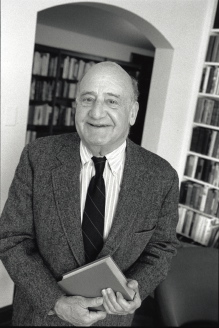

Wayne C. Booth and Ned Rosenheim

I was privileged to have had both Wayne Booth and Ned Rosenheim as professors. Unfortunately, I was too young but mostly too ignorant, too out of my element, too overwhelmed, too dysfunctional, and too depressed to appreciate and make the most of a truly once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. I remember both of them fondly and regret that I did not learn as much as I could from them because I wasn’t ready.

Mr. Booth taught my first-year humanities course. I struggled less with than with courses in other disciplines, like social science, but I still struggled — through Plato and Aristotle, among others. Even then, I read slowly and tired easily, and had difficulty following ideas that were presented in any kind of complex or wordy fashion. I had problems with philosophers in general because so many seemed to present their personal perceptions as fact, which made no sense to me, and to meander on with no useful point in sight. (Although I don’t like structure and objectives, I require them from my reading, oddly enough.)

Something I’d read in Plato made me ask a theoretical question about a man on an island and civilization. It was perhaps the first and only time I had a basic insight into the purpose of philosophy. Mr. Booth liked the question and posed it to the class. He explored it and found the flaws in it. He made a great effort to get me to talk more, to pull me out of myself. He seemed to think that I had something to say, and he even said once or twice that I had potential — I assume he meant potential to be a thinker. Once, someone sitting next to me in the class was bothering me. Mr. Booth caught us whispering and genuinely believed I had something significant to share with the class. I insisted I didn’t, and we moved on. It was an embarrassing and humiliating moment, not because I’d been caught being disruptive, but because I felt I’d revealed my true, foolish, unworthy self to someone who had shown confidence in me and who had encouraged me to be something I knew I couldn’t be. After that, I felt I’d lost his respect. That could have just been the remnants of adolescent angst rather than the reality; I’ll never know. I may have lost some of my own.

Mr. Booth had a gentle sense of humor. In our class, there was a student from Jamaica named Geoffrey (the “correct spelling,” he insisted). One morning a nasty snowstorm hit Chicago. Geoffrey did not appear for class. The rest of us were excited about the storm; it was one of those where big, puffy, distinct flakes fell thickly. Mr. Booth said, “Does anyone want to bet that Geoffrey can’t make it in through the snow?” We laughed. Geoffrey did arrive for the last five to ten minutes of the class, covered with snow and saying, “Wow! Brrr!”

We liked Mr. Booth and our class so much that, at the end of it, we held a party. I think he and his wife played a duet for us. I do remember a lovely evening and a sense of sadness that something wonderful was over, like the feeling actors have at the end-of-run cast party. An experience had ended that could never be repeated — an experience I’d had, yet not had.

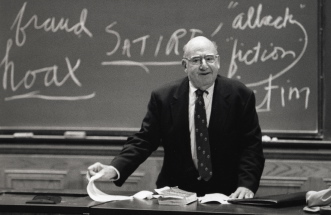

The class I had with Ned Rosenheim was perhaps two to three times larger — at first. The subject was “Fiction of the 1930s,” which Mr. Rosenheim claimed he was uniquely qualified to teach at the University of Chicago because “I read all these books when they were bestsellers.” He made a lot of humorous, self-deprecating comments about his age. He was a few months older than my mother.

“Fiction of the 1930s” was a popular class, one that students slept out for, but I didn’t have to because English language and literature majors had priority. The classroom was crowded the first day, almost like a chemistry lecture class. I remember Mr. Rosenheim making jokes about the size of the class and wish I could recall what they were; I think he said something about people being in the wrong place because it was not a popular class. He tried to convince us it would be a difficult one, noting chemistry and physics majors began by thinking English and other humanities classes were quite easy compared to, say, organic chemistry. Indeed, I found that was the consensus of the class.

