We’ve had the eastern tiger swallowtail. Here’s a female black swallowtail, equally colorful in her own way.

Here’s video of a persistent male.

We’ve had the eastern tiger swallowtail. Here’s a female black swallowtail, equally colorful in her own way.

Here’s video of a persistent male.

Having survived an autumn visit to Camp Bullfrog Lake, and being fond of the Palos area for its hills, moraines, sloughs, woods, and forest preserves, I wanted to plan another stay. There are only two large cabins, and I was happy to get one of them for May, which I had figured would be at the height of fine spring weather. HA.

The adventure began in Homewood, where I met J. He was immediately distracted by an Operation Lifesaver “train” blowing its horn as it circled downtown Homewood. It looked popular and crowded, or we might have ended up angling for a ride.

Our first stop was at Cottage on Dixie, where, unbeknownst to us, we were about to have our last meal there. A month later the owner announced it was closing. A few days after that, the owner announced a grand reopening on July 18. My head spins, and I’m guessing it wasn’t the last Cottage meal after all.

We settled in briefly at Camp Bullfrog Lake, then set out for sandwiches at Ashbary House at the Old Willow Shopping Center, set against a wooded hillside. I love the way it looks.

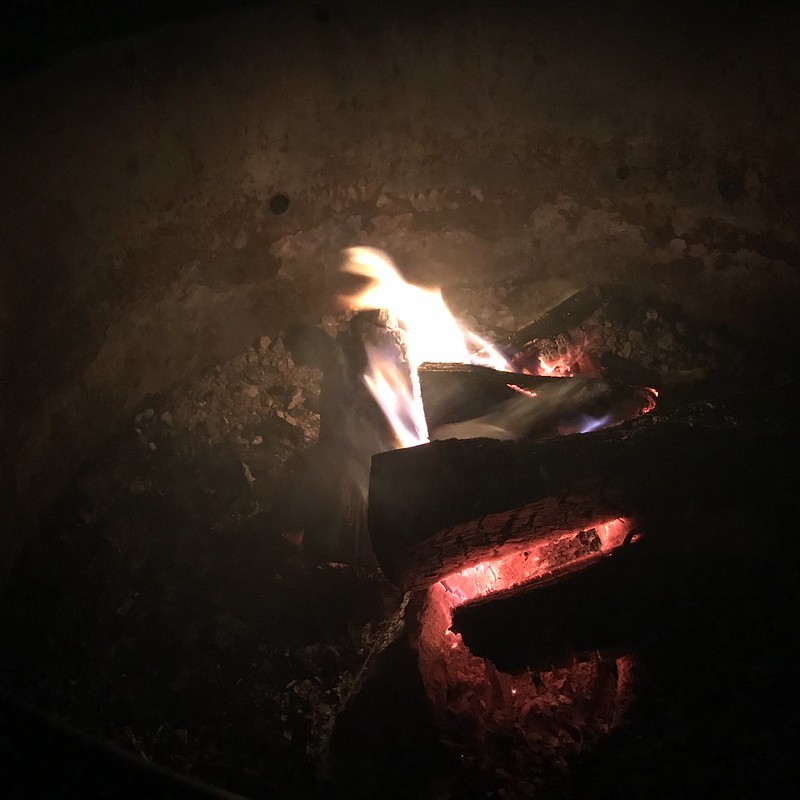

Back at camp, a full moon (well, a few hours past) rose above the lake into the clouds, looking a bit like Saturn. The clouds and moon over the lake were the perfect complement to the campfire. Our fire-starting skills are better if still in need of improvement. A bucket of topnotch fire starter didn’t hurt, and with close nursing our fire flamed merrily for several hours and marshmallows. The full moon was an unexpected bonus. (Usually I pay closer attention to moon phases.)

The morning looked promising weather wise.

I found we had a lot of neighbors at the next cabin, with breakfast piled high atop their picnic table. One of their cars had Alaska plates. I marveled that anyone would drive from anywhere in Alaska to Illinois. I might never have gotten past, say, Montana or Wyoming.

After breakfast at Maple-N-Jams, we happened upon the Nut House in Bridgeview. I gained weight looking at the colorful displays, but managed to walk away with mostly seeds.

Upon returning to camp, we found the perfect excuse to skim old travel magazines and, in my case, read more about The Black Death — a lengthy downpour. Undoubtedly payback for the serendipity of the full moon.

With numerous sloughs and the Des Plaines River, Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal, and Cal-Sag Channel running parallel to each other through this area, there are plenty of steel truss bridges. I love them. I wonder if the blue paint on some is relatively new to dress them up.

I thought we might see a lot of flowers in bloom at Little Red Schoolhouse, but maybe mid to late May was too late. Instead we found one of the ponds full of tadpoles, two northern water snakes, and a green heron trying to be still and invisible. Suddenly, it took off after another green heron we hadn’t noticed across the way. A brief yet epic battle ensued, and in the end I couldn’t tell which one hightailed it to the woods and which took over pond patrol.

