sat on it. Apparently, a cord must have been nearly touching her through her layered clothing, akin to the pea bothering the princess through many mattresses, because she abruptly suggested that, if I weren’t going to actually wear it, I put it overhead. “It’s . . .” within an inch of her person!

When the conductor came through to collect tickets, she seemed taken by surprise. As she rummaged frantically through her bag searching for tickets and ID, she jabbed me a dozen times or more with her flailing elbow, which, oddly, didn’t bother her given her sensitivity to touch and wasn’t supposed to bother me. Later, as she read and tossing her hair, it was all I could do not to say to her in the same nervously fussy tone she’d used on me, “Would you mind not shaking your head like that? Your dandruff and vermin are, like, you know . . .” Eventually, after I’d dozed off, she woke me up to trounce off somewhere, which gave me the opportunity to plug in my iPhone, which gave her the opportunity to harumph when she demanded her seat back. After that, I left her with her space and mine all to herself.

My Christmas wish for her: The maturity and the wisdom to understand that she is no more significant than the 7 billion other humans with whom she shares Planet Earth. And the few dozen with whom she shares an Amtrak car.

I’m not holding my breath.