Within a few weeks, the class had shrunk dramatically. I couldn’t tell you why. I don’t know how many papers we had to write, but I suspect part of it was the reading. Reading eight to ten substantial novels like The Late George Apley, The Grapes of Wrath, and Studs Lonigan is not an easy feat, on top of two or three other courses. The holdouts were primarily the humanities majors, which was probably more comfortable for Mr. Rosenheim — that is, teaching people who shared a love of reading rather than those trying to get by easily.

Because of his jovial manner and cherubic appearance, most people seemed to think Mr. Rosenheim would be an easy grader. I picked up either a paper or an exam and had received a high mark and assumed everyone else had as well. I discovered later that there were only a couple of As and Bs, many Cs, and a healthy amount of Ds. To me, that’s how it should be, because if C means average, it should be the most common grade, while there should be very few As (outstanding) in proportion. I found this impressive because it demonstrated to me that one could be a witty, “nice” person, yet still be demanding and tough where it matters. (It didn’t hurt that I had received one of the high marks!)

Dallas was a very popular television show at the time, and I had a silly T-shirt — actually unrelated to the show or the show’s merchandise — that said “Ewing Oil” with a tagline. Mr. Rosenheim noticed it one day and made a comment about it (another that I can’t recall!), then had me stand up and model the shirt for the class, even having me turn around. I wondered if he did it because I was always trying to hide, and that was his way of making me visible. It was another embarrassing moment, although the embarrassment quickly faded into a happy memory.

At the end of the quarter, I was going to be late writing the final paper — so late that Mr. Rosenheim would not be at or returning to his campus office. He gave me his address, a lovely apartment at 58th and Blackstone, and told me I could bring it to him there. It was kind of him to offer me that chance, and he was gracious when he met me (I was nervous).

It seems terrible that I can’t describe these professors’ classes or the discussions in detail, as though I did not get much out of them. At the time, I was too overwhelmed by the entire experience of campus life to take it all in, and I had not adapted very well (and never did). But each did have an impact. Both gave me confidence that I had ability and even potential, at least in the humanities. Mr. Booth made me believe in questioning everything — including Plato and Aristotle, including everything we assume is true because it has always been accepted as such. Mr. Rosenheim helped me appreciate the subtleties of literature, to explore the text and the subtext.

As 18- to 20-year-olds, we no doubt thought Mr. Booth and Mr. Rosenheim ancient, at least 70 if not 80. I did, and in spring of 2001 it occurred to me that they must have already passed on, although I had not heard anything specific. Then I must have seen something about Mr. Booth, because realized that he was not only alive, but still active at the university. I visited the University of Chicago website on the off chance he might have an e-mail address. He did! I wrote to him knowing that there was little likelihood he would write back. He did!

He said he remembered me, although the memory was admittedly “dim,” then suggested that I get together with him and his wife for lunch while they were still in town. He also said that, for some reason, my note had sparked him to pick up The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton. I was stunned by the offer and the comment, which came at a time when I felt overwhelmed by the sudden decline my father’s health was suffering. (He died July 28, 2001.) For whatever reason, Mr. Booth and I never did have lunch or the conversation about what was on our minds, as he put it. Another missed opportunity, another regret.

When I read of Mr. Booth and Mr. Rosenheim’s deaths, I was surprised to learn they were both younger than my father. During all those years I had carried the impression picked up as a youth that they were very old men, and in reality they were only in late middle age and at the pinnacle of their academic careers and intellectual lives. What an odd thing perception is in the young, and how long it lasts.

Thank you, Mr. Booth and Mr. Rosenheim. You influenced so many of us in ways that others, such as politicians and other so-called leaders, can only envy. Thank you for making us think for ourselves, like the natural philosophers we are. And thank you for proving that the discussion and debate of even the most sensitive ideas do not need to be vicious or mean-spirited, and that they can be and are exciting and enlightening.

We’ll miss you and your wisdom. And our lost opportunities.

What a lovely piece. Clearly both wonderful men; I had the pleasure of knowing Ned well, and he is much missed to this day.