On the other side, the great blue herons and great egrets of Longjohn Slough kept a watchful eye on each other, like boxers in their respective corners between rounds.

At Little Red Schoolhouse we’d seen a flier for a mushroom/fungus walk at Swallow Cliff Woods. We decided to investigate on our own. We didn’t get far down the trail before my pain levels rose and my energy levels flagged, just far enough to this tantalizing pathway. Someday.

I hadn’t noticed any mushrooms in the short distance we’d walked, but on the return trip we both noticed several (not the same ones in all cases). J is credited with the find of the day, a magnificent morel. I don’t think I’ve seen one “in the wild.” I began to understand why the naturalists had chosen Swallow Cliff Woods for their fungus walk. Now if only I could find (or recognize) slime molds in any form . . .

For dinner we headed to Jen’s Guesthouse, formerly Courtright’s. It was too wet to sit outside in the garden area against the wooded hillside, but the inside isn’t shabby.

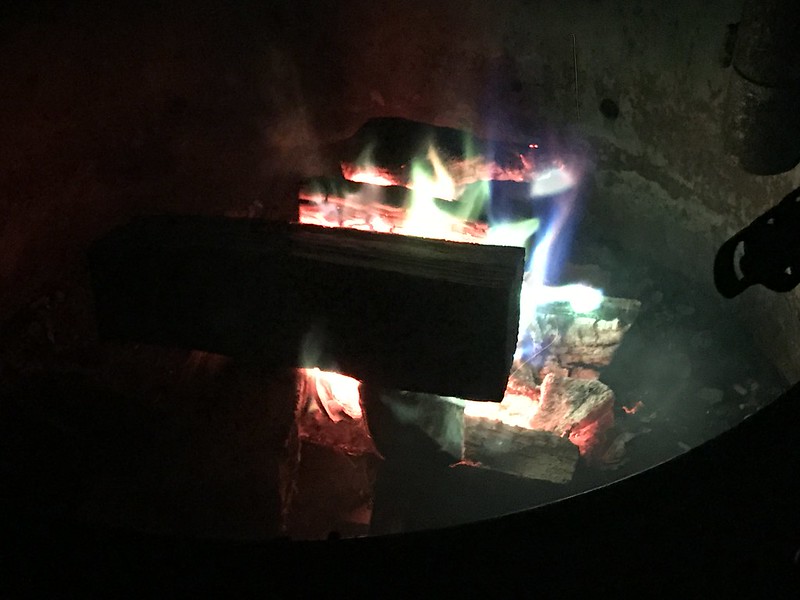

Back at camp, we still hadn’t perfected the art of fire making but finally had enough going to toast marshmallows. When we were sure we’d had enough, we tossed in the Mystical Fire. I found out later we should have used three packs, but even one was . . . mystical. Or at least colorful.

We went to Lotus Cafe, which turned out to be part of Pete’s Fresh Market, and ended up with a breakfast-by-weight buffet. We also stopped at Strange Brew Cafe, which I recognized from last year.

Back at Camp Bullfrog Lake, we packed and took a last walk around. When I approached the pier, I was startled by a great blue heron perched on the railing, no doubt keeping an eye out for fresh lake fish (or even the eponymous bullfrogs). Just when I thought it was going to let me get close, it slowly flapped off to shore. They like to keep their distance. I don’t blame them.

While driving around we kept passing a historical marker sign and decided to investigate. This led us to St. James at Sag Bridge Church and Cemetery, which involved some steep hills. I can’t say for certain we found the historical marker, but i did spend a few moments checking out Our Lady of the Forest. It turns out the church is on the National Register of Historic Places. I’m reminded too that I want to read The Mystery at Sag Bridge by local writer Pat Camalliere, whom I’d met briefly at Settlers’ Day at Sand Ridge Nature Center in South Holland.

Despite the I-355 extension and the encroaching warehouse-type developments, I’m still charmed by most of Bluff Road in Lemont. We stopped at Black Partridge Woods, walked along the picnic shelter side of the stream for a bit, then returned to the parking lot to find two male scarlet tanagers paying court — presumably — to a female. I don’t get to see these birds very often, so it was a treat and a thrill worth the entire trip — downpours, damp, and all.

We made another visit to Little Red Schoolhouse Nature Center. While no green heron lurked about that I could see, the great blue herons and great egrets were still skirmishing along Longjohn Slough.

For a light dinner we stopped at Spring Forest 2, where I love the terraced outdoor seating areas.

Finally for dessert, we headed to the Plush House to enjoy ice cream from the comfort of an Adirondack chair. And so ended another weekend adventure in one of Illinois’ more interesting areas.

Indian Ridge Marsh is a recent (2017) addition to the Chicago Park District, located a little southeast of Big Marsh Park near Lake Calumet. Norfolk Southern lines run down the ridge. While I was visiting, NB and SB freights met and passed each other.

Motion parallax is obvious here once you get past the trees and keep your eye on the power towers, which hardly seem to move, yet disappear.

Lightt was a short-lived video app I still miss. I didn’t have time to master it but I liked some of its effects. This video and a few others demonstrate motion parallax, which I had to look up after I noticed it.

December 27, 2017: After seeking elk in the outlying areas of Benezette, we found a little herd at the campgrounds in town, which they favor. I handed my phone off to my cousin, who was in a better position to capture them. Benezette is part of the area that’s been rebranded “Pennsylvania Wilds” to attract adventurous tourists of the have kayak, will travel variety.

It got colder this morning before it got warmer. The sea smoke was curling and eddying in interesting ways.

As a child, I didn’t think about water until I started visiting a friend whose family drank well water that smelled and tasted of sulfur. The odor permeated their house. “You get used to it,” she said. Accustomed to the tasteless taste of “city water,” invariably I felt thirsty the moment I arrived. I never got used to it.

Forty-five years ago the typical person didn’t carry a water bottle or buy bottled water. We drank whatever came out of the tap. Unswayed by Dr. Strangelove or decades of bottled water marketing, I still do, and that’s what I fill my insulated water bottles with when traveling.

On our annual pilgrimage to Pennsylvania in the 1960s and early 1970s, we used to stop at a couple of roadside springs and fill a jug or two with spring water. We didn’t need to. Our “city water” in New York was fine with us — well, as fine as any water in our polluted world can be. There didn’t seem to be any objection to our hosts’ water, either. By the time I was sentient, we were no longer staying with anyone who lacked indoor plumbing. My guess is my parents liked the idea of getting water from a roadside spring and preferred it as a rare treat. I did too. Water straight from a spring — as nature intended. (We didn’t boil it, either.)

Later we stopped at the usual places and found signs indicating the water was too contaminated to drink — the effects of coal mining. My heart broke a bit at the loss of a tradition and the sense the earth itself was dying one roadside spring at a time. After all, I was being raised in the era of the fiery Cuyahoga River, algae-choked Lake Erie, and the horrors of Love Canal.

I wish I could remember where those springs were and find out if anything has changed.

According to findaspring.com, which seems to be defunct, Pennsylvania leads the U.S. in the number of listed springs with 84. New York is second with 59, while Illinois lags behind with only 17 shown.

When I was visiting my cousin for Christmas 2018, I found out they’ve taken to collecting and drinking spring water. My cousin hinted, however, that the spring is far from picturesque. In my mind’s eye, I saw an ugly, chipped-up plastic pipe protruding from an ugly, denuded hillside in town. Something like that.

The spring is south of Tyrone, so we used a visit to Village Pantry as an excuse to get some water. It’s on a lightly traveled road paralleled by a stream, Elk Run, that seems to cross back and forth under it in several places.

My cousin and his wife quickly set up an efficient two-person jug-passing and -filling operation while I meandered back and forth across the road, drinking in (so to speak) the sights and sounds of the spring and Elk Run on its journey.

When a house buyer sees a stream, he pictures flooding, damage, and dollars. I picture myself at a church picnic at Chestnut Ridge, a lifetime ago, walking on 18-Mile Creek, listening to its gushing and trickling, soaking in the sight of countless tiny drops, waterfalls, and eddies, and hoping to spot tadpoles, frogs, minnows, and fish in the clear water reflecting a perfect summer sun filtered on the edges by healthy trees. I had no way of knowing how ephemeral that experience would be.

Memories.

I don’t know how clean or safe the water from this spring is. As I said, it’s south of Tyrone, whose paper mills wafted their distinctive odor through my aunt’s screen door seven or eight miles away in Bellwood. I’ve seen a discussion about agricultural runoff in the area as well, although many think it’s insignificant.

Elk Run appears to be a tributary of the Little Juniata River. I once told my dad I’d seen a leopard frog in the Little Juniata as it runs past Logan Valley Cemetery in Bellwood. He made a wry comment about it, perhaps “How many legs did it have?” Now he and my mother are buried in Logan Valley. Cemetery, within earshot of the Little Juniata. Water, however clean it is or is not, connects us — all of us. We shouldn’t forget that.

Curious about the current state of the Little Juniata, given I’d been handed two bottles of spring water, I found out it’s not as bad as I thought.

Well, the Little Juniata River is not well-known nationally, primarily because it’s only been a trout stream since around 1975. The reason being that prior to that it was literally an open sewer.

Bill Anderson, president of the Little Juniata River Association

After decades of pollution and a “mysterious pollution event in 1997,” we have brown trout fishers to thank for cleaning up the Little Juniata and shoring up its eroding banks.

We want to make sure this resource stays open for our children and grandchildren.

Bill Anderson

This would have made Dad happy. And he didn’t fish.